The Girls Are Not Alright: Responses to Three Claims that the Youth Mental Health Crisis Is Exaggerated

Why changes in stigma and self-reporting procedures cannot explain the international decline of adolescent girls’ mental health.

Since beginning my series on the international youth mental health crisis, a number of articles, posts, and podcast episodes have surfaced challenging whether there actually is a crisis and/or whether it was caused—in large part—by the rise of the phone-based childhood between 2010 and 2015, as Jon and I argue.1 In previous posts on this Substack, we have shown that rates of anxiety, depression, and self-harm have been rising across all major English-speaking countries and that suicide rates are higher for Gen Z girls in those countries than any previous generation of girls when they were the same age. We have also shown that worsening mental health trends are happening across the five Nordic nations and much of Western Europe. We have also argued that these mental health declines are driven—in large part—by the combination of rising overprotection in the real world and underprotection online. In response to researchers who are skeptical of this theory, Jean Twenge addressed thirteen alternative explanations—including the Global Financial Crisis of 2008—and showed why each of those alternatives was inconsistent with known facts about the timing and nature of the crisis. (See also Jon’s recent response to skeptics who claim that we have “no evidence” of causality, only of correlation.)

However, there are other alternative explanations that still need to be addressed, specifically those based on claims that the mental health crisis is not real, or has been overstated. In this post, I address three of the assertions that would support the “overstated” hypothesis:

The rise in self-harm rates is mostly an artifact of reduced stigma

The rise in self-harm rates is mostly a result of changes in reporting and screening

There is no international rise in teen girls’ suicide rates.

In short, I will argue that there is an international crisis, that a majority of the rise in rates of self-harm cannot be explained by reduced stigma and reporting changes alone, and that the conversation around international suicide rates has been muddied by two datasets that tend to underestimate known rates of teen suicide since 2010. Simply put, this alternative explanation (the “overstated” hypothesis) is unable to adequately explain the international deterioration of youth mental health since the early 2010s.

(Note that Jon and I have been collecting every alternative explanation we can find in an open-source Google Doc – if we are missing any, please add them there. I plan to cover others in future posts. Also, note that I focus primarily on girls and young women in this post because this is where the central debate is happening between social media use and mental health outcomes. For more on boys, see this Substack post).

Challenge #1: The girls are alright: Rates of self-harm are rising primarily because there’s less stigma associated with going to the emergency room.

A common claim made to explain the changes in youth mental health trends—from anxiety to suicidal ideation—is that there is simply less stigma associated with talking about mental health and seeking support. Therefore, it is not possible to differentiate between changes in stigma and changes in actual mental health outcomes. Although Jon and I agree that there has been a reduction in mental health stigma in recent decades, we have pointed out that changes in behavioral outcomes, such as emergency department visits for self-harm and actual suicide, are hard to explain by changes in stigma and self-reports alone.

Some have pointed out that emergency department visits for self-harm may also be influenced by changing norms and willingness to seek help, making these data yet another unreliable gauge for true changes in a population's mental health. However, I believe that rates of hospitalizations can help us distinguish the signal from the noise and more reliably indicate whether the mental health of a population is getting worse.

Being hospitalized is much rarer than visiting the emergency department, and it requires clearance by their medical provider (i.e., kids are not making the choice themselves). Most kids who go to the emergency department are not hospitalized, as hospitalization is reserved for the most severe cases. Hospitalization requires an enormous amount of time, money, and resources (e.g., beds)2 — and for a variety of reasons (e.g., preference for less restrictive care), providers are not particularly inclined to want to hospitalize kids unless necessary. These resource constraints plus a general reticence to hospitalize would mean that even if many of the increases in emergency department visits were a result of reduced stigma and a higher willingness to seek help, this would not explain sudden and rapid changes in actual hospitalizations. (Unless one is to argue that thousands of preteen girls in many countries with severe symptoms were not going to the emergency room in 2008, and then suddenly started to go in the early 2010s because of a sudden reduction in stigma).

Using CDC nonfatal self-harm data from 2001-2021, we can zoom in on trends among adolescents who first go to the emergency department and are subsequently hospitalized. The data reveals a clear story: Since 2007-08, there has been a 518% increase in hospitalizations for 10-14-year-old girls. (The rates for 10-14-year-old boys were unavailable).

Figure 1. Hospitalization for intentional self-harm has risen by 518% since 2007-08 among U.S. 10-14 year-old girls. Note that there are some missing data years, including 2009-2012 and 2018-19 for hospitalizations. Also, note that boys are not included as their rates are so low. (Source: CDC Non-Fatal Injury Reports.).

The data for 15-19-year-old girls also shows a large rise, as you can see in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Hospitalization for intentional self-harm has risen by 91% since 2007-09 among U.S. 15-19 year-old girls. Source: CDC Non-Fatal Injury Reports. (Spreadsheet).

So, while the initial reason adolescent girls are showing up at the ED at higher rates could plausibly be related to decreased stigma, it does not explain why they would be actually admitted more often unless they were, in fact, actually experiencing severe symptoms. In fact, this 518% increase in hospital admissions for younger teen girls is the largest increase I have seen in all of the hundreds of datasets I have graphed.

One last note on this: it is not clear why we would see rises in emergency department visits and self-harm hospitalizations all across the Anglosphere at the same time and concentrated among the same group of people (adolescent girls) and not other age groups if this was mostly a result of destigmatization. Could destigmatization have happened in so many countries simultaneously and so rapidly?

Challenge #2: The girls are alright: The rise in self-harm is a result of changing diagnostic criteria and screening.

A second challenge that has emerged in recent months came from an important article by the economists Adrianna Corredor-Williams and Janet Currie at the National Bureau of Economic Research, arguing that a substantial amount of the rise in reported self-harm episodes among adolescent girls over the last decade may be explained by a variety of changes in the way that these episodes are screened and reported by doctors and clinicians.

Specifically, Corredor-Williams and Currie point to a series of changes in psychiatric healthcare between 2010 and 2015:

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act was passed, spurring many healthcare reforms from increased mental health coverage for young adults (18-26) to mandating insurance companies to cover yearly screenings for depression among adolescents and requiring the Health and Human Services to develop new guidelines for preventive services for women (which led to recommendations for girls ages 12 and older to be screen annually for depression).

In 2013, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders (aka the DSM-5) was released. This new version updated the definitions of anxiety and depression, such as including bereavement as a form of depression and merging dysthymic disorder (low-level but chronic depression) and major depressive disorder into a new category of persistent depressive disorder. The criteria for anxiety disorders were also refined, aiming for more precise diagnostic specifications. (But note that these changes do not have any clear connection to changes in rates of hospitalizations for non-fatal self-harm).

In 2015, the International Classification of Diseases (aka the ICD) was updated from the ICD-9 to ICD-10. This change had impacts on coding for self-harming and suicide-related behaviors. In the ICD-9, providers had to enter two codes to indicate self-harm (one being the type of injury and one being its intent). The ICD-10 only required providers to include one code for self-harm. The ICD-10 also introduced a new system of notes that was designed to make coding more precise. Specifically, it encouraged providers to include a second code to a primary mental health code. For example, in the ICD-9, if someone is coded primarily with “depression,” they may not also be coded with “suicidal ideation” as these two often overlap. In the ICD-10, it was encouraged to put both codes in. This change may have inflated the number of additional diagnoses.

Taken together, the authors argue that these changes can help explain some of the rise in mental health problems and demonstrate how this appears to be the case for self-harm episodes in New Jersey hospitals.

These are important factors to consider, and I don’t doubt that such changes had an impact on reporting and rates in the U.S. But to what extent? Can they explain why youth mental health rates changed so rapidly around the United States in a way that so closely aligns with international trends? I believe that they cannot, as I have found four important contradictions that go against what we can call the “changing diagnostic hypothesis.”

Contradiction #1: The changing diagnostics hypothesis predicts that the big rise in self-harm hospitalizations should happen after 2015, but in fact, it happened much earlier.

As you saw in Figures 1 and 2 above, the rise in hospitalizations for self-harm began before 2015, around 2010 (long before the ICD change).

In fact, the average estimated yearly increase of adolescent girls (ages 10-19) admitted to hospitals from 2010 to 2015 (2,224 girls per year) was larger than it was from 2016 to 2020 (an additional 614 girls per year).

Other major studies on inpatient psychiatric ED and hospitalization trends confirm these post-2009 increases among adolescent girls.

Contradiction #2: The changing diagnostic hypothesis predicts that we should see changes across all age groups, but in fact, we only see increases among adolescent girls.

If the sudden sharp rise in rates of self-harm were caused by a sudden change in diagnostic criteria, then we would see sudden rises for all age groups and for males and females. But this is not what we see (as Figure 3 shows). In fact, among women, the only age group showing a substantial rise is girls ages 10-19.3 Hospitalizations among women above the age of 30 have actually been declining since 2010.

Figure 3. Hospitalizations for non-fatal self-harm episodes among women (ages 10-59). Source: CDC Non-Fatal Injury Reports. (Spreadsheet).

(Note: We see these same sex by age-based patterns in Australia. This is the one additional Anglo country I have specific hospitalization data that looks across age groups.)

Contradiction #3: The changing diagnostics hypothesis predicts that all countries will see a rise after the 2015 change in the ICD, but changes before then will be scattered and not coordinated. But—in reality—rates have been rising consistently and coordinated across all five of the major Anglosphere nations since the early 2010

Figure 4 shows the coordinated international rise in self-harm episodes among adolescent girls since the early 2010s.

Adolescent Self-harm Episodes in Five Anglo Nations

Figure 4. Since 2010, rates of self-harm episodes have increased for adolescents in the Anglosphere countries, especially for girls. For data on all sources and larger versions of the graphs, see Rausch and Haidt (2023). Before 2010, not much happened. By 2015, self-harm episodes were at record-high levels in all five countries. (Data for Canada is limited to Ontario province, which contains nearly 40% of the population of Canada.)

It’s important to note that the rise between 2009 and 2015 in Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand cannot be explained by uniquely American trends, such as the ACA or American-based changes in mental health screening procedures. This matters because the consistent international pattern of increasing self-harm rates among adolescent girls since the early 2010s (and not older adults)4 puts in doubt the claim that the American rise in self-harm is primarily explained by those changes as well.5

(See footnote for 6 contradiction #4, which discusses changes in primary and secondary coding. In short, the data from the early 2010s indicate an increase in hospital admissions for children where the primary reason is suicidality and self-harm. This suggests that the observed increase in admissions cannot be solely attributed to an increase in recording these issues as secondary diagnoses.)6

Taking all of the contradictions together, it is clear that in the United States, the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, more adolescent girls are going to the emergency department for self-harm episodes and/or being hospitalized for self-harming behavior. The international pattern cannot be explained by American changes in insurance policies or screening, nor can it be explained by changes in the DSM (which were related to anxiety and depression) or the shift from ICD-9 to 10 because all of this started before the ICD-10 came into effect.

Challenge #3: Suicide rates among teen girls are not rising in most developed countries.

A third claim I often hear is that while teen suicide rates have been rising in the U.S. since 2010, they are not rising in many other countries around the world. I have addressed this argument in previous posts, showing that the rises in poor mental health (including suicide) are missed when we combine everyone and everything together in our analyses.

Specifically, I show that when we combine trends for girls and boys together (or teens and adults), it often hides the fact that suicide rates have been rising for teen girls (see my post on Gen Z girls’ rising suicide rates across the Anglosphere).

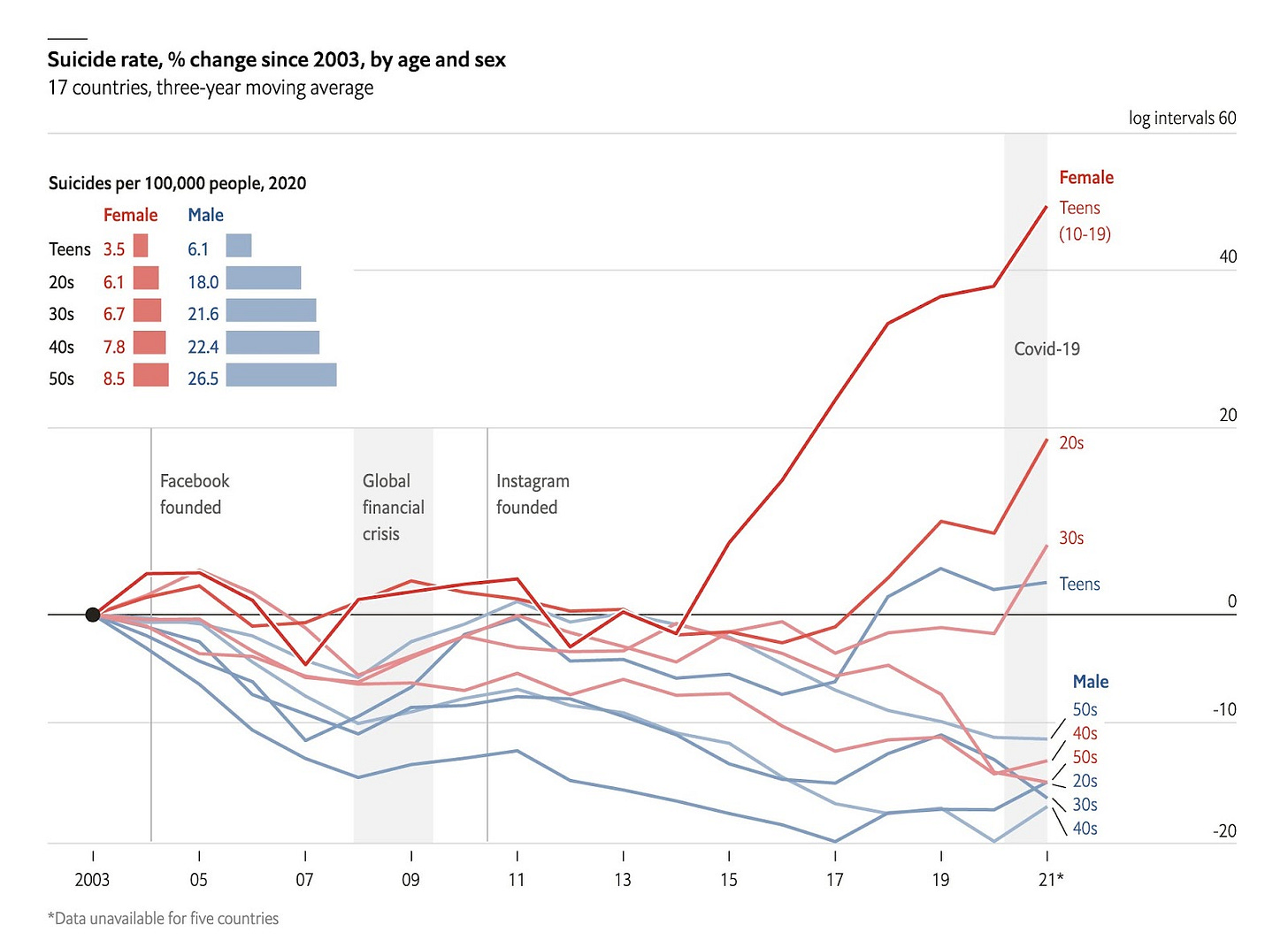

Figure 5, produced by The Economist, is a good illustration of this pattern. Across 17 nations, we see a clear overall trend toward declining suicide rates, for males and for females, with one big exception: females in their teens. There’s also a smaller exception: females in their 20s. When graphs merge all ages together, or merge both sexes together, the large change in suicide for girls and young women is masked.

Figure 5. Percent changes in suicide rates in 17 nations. Source: The Economist. (The data comes from the national statistical authorities and health agencies of: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, England & Wales, Estonia, France, Germany, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Slovenia, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States).

In my previous posts, I also show that when we combine all countries together, it hides the fact that suicide rates have been rising in more wealthy, secular, and individualistic countries, which includes, especially, the historically Protestant countries. In this post, I want to address just one aspect of the international suicide debate: the datasets that are being used. One of the reasons for disagreement among researchers is that we are relying on different datasets to look at international trends in suicide rates. I have found that two frequently used datasets are underestimating known rates of youth suicide from government death registries. I covered one of those—the Global Burden of Disease Study—in a previous post. But the second, the WHO Global Health Estimates also fails to present accurate suicide rate data in countries where we have high-quality death registration data.

Figure 6 shows youth suicide rates in the USA according to three different sources. The most reliable is the CDC, shown in green, which compiles actual numbers of suicides per year, while the WHO GHE (in red) and the GBD (in orange) are estimates of youth suicide. As you can see in Figure 6, both the WHO Global Health Estimates and the Global Burden of Disease Study underestimate the actual changes in youth suicide rates since 2010.

Figure 6. Comparing youth suicide rates between the Global Burden of Disease Study (which estimate suicide rates), the WHO Global Health Estimates (which estimate suicide rates), and CDC suicide rates (which are based on actual reported cases). (Spreadsheet).

In fact, I have been in touch with researchers at Our World in Data (which often relies on both the GBD and WHO GHE estimates) to try and address this issue. After an initial inquiry into the discrepancies, they reported back to me that:

For countries with high-quality death registration, including the U.S., the WHO GHE methodology says that it uses the most recent vital registration (VR) data, which should be the same as the WHO MDB data [WHO Mortality Database].7 However, they seem to be lower across countries that I explored — United States, United Kingdom, Canada, France, etc. — in the most recent years. [bolding added by Zach]

[NOTE: Our World in Data just addressed this issue by publishing the WHO MDB data on Tuesday, which now allows us to compare countries with high quality death registration rates more accurately. But those rates are still not split by sex. UPDATE DEC 9, 2024: OWID has now made it possible to see trends split by sex.]

In sum, it appears that both the WHO Global Health Estimates and the Global Burden of Disease Study have been underestimating youth suicide rates since 2010 across many countries around the world. However, when using national high-quality death registration data, I have consistently found a pattern that suicide rates have been rising for adolescent girls across the Anglosphere and in the more wealthy, secular, and individualistic nations since the early 2010s.

Why suicide rates are not enough

There is one last point I want to make. Even though some agree that rates of suicide are rising for teen girls (and this is happening in many nations), they have argued that we are creating a panic over a “small” rise in suicide rates. And, in the process, we are missing the big picture by not looking at groups who have much higher rates (such as middle-aged men).

It is true that compared to adults (and males), teen girls die by suicide at very low rates. For example, teen male suicide rates are just about three times higher than teen girls, and their high and rising rates are not discussed enough, as Richard Reeves has shown. It is essential that we understand this context and its implications so that we orient resources based on these facts.

[NOTE: Even though the rates for teen girls are low, they are not negligible. To put these statistics in perspective, if the suicide rate for 10-19-year-olds remained at its 2010 levels, there would be more than 3,000 girls and 5,000 boys still alive today.]

But here is the broader point I want to make: Suicide is a sex- and age-specific phenomenon. Young children rarely die by suicide, while adults do so far more often. Men almost always die by suicide at higher rates than women. This is not because the average adolescent or woman is that much happier than the average adult or man. Instead, there are many cultural and biological forces that drive individuals from some groups to die by suicide at higher rates than individuals in other groups (a topic for another post).8

In other words, we cannot assume just because rates of suicide for teen girls are low that teen girls are not struggling in unprecedented ways. If we want to get a clear view of adolescent mental health, we need to look at a range of measures—from depression and self-harm (which is far more common among adolescents) to suicide rates. If we decide to narrowly focus on only one of these measures, we are sure to miss an enormous amount of important information and context about the well-being of young people.

My point is this: if we dismiss rises in teen girls' suicide rates because they are “low” and then do not account for other—more common—mental health problems among teen girls because the measures are imprecise, then when exactly should we start paying attention?

Conclusion

My goal in this post was to address some counterarguments offered by some researchers who are skeptical that there really has been a rise in rates of adolescent mental illness. They think that American and British societies are now in the grip of a moral panic and that Jon and I are fomenting that panic with our charts, graphs, and claims about the “great rewiring of childhood.” We disagree. As I have shown here, three of the most common critiques are challenged by the international trends. We think it is time to start taking action.

One of our reasons for starting this Substack was to draw out such criticisms and then address them. We invite you to check our work and draw your own conclusions. Let us know if you think we are wrong.

Clarification of our argument: We argue that since the 1980s, children began to be systematically deprived of a “play-based childhood” (where kids have an enormous amount of free play, social interaction, independence, and responsibility in the real world to wire up their brains to thrive as adults). Between 2010 and 2015, this “play-based childhood” was fully replaced by the “phone-based childhood” (where kids spend most of their time on devices and do not experience the free play, independence, and responsibility that they need in the real world to thrive as adults). We argue that the mechanisms of harm—on average—from the “phone-based childhood” are different for boys and for girls, with girls being harmed most substantially from the combination of smartphones and social media platforms, while boys have been harmed in a more diffuse way, and most substantially from the ways that smartphones, social media, video games, and the host of other virtual activities have pushed out much of their real-world interactions, friendships, sleep, and exertion in the real world.

Note that there has been a bedding crisis in psychiatric hospitals around the country where there is more demand than supply, leading many people being stuck in emergency departments waiting to get into hospitals for care.

Self-harm among 20-24 year-olds is also rising, but is not visible in the figure as they are merged with the 25-29 year-olds.

We see similar age specific patterns in Australia, with rises only happening among girls and young women. I have not seen data for adults in Canada, the UK, or New Zealand.

I have found no indications that there were similar screening or insurance changes in Canada, the UK, Australia, or New Zealand from 2010 to 2015. Please let me know in the comments if I am missing something.

Contradiction #4: The changing diagnostics hypothesis predicts that there should be no increase in primary coding for suicidality or self-harm if the primary driver of the rise in hospitalizations were due to increased incentives to use secondary mental health codes (e.g., suicidality in addition to a primary code like depression). But we do see a substantial increase in primary coding for suicidality and self-harm.

A 2023 study of pediatric (ages 3 to 17) mental health hospitalizations from 2009 to 2019 addresses this contradiction. Using the KIDS inpatient database, a nationally representative database of U.S. acute care hospital discharges, they found that there had been an increase in total annual mental health hospitalizations from (an estimated) 160,499 patients in 2009 to 201,932 in 2019. They found that these increases happened across all races, all income brackets, and across all insurance types. Most notably, for this argument, they found a 66% increase in primary codes of “suicide or self-injury”, rising from 11,889 in 2009 to 17,997 in 2019. In other words, more kids were being admitted to hospitals for the primary reason of suicidality and self-harm. What this means is that kids are not just being given additional codes; they are going to the hospital specifically because they are presenting symptoms of suicidality and self-harming behavior.

Also note that this same study found a decline in hospitalizations for “schizophrenia,” “disruptive, impulse control, conduct disorders,” “substance abuse and addiction,” “ADHD,” and “bipolar and related disorders.” (Now, it is possible and likely that some bipolar coding was shifted to be covered by depression, which grew at a very rapid rate from 2009 to 2019). But my overall point is that kids are being hospitalized more for specific kinds of mental health conditions: internalizing disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, self-harm, suicide, and eating disorders), while not being hospitalized for other kinds of disorders (e.g., psychotic disorders or externalizing disorders such as “disruptive, impulse control, conduct disorders.” Internalizing disorders are the exact problems we expect to worsen from the phone-based childhood.

The WHO MDB rates map on to CDC rates.

Thanks for continuing to patiently respond to the skeptics with data-driven and logic-driven responses. I appreciate people want to hang on to long-held beliefs, but your work is important in helping come to the truth so we can make changes that will actually have positive impacts on our kids (or at least the next generation).

A major driver of mental health problems is changes in the omega-3/6 balance of the food supply due to increased arachidonic acid intake. But who is paying attention to that? For the latest word on that aspect of the suicide problem, read Omega Balance by Australian zoologist Anthony Hulbert, PhD.

Excerpt from a research paper: "The present findings suggest that, as naturally absorbed nutrients, higher EPA and lithium levels may be associated with less suicide attempt, and that higher arachidonic acid levels may be associated with more deliberate self-harm." (web search - Naturally absorbed polyunsaturated fatty acids, lithium, and suicide-related behaviors)