The Youth Mental Health Crisis is International, Unless You Rely on a Flawed International Dataset (The GBD)

Researchers need to stop using the Global Burden of Disease study when analyzing mental health trends

[CORRECTION: Our original text of this post had asserted that Our World in Data uses the GBD for many of their analyses. We want to clarify that they are *not* relying on the GBD for countries with high quality death registration data. For those countries, OWID generally relies on the WHO Global Health Estimates (GHE) suicide rates. I (Zach) apologize for this mistake.

Importantly, the WHO GHE has also been underestimating youth suicide rates since the early 2010s in many countries around the world (including nations with high-quality death registration data such as the U.S., UK, Australia, France, etc.). For more on the WHO GHE, read this post.]

[Note from Jon Haidt:]

A recent paper by Matti Vuorre and Andrew Przybylski garnered a fair amount of attention for its claim that, at a global level, they can’t find evidence linking an increase in youth mental illness to the arrival of the internet or mobile broadband adoption. Zach and I were interested in this finding because we have an entire section in our main review document that collects “quasi-experiments” about what happened to youth mental health as high-speed internet came to town, and all 5 of those studies found harmful effects. (See a summary of the studies here.) Why do we reach conflicting conclusions?

As we read the Vuorre paper, we noted that it relied heavily on a particular dataset for its measures of youth mental health – a dataset called the Global Burden of Disease study. Relying on that study, they report that there actually has not been much of an increase in youth mental illness in the past 15 years, but this also contradicts our findings. Again, what gives?

We decided to see for ourselves whether the GBD study is reliable. It is not, as Zach shows below. It fails to detect known rises in depression, self-harm, and suicide, in countries like the U.S. the UK, and Australia, where there is excellent data. Therefore the GBD cannot be used to evaluate whether the arrival of the internet had any effects on youth mental health.

– Jon Haidt

Some researchers still question whether the youth mental health crisis is an international crisis or just an American one. In a previous post, I discussed how some researchers argue that although suicide rates have been rising for American adolescents since the late 2000s, there does not seem to be any clear international pattern.

If rates were mostly constant or falling in most countries around the world, that would contradict a core argument that Jon and I have been making: that there is an international mental health crisis among adolescents—consisting of rapid rises in anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicide since the early 2010s—particularly among girls and those from English-speaking nations around the globe (We have also found that the rises in youth anxiety and depression happened in the five Nordic nations, and have found evidence of a global rise in adolescent loneliness). Why do some researchers see a multi-national rise in suicide and a variety of mental illnesses, while others see no such international trends? I dug into the international data and concluded that the differing results depend on four analytical choices:

Do you analyze boys and girls separately or together?

Do you look at data for 10-14-year-olds (where the increases are often larger)

Do you compare how young people are doing relative to older people in each country.

Do you examine regional patterns (e.g., Western vs. Eastern Europe) or cultural groupings of nations (e.g., degrees of individualism)?

In fact, when these points are considered, we do find an international rise in youth suicide. Using official national suicide data in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, we found that Gen Z girls and young women—in each country—had the highest rates of suicide of any recent generation.

Here’s a figure showing the suicide trends we found in all five nations:

Figure 1. Suicide trends among adolescent girls (ages 10-19) in five Anglo countries. From Suicide Rates Are Up for Gen Z Across the Anglosphere, Especially for Girls.

For boys, the rates were always much higher, but the suicide trends were more varied across nations. These trends revealed an important backstory: across all five nations, boys’ suicide rates were at historically high levels in the 1980s. In all five nations, rates began to plummet in the 1990s and early 2000s. And in four of these nations, rates began rising again in the late 2000s or early 2010s (Canadian boys did not rise much).

But there was a fifth point that I did not make in that post, and it may be more substantial than any of the above: Many researchers and organizations, such as the World Health Organization1 rely on the Global Burden of Disease study (entirely or partially) for their data on international suicide rates. That turns out to be a big problem.

On the surface, the GBD appears to be a highly sophisticated estimation tool for international health and disease: It is run by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington and has an enormous database (covers 204 countries, 369 diseases, and millions of people) that integrates data from many different sources—household surveys, civil registration and vital statistics, disease registries, health-service-use statistics, government and hospital databases, disease notifications, and others—to estimate mortality and disability across countries, time, age, and sex. Regarding mental health, they use these data to estimate yearly prevalence rates (per 100,000 individuals) of anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, self-harm episodes, and suicide.2

As I looked into the studies using the GBD, I noticed that the yearly mental health estimates (e.g., U.S. youth self-harm rates) were often much lower than what was reported in the validated national databases that Jon and I use. In fact, this point was acknowledged in a recent article that used the GBD, by Matti Vuorre and Andrew Przybylski. The authors claim to have shown that “the past 2 decades have seen only small and inconsistent changes in global well-being and mental health that are not suggestive of the idea that the adoption of Internet and mobile broadband is consistently linked to negative psychological outcomes.” Yet the authors note the potential weakness of the GBD study:

We emphasize that the GBD estimates are not observed data and therefore are accurate only to the extent that the GBD’s data-collection methods and modeling strategies are valid. We compared the GBD estimates with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (2022) estimates of self-harm in the United States and found that they are likely to deviate in systematic ways from other authoritative information sources. We nevertheless argue that because the GBD provides the most comprehensive data set of global mental health, studying these estimates is informative but emphasize this caveat.

In other words, the GBD is not actual data, collected from people or about people. It is not an attempt to measure something about a population. It is an unusual and interesting effort to estimate what the levels of various disorders might be, given a bunch of other variables that are available. This could be a valuable resource for studying mental health around the world, given that most of the 204 countries covered by the GBD simply don't collect any reliable data on mental health. But it’s only a valuable resource if the estimates prove to be pretty reliable. Are they?

For mental health, no. In the rest of this post, I will walk you through my process of answering this question by comparing the GBD estimates for the U.S. to the known rates of youth depression, self-harm, and suicide. If the GBD can’t estimate well for the U.S., where it can make extrapolations from excellent data, what chance is there that it will produce reliable estimates for China, Paraguay, Iran, or Cameroon?

I will show that the GBD—in every case that I looked at—systematically and substantially underestimates official statistics, and fails to detect the large increases that happened in the 2010s. Therefore the GBD should not be used when trying to understand changes in youth mental health or the causes of those changes.

Major Depression

Among the most authoritative sources on depressive episodes in the U.S., the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) conducts interviews with over 200,000 Americans every year. The survey includes validated measures on major depressive episodes for American adolescents, ages 12-17. Figure 2 shows a sharp rise in major depressive episodes among adolescent girls beginning around 2012. For boys, rates are also increasing, though the base rates are significantly lower.

Figure 2. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data, the percentage of U.S. adolescents with a major depressive episode in the last year has risen since 2004, with the upturn beginning around 2012 (ages 12-17). NSDUH does not provide data for 10- and 11-year-olds. Source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. See Zach’s spreadsheet for data points.3

The GBD—which aggregates numerous different data sources and then estimates population rates each year—produced very different results. Figure 3 shows that, according to the GBD, there was practically no change in depression rates for 10-14-year-olds from 2004 and 2019.

Figure 3. According to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data, prevalence rates of U.S. adolescent depression have been steady since 2004, ages 10-14. Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Burden of Disease. The GBD defined Major Depression using ICD10 F32–F33.9.

The 15-19-year-olds look very similar, except that the GBD estimates that rates of depression among both girls and boys have actually declined over the last decade.

Figure 4. According to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data, prevalence rates of U.S. adolescent major depression have been steady since 2004, ages 15-19. Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Burden of Disease. The GBD defined Major Depression using ICD10 F32–F33.9.

In other words, when we compare the GBD estimates of adolescent depression to known changes in the observed rates of adolescent depression, the GBD fails to capture what happened to adolescents in the 2010s. It also appears to hugely underestimate depression rates. For example, only 7.6% of girls 15-19 are depressed in the GBD estimates, compared to 28% of 12-17-year-olds in NSDUH in 2021. These are somewhat different age groups, but not different enough to explain the NSDUH rates being more than three times as large.

Because the NSDUH relies on self-report measures, we should also look to more objective behavioral data, like self-harm episodes, to see if the GBD performs any better in its models and estimates of other mental health metrics.

Self-Harm Episodes

The CDC has been collecting non-fatal self-harm emergency department visits and hospitalizations among American adolescents for over two decades. (The CDC uses data obtained from an expansion of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) operated by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). The NEISS collects data from a nationally representative sample of 100 U.S. hospital emergency departments.)

What does the comparison between CDC self-harm data and GBD estimates look like? Figure 5 shows self-harm rates among 10-14 year-olds, according to the two datasets. Once again, the GBD fails to pick up any sign of the adolescent mental health crisis.4

Figure 5. According to CDC data (left side), U.S. adolescent (ages 10-14) emergency department visits for self-harm have been rising rapidly, particularly among girls. According to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates (right side), self-harm prevalence rates among U.S. young adolescents (ages 10-14) have risen slightly for girls and declined for boys. Sources: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Burden of Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control WISQARS database. See Zach’s CDC spreadsheet for data points.

According to the CDC data, there has been more than a doubling of emergency department visits for non-fatal self-harm among both boys and girls since the early 2010s. The GBD, on the other hand, estimates that rates have been mostly steady, with small rises among girls. (Also, note that the GBD base rates are lower by a factor of 10.)

Figure 6 shows similar discrepancies among 15-19-year-olds.

Figure 6. According to CDC data (left side), emergency department visits for self-harm episodes have been rising rapidly, particularly among girls. According to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data (right side), prevalence rates of U.S. adolescent (ages 15-19) self-harm have risen slightly, but significantly less than CDC data. Sources: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Burden of Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control WISQARS database. Zach’s spreadsheet for data points.

Overall, for both depressive episodes and non-fatal self-harm, the GBD’s effort to estimate rates produces findings that are divorced from the reality we see in federal datasets that measure observed rates. But the best mental health data we have—with the clearest and most objective data—are youth suicide rates.

Suicide Rates

Figure 7 compares the CDC’s adolescent suicide rate with GBD estimates. Here, the GBD produces trend lines that are at least connected to the documented changes in rates of suicide. The GBD estimates correctly show that the rate for preteen girls was fairly flat in the 2000s and then went up in the 2010s, although it massively understates the known increase (36% vs. 179%). For boys, the GBD performs even worse. It captures the decrease in the 1990s and 2000s, but it takes a 137% increase in the 2010s and converts it to a 24% increase, suggesting that today’s suicide rates are not as high as they were in the early 1990s. This is false.

Figure 7. According to CDC’s WISQARS Fatal Injury Report data, suicide rates have been rising since around 2008, for both boys and girls. According to GBD estimates, rates followed a similar pattern, but did not rise nearly as much as CDC data reflects. (see Zach’s spreadsheet for CDC data). I intentionally report the CDC data up to 2019 to easily compare it against the GBD.

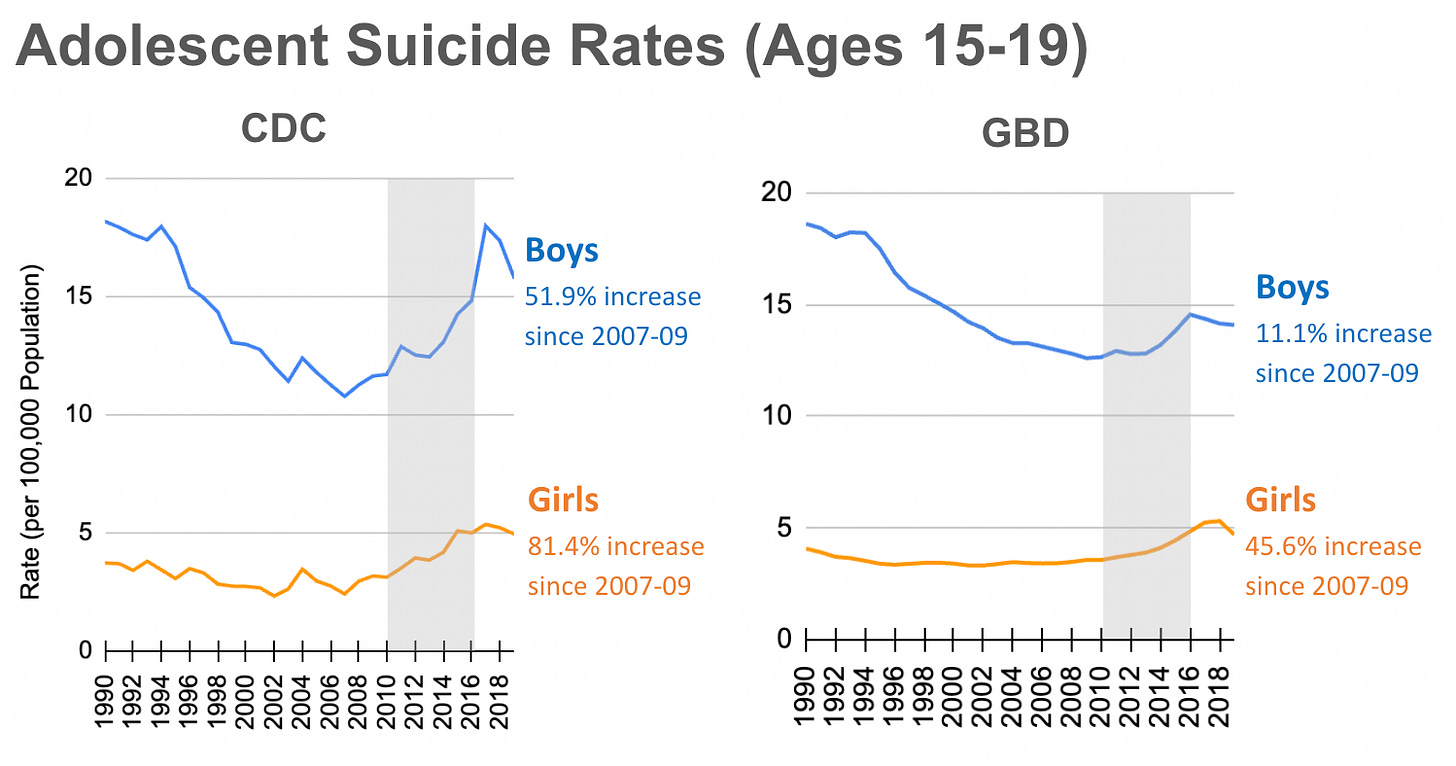

The 15-19-year-olds show similar underestimates from the GBD, as you can see in Figure 8.

Figure 8. According to CDC’s WISQARS Fatal Injury Report data, suicide rates have been rising since around 2008, for both boys and girls. According to GBD estimates, rates followed a similar pattern, but did not rise nearly as much as CDC data reflects. Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Burden of Disease. (see Zach’s spreadsheet for CDC data). I intentionally report the CDC data up to 2019 to easily compare it against the GBD.

In sum: In every case that we have looked at, the GBD severely underestimates mental health changes since 2010. The GBD fails to detect very large increases in depression, self-harm, and suicide in the U.S., where the GBD can draw on a great deal of high-quality data to inform its estimates. I also took a look at how GBD suicide estimates compare to national data from England and from Australia for two additional comparison points. I found similar post-2010 underestimates.5 How much faith should we put in GBD estimates for the other 201 countries, most of which lack the kind of high-quality long-term studies conducted by the U.S. government? None, I believe.

Conclusion: Type I and II Errors

When I was in college, my statistics professors regularly warned me of a great danger in scientific research: We are often wrong when we think we are right.

My professors told me that this danger plays out in two ways: (1) we think something is happening when it isn’t or (2) we think something is not happening when it is. There are technical terms for these mistakes: Type 1 and Type 2 errors.

This is an image one of my professors used to explain the difference:

Figure 9. A Type 1 error is finding an effect when there is not actually anything going on (e.g., being told you are pregnant when you are not. It’s a false positive). A Type 2 error is the opposite: not finding an effect when there actually is something going on (e.g., being told you are not pregnant when you are. It’s a false negative). Source: Yao (2014).

In science, we treat Type 1 as a much more serious error. We think it’s much worse for a false finding to make it into a journal and then out into the world, than for a true finding to be kept out of a journal for a while. Although this can also be true from a public health perspective, there are many cases where Type 2 errors pose an especially high concern for health. In public health, for example, if you conduct a study and find no relationship between smoking cigarettes and lung cancer, and if the reality is that there is a relationship, the potential health consequences would be enormous. Thus, from a public health perspective, the higher the health costs of not finding an effect when there is one, the more concerned we should be with making a Type 2 error.

This simple framework of Type 1 and 2 errors can help explain the years-long debate about social media and mental health. Skeptics of the relationship are very concerned about making a Type 1 error and believe we are making one. Specifically, we say there is a relationship between smartphones/social media and mental health outcomes when in reality, there might be none. We, on the other hand, are very concerned about making a Type 2 error and believe that skeptics are making one: They say there is no relationship between smartphones/social media and mental health outcomes when in reality, there is one. We believe the health costs of making a Type 2 error are catastrophically high, while the skeptics appear more concerned about the costs of making a Type 1 error.

If we make a Type 2 error and say there is nothing going on when in reality there is, then the adolescent mental health crisis will continue to surge, around the world, year after year, as we continue giving our children smartphones at younger and younger ages.

What happens if we make a Type 1 error? Children would not be given smartphones and social media until a later age, perhaps 14 or 16, when in fact they could have had them earlier. This cost seems rather trivial to us. (We also would have diverted some time, energy, and money from whatever the real culprit of the crisis is. But as far as we know, there is no other explanation for the crisis that works internationally.)

Judging by its poor performance in the U.S., the GBD seems destined to cause many Type 2 errors.6 It does not detect the largest increases in youth mental illness ever recorded in the U.S. Therefore it cannot be used to study the causes of those increases, in the U.S. or in any other country.7

The GBD may be useful for estimating rates of other diseases, or rates of mortality. But until the GBD is able to accurately and reliably estimate youth mental health trends, researchers should stop using this data source for making claims regarding the influence of social media—or anything for that matter—on youth mental health.

The youth mental health crisis may not be happening in all countries around the globe, but as I have shown so far, it seems to be happening in most wealthy countries that have high levels of individualism and adolescent smartphone adoption. It is not just an American phenomenon, so the search for causal factors must focus on factors that could have affected many Western countries at the same time, in the early 2010s. We have proposed that the cause of this rapid international change was the transformation of childhood from play-based to phone-based, when most adolescents traded in their flip phones for smartphones from which they could access the internet all day long.

Nobody, to our knowledge, has yet proposed another explanation that works internationally. (If you have one, please put it in the comments.)

Note that the WHO uses the GBD for nations which do not have high quality national suicide data.

You can download all GBD data used in this post here: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/

To determine the relative change in suicide rates throughout this post, I average the suicide rate for the three years before the Great Rewiring, 2007-2009, and I compare it to the three years before the COVID pandemic began in 2020, 2017-2019. This gives us a stable and consistent measure that is not contaminated by the effects of the pandemic and its associated restrictions.

The GBD defined self-harm using the ICD10 codes: X60–X64.9, X66–X84.9, Y87.0.

You can view these analyses in the supplemental Google Doc for this post.

Note that other recent reports (not relying on the GBD) have made similar-in-outcome errors, with substantial under-reporting of changes in youth suicide. See for example David Stein’’s recent critique of the National Academies Report, Adolescent Suicide Nonsense in National Academies Report.

The GBD is—in part—why the OWID suicide estimates are inaccurate. OWID derives its suicide data from the GBD for some of its figures and WHO Global Health Estimates for others, which, like the GBD, uses a variety of sources to estimate national suicide rates—including the GBD, especially for countries with minimal actual suicide data. Interestingly, the WHO suicide estimates for the U.S. diverge (underestimate) significantly from both the CDC data and the GBD. See Figure 3 in the supplemental doc. In a future post, I will discuss the issues with the WHO estimates.

Excellent article on methodology. Just speculating, but I wonder if the GBD data might be used as a controlling variable. In other words, it might be used to show expected mental health based on our current theories vs. actual mental health. A deviation between the two that can be explained by mobile device usage would tend to support your theory.

I do not doubt nor question the rigour and probity of the research discussed in this post. But I do wonder whether it entirely manages to avoid being affected by (what I would call) The Mental Health Industry's relentless expansion of the concept in recent times. In pop-psychology, plain old-fashioned human UNHAPPINESS has increasingly been redefined as a mental health problem. Reassure me that mental health research does factor this in.