The Teen Mental Illness Epidemic is International, Part 2: The Nordic Nations

For Teens, Scandinavia is No Longer The Happiest Place On Earth.

Today we have Zach’s second post on how teen mental health is changing around the world. In his last post, Zach showed that there is a four-part pattern in the data from all five of the main “Anglosphere” countries. Today he presents the studies he has collected on teen mental health in the five Nordic nations (the three Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, plus Finland and Iceland).

The Nordic nations differ in many ways from the Anglosphere countries. In particular, they have lower levels of some of the social pathologies that some have said might explain the rising levels of mental illness in the USA such as income inequality, a hyper-competitive neoliberal economy, school shootings, and other gun violence. The Nordic countries also seem to do a lot less of the “coddling” and paranoid overprotection that is rampant in the USA, Canada, and the UK (though not so common down under).

And yet, as you’ll see, the basic pattern largely holds. I think these two posts from Zach are tremendously important for they show us that the teen mental illness epidemic is international. We need to be looking for causes that can explain the international pattern, even as we know there are also additional causes and cultural interactions specific to each country.

— Jon Haidt

A few weeks ago, Finland was ranked the world’s happiest nation for the sixth year in a row. The other Nordic nations—Denmark, Iceland, Sweden, and Norway—were not far behind, ranking second, third, sixth, and seventh, respectively. A year ago, If I had been asked to predict who the happiest teens on earth would be, I would have placed my bets on them. Wouldn’t you?

1. Teens Living In The Shadow of Happiness

Around the same time that I began collecting studies on mental health trends in the English-speaking world (which I discussed in my first post), Jon and I began another Collaborative Review Google Doc, “European Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010: A Collaborative Review.”

But the document quickly became so long that we needed to split it by region. We created another Google doc (we are now at 22) focused entirely on the five major Nordic nations: Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland. It’s titled “Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010: A Collaborative Review.”1

I initially expected that mental illness trends in these five nations would substantially differ from those seen in the Anglosphere. Compared to the English-speaking world, Nordic nations have excellent social safety nets, stronger social trust, healthcare systems considered among the best in the world, and encourage more unsupervised risky play. I had expected that whatever was causing the mental illness epidemic in the Anglosphere was probably not causing as much suffering among Nordic teens.

In the process of curating the new Google doc, I came across a 2018 report by the Nordic Council of Ministers titled “In The Shadow of Happiness.” The report explores the hidden suffering that lies just beneath the surface for many Nordic people. The authors examine a number of different factors that explain variation in well-being, including income, religiosity, country, and employment status.

But what quickly became clear to me was that across all five countries, just like in the Anglosphere, many young women are suffering, and suffering in much larger proportions than any other age/gender group (Figure 1).2

Figure 1. The proportion of Nordic women often or always feeling depressed (2012-2016). Data from the European Social Survey. Regraphed in ”In the Shadow of Happiness.”

The age disparities in Nordic women are not mirrored in the data for men. Young Nordic men are not generally doing worse than older Nordic men.

Figure 2. The proportion of Nordic men often or always feeling depressed (2012-2016). Data from the European Social Survey. Regraphed in ”In the Shadow of Happiness.”

This report provided me with the first clue that despite Nordic dominance of nearly all of the world’s happiest countries lists, for many years, something is going wrong for Nordic girls and young women.

Do these findings hold up in other studies, including those on formal diagnoses of anxiety and depression, hospitalizations for self-harm, or psychiatric emergency department visits? And do we know if Nordic girls and young women have always been more unhappy than others, or is this a new phenomenon?

In the rest of this post, I will address these questions and show how teen mental health has changed in the five Nordic nations since around 2010. I will share both self-report data (e.g., reports of depression and anxiety) along with behavioral data when possible (e.g., self-harm rates or psychiatric hospitalizations).

I will explore whether each of the five Nordic nations shows the “basic pattern” that had emerged in all five of the Anglosphere nations:

A) A substantial increase in adolescent anxiety and depression rates begins in the early 2010s.

B) A substantial increase in adolescent self-harm rates or psychiatric hospitalizations begins in the early 2010s.

C) The increases are larger for girls than for boys (in absolute terms).

D) The increases are larger for Gen Z than for older generations (in absolute terms).

The short answer is: The mental health of teen girls, based on self-report measures, has been declining, often sharply, in all five Nordic nations since the early 2010s. However, on the self-harm and hospitalization data, the pattern is more convoluted, particularly in Sweden and Denmark, where some behavioral measures don’t align with the self-report data. I’ll discuss these discrepancies near the end of this post. As in my previous post, I am more interested in the absolute increases, but I report the relative increases too, on the graphs because they are harder for the reader to calculate.

2. Changes Across The Five Nordic Nations, Combined

In 1986, the World Health Organization initiated one of the most comprehensive international health surveys for 11-15-year-old adolescents: The Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC). Conducted every four years in dozens of European countries, including the five major Nordic nations, the WHO provides open access to all data after 2002, making the survey an excellent resource for examining whether psychological health in young teenagers in the Nordic region has declined, as it has in the English-speaking world.

Jon and I teamed up with Thomas Potrenby, Associate Professor in the Department of Health and Functioning at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, who researches global adolescent mental health and has published numerous cross-national studies using the HBSC. The HBSC includes four items that map onto different dimensions of psychological distress: feeling low, feeling nervous, feeling irritable, and having sleep difficulties. Respondents rated how often they felt these four symptoms over the last six months (1: Every day, 2: More once/week; 3, About every week; 4, Every month; 5, Rarely or never). With Thomas’s support, we organized the HBSC data to observe trends in high psychological distress (which we operationalized as having three or more of the four psychological ailments at least once a week over the last six months) among 11-15-year-old Nordic boys and girls since 2002.

After pooling the data and weighting scores based on each Nordic nation’s population size, we discovered that, before 2010, little change occurred. However, by 2018, the percentage of girls reporting high levels of psychological distress rose by eight percentage points, from 11.0% in 2010 to 19.4% in 2018, a 76.3% relative increase (see Figure 3). Similar trends appeared among boys, increasing from 5.5% in 2010 to 8.3% in 2018 (a 51.3% relative increase).

Figure 3. Percent of Nordic Teens with High Psychological Distress. Data from the Health Behavior in School-Age Children Survey (2002-2018). Graphs and data were organized, analyzed, and created by Thomas Potrebny and Zach Rausch. See 1.1.1 of Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

When we zoomed in on individual countries, we observed increases in psychological distress among boys and girls in all five Nordic nations (except for Norwegian 11-year-old girls, who experienced declines in psychological distress). The HBSC data for each country can be found in 1.1.1 of Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) assessment is another valuable resource for observing changes across Nordic nations, as it collects data from thousands of students from each of the five countries (among others). PISA is all about education, not mental health, but since its inception, the survey has included six items to measure school loneliness, such as “I feel lonely at school.”3 Jon, Jean Twenge, and colleagues (2021) examined whether trends in school loneliness have changed worldwide in recent years and whether those changes varied regionally. I dug into the study and pulled the data for each of the five Nordic nations.

Figure 4. Increases in adolescent loneliness, Nordic nations. PISA data, 2000-2018. Responses are from 1 to 4 with higher scores indicating more loneliness. Graphed by Zach Rausch. Source: Twenge, Haidt, Blake, McAllister, Lemon, & Le Roy (2021). Note that the loneliness items were not included in 2006 or 2009. See 1.1.3 of Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010 for these data and the statistical tests. (Updated April 20: I had put the wrong relative percent increase for Iceland).

As you can see in Figure 4, the rise in school loneliness from 2012 to 2018 is relatively small, however, the timing is striking. There’s no real sign of much change from 2000 to 2012 and then suddenly, loneliness increased in each of the five nations, and the majority of that increase occurred between 2012 and 2015. The effects were gendered, with loneliness increasing faster for girls than boys.4

From this high-level vantage point, we see the basic pattern beginning to re-emerge: Across Nordic nations, there is a substantial increase in poor mental health and loneliness that begins after 2010, and that increase is larger for girls than boys, in both absolute and relative terms.

Let’s now dive into data collected within each of the five Nordic Nations, moving from East to West.

3. Finland

In 2002, researchers began collecting data on 9th-grade students (15-years-old, N = 4,162) in Tampere, Finland’s second-largest urban area. They examined externalizing mental health symptoms (e.g., aggression, impulsivity, and inattention) and internalizing mental health symptoms (e.g., sadness, anxiety, and loneliness) at three-time points (2002-03, 2012-13, and 2018-19), which allows us to see trends before and after 2012.

From 2002 to 2018, the prevalence of externalizing symptoms decreased for both boys and girls, a finding consistent with United States trends. However, internalizing symptoms, including depression, social anxiety, general anxiety, poor subjective health, stress, and poor self-esteem remained unchanged between 2002 to 2012 but spiked between 2012 and 2018 (also consistent with U.S. trends).

Figure 5 displays the rise in one of the internalizing symptoms: the percentage of teens with depression, as measured by a Finnish adaptation of the Beck Depression Inventory.

Figure 5. Changes over time in depressive symptoms among adolescents in Tampere, Finland. Data from a school survey among 9th graders, 2002-2018-19. See 6.1.2 of Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

Similar results can be found in other studies (e.g., Mishina and colleagues (2018), though the study only includes data until 2014 and the rises are not as large), while others show important variations. Using Finnish School Health Promotion data, one study tracked the prevalence of generalized anxiety of over 750,000 Finnish youth aged 13–20 from 2013-2021. Among girls, generalized anxiety moderately increased from 15.5% in 2013 to 19.7% in 2019 (a 27.1% increase) and spiked sharply between 2019 and 2021, rising by 53.3% (from 19.7% to 30.2%). Rates for boys remained stable from 2013 (6.0%) to 2019 (5.5%) and increased in 2021 (to 7.7%). The study suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may have had a more significant impact on teenage anxiety than whatever was causing the prior increase.

As mentioned in my first post, self-report studies are important but changes over time could reflect factors other than increases in mental illness. Figure 6, with data from the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare, shows the rates per 100,000 Finnish teens diagnosed with an anxiety disorder as a primary diagnosis after inpatient psychiatric treatment in the last year. Unfortunately, the available database only includes data beginning in 2012, so we cannot see trends before and after 2010.5

Figure 6. Anxiety Diagnosis after Inpatient Psychiatric Treatment in Finland. Data from the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare. See 6.2.2 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

The results indicate that anxiety diagnoses increased from 130.0 per 100,000 girls in 2012 to 242.3 per 100,000 in 2021 (an 86.4% increase). Rates also rose for boys, but the absolute and relative change was smaller (29.6 per 100,000 to 41.23 per 100,000, a 39.3% increase).

The trends for depression diagnoses after inpatient care were similar, but the rise in diagnoses occurred a bit later (2015-16 for girls and 2016-17 for boys; refer to the graphs and data in 6.2.2 of Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.)

I was unable to find Finnish data on deliberate self-harm or cross-generational comparisons. If you know of studies or data sources, please share them in the comment section below.

Overall, the basic pattern mostly appears in Finland, though there is still some missing information: Anxiety and depression have significantly increased among both boys and girls since around 2012, with the largest increases in girls. In three of the four studies, poor mental health spikes began before the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, it is unclear whether the self-harm rates have increased since around 2010, and if younger generations are faring worse than older generations.

4. Sweden

The Swedish Public Health Agency has conducted a nationally representative health survey (aka, The Swedish National Health Survey) of Swedes ages 16-84 since 2004. Figure 7 shows the percentage of Swedish women, broken up by age group, who report having severe anxiety or worry across 14 data collection cycles.6

Figure 7. Swedish women with self-reported “severe anxiety or worry.” Data from the Swedish National Health Survey. See 2.1.2 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

The trends in anxiety look similar to the trends found in English-speaking countries. The youngest age group (16-29 years old) experienced the most significant rise in anxiety levels, from 8% in 2010 to 20% in 2021, a 150% increase. And as we move to the older groups, the increases decrease, with the oldest group of Swedish women actually reporting less anxiety in 2021 than that group had reported in 2010.

Figure 8 shows the corresponding trends in severe anxiety among Swedish men.

Figure 8. Swedish men with self-reported “severe anxiety or worry.” Data from the Swedish National Health Survey. See 2.1.2 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

Like Swedish women, the youngest age group has witnessed the most significant absolute and relative increase since 2010 (with the exception of those aged 65-84 which had a tiny absolute increase that translated into a large relative increase due to its very low level). In 2010, 5% of 16-29-year-old men experienced severe anxiety, which doubled to 10% by 2021.

It is important to note that prior to 2010, young Swedes (both males and females) reported anxiety levels nearly identical to older cohorts. However, this changed by 2016, with young adults experiencing anxiety rates two to three times higher than older age groups.

The Swedish National Board of Health and the Swedish Welfare's patient register offer another valuable data source on inpatient treatment and diagnoses for mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and deliberate self-harm.

Figure 9 plots the depression diagnosis rates per 100,000 Swedish women who underwent inpatient psychiatric treatment in the previous year. Since 2010, diagnoses for the youngest girls (10-14) have surged, rising from 16.3 per 100,000 in 2010 to 47.5 per 100,000 in 2021, a 191.41% increase. Meanwhile, 15-19 year-olds have risen from 141.4 per 100,000 to 195.8 per 100,000. In contrast, every other age group saw a decline in diagnoses since 2010.

Figure 9. Inpatient Care for Depressive Episodes, Swedish Women. From Statistics Database for Diagnoses (2006-2021). The Department for Registers and Statistics, Socialstyrelsen. Based on conversations with the Department for Registers and Statistics, I learned that psychiatric data from 1998 through 2005 were under-reported, with 23% of discharges from youth and child psychiatry not recorded in 2001 and 12% in 2005. To see graphs that begin in 1998, see 2.1.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

The trend among males is similar to that among females, with three key differences: (1) younger age groups have lower base rates, (2) the 15-19 year-olds do not surpass the rates of some of the older male groups, and (3) younger boys have considerably smaller absolute increases than the younger girls.

Figure 10. Inpatient Care for Depressive Episodes, Swedish Men. From Statistics Database for Diagnoses (2006-2021). The Department for Registers and Statistics, Socialstyrelsen. See 2.1.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010 for graphs beginning in 1998.

In 2010, 3.6 per 100,000 boys aged 10-14 were diagnosed with depression, which increased to 5.6 per 100,000 by 2021, a 55.6% increase. The rates for 15-19-year-olds climbed from 61.6 to 66.7 per 100,000 in 2021, an 8.28% increase. Although it may be difficult to discern in the figure, all other age groups displayed a decline in depression diagnoses.

Anxiety diagnosis rates followed a similar pattern to depression, except the rise of anxiety began in the mid-2000s for women and a decline among 15-19-year-old girls from 2017-19 (but the rise re-emerged in 2020). (refer to 2.1.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010: A Collaborative Review for graphs of both males and females).

Interestingly, the self-harm data did not align with anxiety and depression trends. Despite an increase after 2010 (from 38.4 per 100,000 in 2010 to 94.0 per 100,000 in 2021, a 144.8% increase for 10-14-year-old girls), the spike in inpatient diagnoses for deliberate self-harm only emerged once the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020. This deviates from the English-speaking countries, where the rise in self-harm rates was an extension of prior trends.

Figure 11. Inpatient Care for Deliberate Self-Harm, Swedish Men and Women. From statistics database for diagnoses (1998-2021). The Department for Registers and Statistics, Socialstyrelsen. See 2.1.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

In sum: The basic pattern is found only partially in Sweden. Rates of anxiety and depression have risen since 2010, though some data indicate an earlier onset for anxiety in the mid-2000s, while other sources highlight a more pronounced increase post-2010. Consistent with the basic pattern, young Swedes used to exhibit similar or lower rates of mental illness compared with other age groups, but this changed around 2017, particularly for girls. The increases were generally larger for girls than boys in both absolute and relative terms. Contrary to the basic pattern, rates of deliberate self-harm did not rise around 2010 but spiked (for girls) at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

5. Denmark

Starting in 2010, the National Board of Health and the National Institute for Public Health at the University of Southern Denmark have conducted a series of health surveys on Danish adults called the National Health Profile. The survey gathers data from thousands of Danes, aged 16 to 74, on various health matters, including mental health. Mental health is measured using the mental component of the Short-Form 12 (SF-12), which assesses self-reported mood and energy levels over the past four weeks on a 6-point scale. A score below 35.76 indicates poor mental health (corresponding to the lowest 10% of scores on the scale).

Figure 12 presents the percentage of Danish girls and women with poor mental health between 2010 to 2021 (across four data collection cycles: 2010, 2013, 2017, and 2021).

Figure 12. Percent of Danish Women with Poor Mental Health. Data from the National Health Profile. See 3.1.2 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

Between 2010 and 2013, poor mental health increased across all age groups, with the largest absolute increase among the 16-24 year-olds (though this rise was quite small). From 2013 to 2021, similar trends continued, but both the absolute and relative increases became much larger across all age groups. Young women aged 16-24 rose from 15.8% in 2010 to 34.4% in 2021, a 117.7% increase (the largest absolute increase across all age/gender groups). Notably, much of the rise in poor mental health preceded the COVID–19 pandemic.

Figure 13 displays responses from men to the same item.

Figure 13. Percent of Danish Men with Poor Mental Health. Data from the National Health Profile. See 3.1.2 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

As usual, the youngest male cohorts experienced the largest increases in poor mental health between 2010 and 2021. Rates for 16-24-year-old young men jumped from 8.3% in 2010 to 21.2% in 2021, a 155.4% increase (the largest relative increase across all age/gender groups). The 25-34-year-old men closely followed, rising from 9.3% in 2010 to 20.4% in 2021, a 119.4% increase.

In general, poor mental health increased for both men and women across all age groups from 2010 to 2021, with a particularly notable rise among young women aged 16-24 and young men aged 16-34.

But what does the behavioral data reveal?

In 2021, researchers Simon Victor and Anne Amalie Elgaard Thorup analyzed pediatric psychiatric emergency department visits in Glostrup, Copenhagen between 2012 and 2017. Using nurse-kept registration logs, they found a 50% increase in visits between 2012 and 2013 and a doubling of visits over five years, from around 1,000 visits to just over 2,000. Importantly, most patients were female adolescents, and the primary reason for inquiry was suicidality.

Figure 14. Trends in a pediatric psychiatric emergency room in Copenhagen, 2012-2017 (Ages 5-17). Graphed by Victor & Elgaard Thorup (2021). See 6.3.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

In contrast, a 2020 study in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology reported different results. Utilizing Denmark’s national administrative registers, the researchers tracked hospital-treated non-fatal self-harm from 2000 to 2016 for those individuals aged 10 to 19. As illustrated in Figure 15, self-harm rates peaked in 2007 for both boys and girls and then steadily declined for both genders through 2016.

Figure 15. Temporal trends in the annual incidence of self-harm by sex (3-year moving averages), ages 10–19 years. See 6.3.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010. The study does not provide detailed statistics for self-harm rates, which is why I do not include the percent change since 2010. Regraphed with a vertical line.

Because of the truly representative nature of the national register data, I am inclined to believe that the self-harm rates have indeed been dropping since 2012. However, the absence of more recent data prevents a clear understanding of whether self-harm trends remained low or increased, similar to other countries during this period.

Despite declining self-harm rates, the deteriorating mental health of Danish youth remains a significant concern for health leaders in Denmark. In September 2022, the Danish Health Authority and the WHO convened a meeting to address the growing mental health crisis among Nordic and Baltic nations. The report directly addressed the mental state of young Danes with the following remarks,

[There’s been an] increase in mental health conditions from 2010 to 2021, especially in young people, with nearly 35% of women and 20% of men aged 16-24 reporting poor mental health; and a huge increase in health-seeking behavior for hospitals over last 10 years, with nearly twice as many young people (<19 years of age) using hospital services for mental health.

In sum, the results in Denmark varied, with two studies and the report from the Danish Health Authority revealing declines in self-reported mental health and increases in psychiatric emergency department visits, while another showed declining rates of non-fatal deliberate self-harm among Danish adolescents.

6. Norway

The Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT), one of Norway's largest collections of health data, started gathering data on Norwegian adolescents in 1995-97, spanning four survey cycles. Krokstad and colleagues (2022) analyzed the HUNT data to determine the prevalence of subjective anxiety and depression symptoms stratified by age and gender from 1995 through 2019 over three data collection cycles.

Figure 16 shows depression and anxiety trends among Norwegian teens (13-19) from 1995-7 to 2017-19.

Figure 16. Norwegian Teens with Depression and Anxiety Symptoms, Ages 13-19. Data from cross-sectional population-based surveys from the young-HUNT Study. See 4.1.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

As you can see, before 2006-08, there was little change for boys and a rise in symptoms for girls. After 2006-08, boys began to rise, and the change became steeper for girls.

The HUNT study also provides data on anxiety and depression rates among older age groups. Figure 17 displays the percentage of women above the age of twenty with anxiety symptoms. Once again, the age groups were not very different from each other before 2010, but in the 2010s the levels for the youngest groups rise a lot, while the levels for the oldest groups say steady or decline.

Figure 17. Norwegian Women with Anxiety Symptoms, Ages 20-79. Data from cross-sectional population-based surveys from the HUNT Study. See 4.1.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

Anxiety trends among men mirrored those of women, with the most significant increases occurring in the youngest cohorts and the smallest in the oldest. A new interaction emerged for depression among both genders: individuals aged 20-49 experienced increased depression, while those above 50 experienced significant declines. Before 2006-08 those over fifty had the highest depression rates, but by 2017-19, those under fifty surpassed them. Among women, the highest depression rates by 2019 were seen in 20-29-year-olds, increasing from 19.1% in 2006-08 to 32.0 % in 2017-19, a 132.6% increase.

Figure 18. Norwegian Men and Women with Depressive Symptoms, Ages 20-79. Data from cross-sectional population-based surveys from the HUNT Study. See 4.1.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

Do other studies show similar patterns?

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health compiled a report on health quality nationwide. Analyzing multiple cross-temporal studies, they produced a graph illustrating psychological distress (symptoms of anxiety and depression) trends among 13-24-year-old girls from 1992 through 2019. Figure 19 shows that the percentage of girls with distress has been increasing since the early 1990s. All of the studies show an increase, and while none show the kind of sharp elbow that is found in most of the graphs in this report, the three studies that span 2012 do show an acceleration in the years after 2012 compared to before 2012.

Figure 19. Trends in psychological distress among Norwegian girls and young women (ages 13-24) among various Norwegian surveys. The surveys have measured and defined psychological problems differently. Graphed in Bang et al. (2023). Regraphed with English labels and a vertical line. See 4.1.4 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

Psychological distress also rose after 2010 for boys in 3 of the four studies post-2010, albeit with smaller absolute increases.

Figure 20. Trends in psychological distress among Norwegian boys and young men (ages 13-24) among various Norwegian surveys. The surveys have measured and defined psychological problems differently. Graphed in Bang et al. (2023). Regraphed with English labels and a vertical line. See 4.1.4 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

Thomas Potrenby has a pre-print of a meta-analysis looking at trends across the variety of Norwegian studies on psychological distress. Thomas and his colleagues note: “Combined, these studies show that self-reported mental health problems among young people have increased over the past three decades, particularly among females.”

I was unable to find high-quality self-harm or psychiatric hospitalization studies. If you know of any please let me know in the comments.

To recap: Norwegians show the basic pattern that we saw emerge in the English-speaking countries. Though results varied by study, anxiety, and depression rates have generally risen since the early 90s and have grown sharper since around 2010. The increases were larger for the younger age groups and larger for adolescent girls. It’s critical to find studies on deliberate self-harm trends.

7. Iceland

I have found two national studies that examine teenage mental health trends in Iceland. The first study, published in 2017, used data from 43,382 Icelandic adolescents aged 14-15 to investigate anxiety and depression symptoms trends from 2006 to 2016. Figure 21 reveals that rates of high anxiety were relatively stable for both sexes before 2010 but spiked for girls between 2012-2016.7 Trends were similar for depression, except the rates for girls began rising a bit earlier, in 2010.

Figure 21. Trends in high anxiety symptoms, Icelandic Teens. Data and graph from Thorisdottir, 2016, with a vertical line added by Zach Rausch. See 5.1.1 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010. I am still working on getting the data points for this graph in order to add the relative increases.

Overall, the researchers found,

For girls, there was a significant (P < 0.001) increase in mean levels of depressive symptoms between each time point from 2012 to 2016, as well as between 2009 and 2010. Anxiety symptoms increased significantly (P < 0.001) between 2012 and 2016 among girls. Mean levels of symptoms of depressed mood remained quite stable among boys; while mean levels of anxiety symptoms decreased significantly between three time points

The second study offers insights into how mental health trends have changed since 2016. From 2016 to 2020, 13-18-year-olds with depressive symptoms significantly increased over time from a mean depression score of 17.96 in 2016 to 18.54 in 2018 (a 3.2% increase from 2016) and 20.30 in 2020 (a 9.5% increase from 2018; scores ranged from 10 - 40, see footnote for details).8 Like the first study, the rates for girls were higher and steeper across the study period compared to boys. The figures from the study can be found in section 5.1.3 of Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

Like Norway and Finland, I was unable to find self-harm or psychiatric hospitalization data, leaving those questions unanswered.

In sum, anxiety and depression rates have climbed quickly since around 2012, and the rise has been particularly sharp for adolescent girls. We need more data on behavioral measures and cross-generational comparisons.

8. Conclusion

To what degree did each of the five Nordic nations align with the basic pattern that emerged in the Anglosphere? Table 1 below summarizes my findings (with “??” showing that I could not find any data for that country).

Table 1: The basic pattern within each of the five Nordic nations. “??” indicates that I have not yet found a study or dataset.

*Of the three Swedish sources on rates for girls, one showed a sharp increase begin in 2015 (self-reported severe anxiety), one in 2012 (diagnosed depression), and one in 2006 (diagnosed anxiety). (see 2.1.3 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010).

**The self-report measure was not for anxiety or depression specifically, but rather for “poor mental health.” See 3.1.2 in Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

As you can see, there is more variation and less data available, compared with the Anglosphere countries, four of which have much larger populations than Sweden (the largest Nordic country, with a population of 10.4 million). Nonetheless, the same trends appear to be emerging: Across all five nations, there has been a substantial increase in anxiety and depression since the early 2010s, the increase was larger for girls than boys, and it was larger for Gen Z than for older generations.

Self-harm and psychiatric hospitalization trends are less consistent, with some disconfirming evidence (i.e., declines in Denmark until 2016, and steady rates until COVID in Sweden). At this point, I do not know why these trends differ. Potential reasons for the occasional misalignment of these trends with anxiety, depression, and poor mental health trends are explored in Appendix A of Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010.

Importantly, when we zoom out and analyze the Nordic region as a whole, the basic pattern reveals itself to be nearly identical to what I found in Anglosphere nations, at least for depression, anxiety, and psychological distress. Figure 22 demonstrates that the increase in self-reported mental health problems among Nordic teens increased around the same time, in the same way, and to the same degree as in the United States (and other English-speaking countries).9

Figure 22. Comparisons between poor self-rated mental health in Nordic nations from the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children Study, and NSDUH data on teens with a major depressive episode in the last year.

This is why the WHO and Danish Medical Authority convened the first-ever Nordic and Baltic meeting on mental health, with an emphasis on changes among youth. This convening was not only designed to address the mental health challenges since COVID-19 but because:

There has also been a significant increase in poor mental health among young people over the last 12 years – particularly in loneliness and self-reported symptoms of mood disorders.

What has caused this increase in poor mental health among young people, especially girls, when the mental health of older men and women did not decline by nearly as much (as we see in Figures 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 17, and 18)? What changed in the late 2000s or early 2010s that primarily harmed the mental health of teen girls?

My goal in this post was not to address the issue of causality; it was simply to document what has been happening in the Nordic nations. But I close by noting that the pattern and timing of changes in the Nordic nations seems to fit the story that Jon has been developing (along with Jean Twenge) throughout this Substack and in his forthcoming book: childhood was rewired by technology in the late 2000s and early 2010s, with the biggest change happening in the early 2010s when teens traded in their flip phones for smartphones loaded with social media apps. It was only at that point that it became possible for teens to have the internet and platforms such as Instagram with them all the time; it was only at that point that teens could become ultra-heavy users, which meant more addiction, and far less time for in-person socializing.10

Do you have an alternative explanation? We would particularly welcome comments from researchers, parents, and teens in the Nordic nations. Were there other pan-Nordic changes in the early 2010s that can explain this pattern? Or have I missed any studies or datasets on Nordic mental health? Please add your ideas in the comments.

Zach Update Nov 27th, 2023:

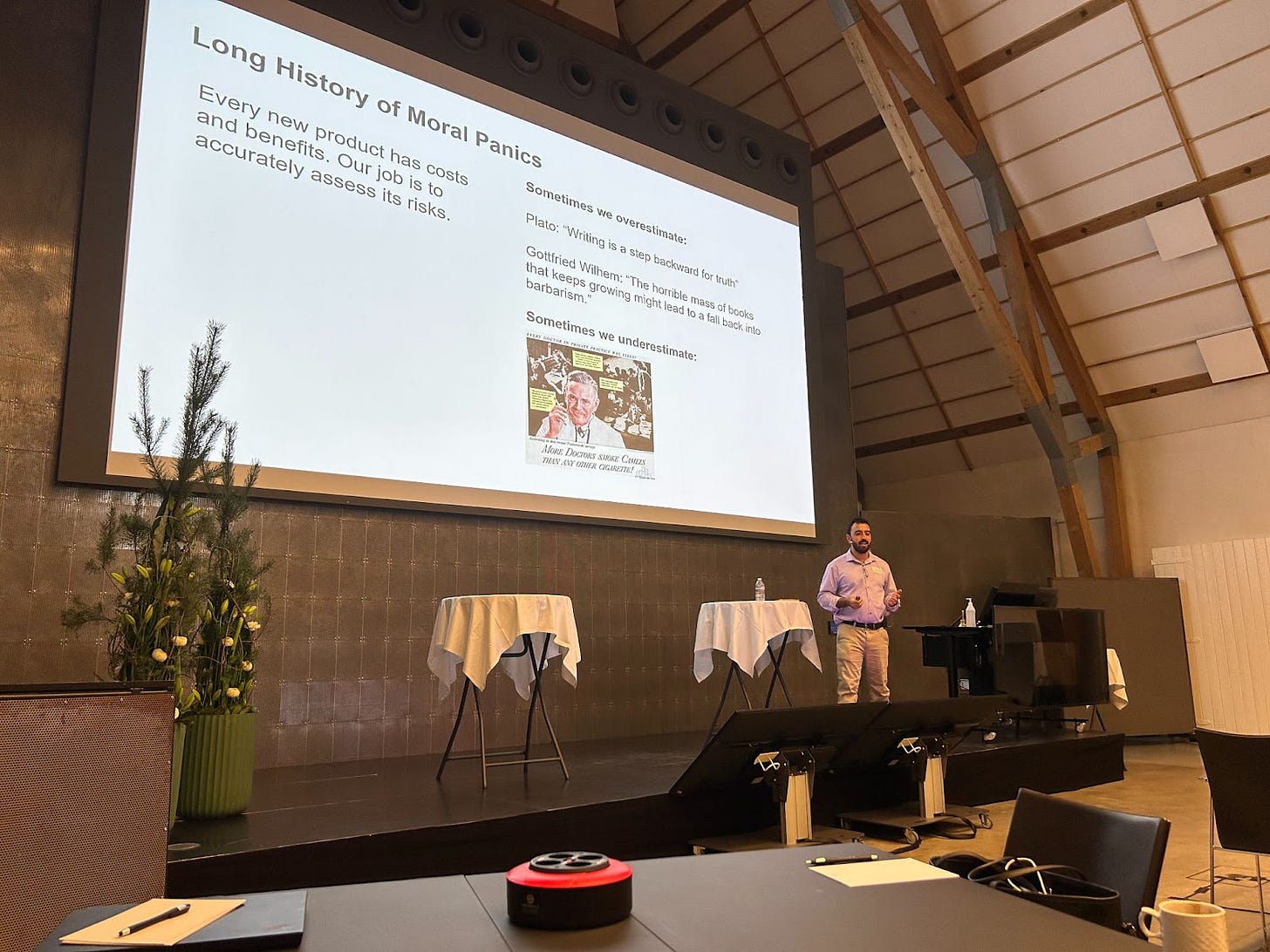

Two weeks ago, I traveled to Denmark to present Jon and my work on The Anxious Generation to a group of fifty or so leading Danish researchers, policymakers, clinicians, and academics. The conference, graciously run by the Tyrg Foundation and Novo Nordisk, spurred an enormous amount of discussion and debate. I came to Denmark with two big questions that I had been grappling with before the trip, and wanted to share what I have learned through my conversations:

Question #1

In my research on Danish youth mental health, I was surprised to learn that rates of self-harm hospitalizations among adolescent girls have followed a reverse-U-shaped pattern. Rates began to rise in the 2000s, hit a peak in the late 2000s, and have been falling ever since.

At the same time, other measures of Danish youth mental health have worsened since the early 2010s. Why have self-harm hospitalization rates declined among adolescents in Denmark, while self-reported rates of depression and anxiety are rising?

What I learned: I spoke with Dr. Britt Morthost, a leading Danish researcher who has published a number of articles on this exact question. Dr. Morthost explained that the most likely explanation for this change is that Denmark had taken steps to restrict access to common means of self-harm among youth, and this led to a rapid decline in self-harm hospitalizations.

In her 2020 study, Restriction of non-opioid analgesics sold over-the-counter in Denmark: A national study of the impact on poisonings, Dr. Morhost explains that Paracetamol is frequently used in deliberate self-harm incidents involving adolescents and young adult women. Thus, two legislative measures were taken in Denmark: (1) An 18-year age purchase restriction in 2011; (2) a pack size restriction for over-the-counter sales in 2013 (specifically, packages of no more than 20 tablets). Prior to the pack size restriction, as many as 300 tablets of paracetamol or Ibuprofen were available in pharmacies, while packages with 10 tablets of paracetamol (500 mg) or Ibuprofen (200 mg) were available in non-pharmacy outlets.

Her study looked into the impact of these two policies and found “an 18.5% reduction in the number of non-opioid analgesic poisonings per month following the pack size restriction. This is supported by reductions between 11% and 31% in emergency department visits and admissions due to paracetamol poisoning noted in previous studies.”

Danish Child and Adolescent Self-Harm Poisonings

But it wasn’t just that hospitalizations through paracetamol decreased and were replaced by other means of self-harm. Hospitalizations for self-harm fell across the board.

In addition to means reduction, Denmark also implemented additional suicide prevention strategies in 2007. Specifically, they began providing counseling, therapy, and practical support to persons with suicidal ideation or behavior nationwide at Suicide Prevention Clinics. It seems that the Danish health system has found means to mitigate the most severe outcomes of the mental health crisis, but is still struggling nonetheless.

Question 2

Has unsupervised play been declining in Denmark? What role does the loss of the “play-based childhood” have in Denmark?

What I learned: If there is one thing to know about the Danish people, it is that they love their bicycles. A 2022 report found that 81% of Danish adults own a bicycle, 51% bike at least once a week, and 21% ride almost every day.

However, I was fascinated to learn from one of the participants that rates of bicycle use among youth have been in decline—with parents less likely to have their young children ride on the bustling city streets. (Note that campaigns have been launched to try and address these changes. Also note that I have not been able to find any empirical studies looking at bicycle youth trends among youth). I was told that Denmark is often “ten years behind the United States.” It was concerning to hear that risky play may be in a period of decline in Denmark.

Importantly, I have been unable to find clear data on free play trends in Denmark. And of what I saw and learned, it still seems that there are many more opportunities for free and risky play than there is in the United States. I saw many young children playing on playgrounds designed with some risk, rather than complete safety, and learned of the many Forest schools around the country designed to connect children to nature and foster their innate antifragility.

What I also learned: Social trust has been declining almost everywhere, except Denmark.

One of the most hopeful and inspiring aspects of Danish culture is that despite the rapid technological and political changes of the last fifty years, they had higher social trust in 2010 than they did 30 years ago. This is completely unlike the United States and many other Anglo nations.

Social Trust Across Nations

Figure: The level of trust is the share of the population answering that “most people can be trusted” to the question, “Generally speaking, do you that think most people can be trusted or that you cannot be too careful in dealing with others” after removing “Don’t know” responses. Sources: World Values Survey 1981-2008 (WWS 2009) (data for Norway, Sweden, US, GB, France); European Values Study 1981-2008 (EVS 2011) (all countries); General Social Survey 1972-2010 (GSS 2011) (US); Politiske værdier i Danmark 1979 (Danish Data Archive 1981) (Denmark).

Note that the figure above ends in 2010. What about more recent data? A 2020 Pew Report found continued high rates of social trust (higher than any other nation surveyed), with 86% of Danish adults agreeing that “In general, people can be trusted.”

Additionally, the distinction of trust levels by age does not show the same stark differences as we see in other nations (though young people are lower than older Danes).

The necessity for social trust is crucial to overcome the many collective action problems we face today. This is especially true for parents who want to give their children more freedom and trust that they will be safe when they let them out into the world.

With the exception of Iceland, where rates are high across all female age groups except those above 60.

Items: “I feel like an outsider (or left out of things) at school,” “I make friends easily at school” (reverse-scored), “I feel like I belong at school” (reverse-scored), “I feel awkward and out of place in my school,” “Other students seem to like me” (reverse-scored), and “I feel lonely at school.”

See 1.1.3 of Nordic Adolescent Mood Disorders since 2010 to find the data, graphs, and statistical tests done regarding changes in loneliness and effects by gender.

Anxiety diagnoses plotted were of code F41 in the ICD-10. This includes general anxiety disorder, panic disorder, mixed anxiety and depressive disorder, other specified anxiety disorders, other mixed anxiety disorders, and unspecified anxiety disorder.

The indicator "anxiety, worry or anxiety" shows the percentage who answered the question: "Do you have one or some of the following problems or symptoms?" followed by, "anxiety or worry?" with the answer options: "No", "Yes, mild problems" and "Yes, severe problems.”

Depression and anxiety symptoms were measured using the Symptom Check List 90 (SCL-90). Respondents were asked whether they had experienced a number of symptoms of depressed mood and anxiety during the previous week. For symptoms of depressed mood and anxiety, a cut-off score was identified based on the top 5% at the first time point.

“The depression dimension of the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) was used to measure depressive symptoms. Participants rated ten items on depressed mood in the previous week on a four-point Likert scale (from 1 [almost never] to 4 [often]). A composite score of these items was created, with higher scores suggesting higher levels of depressive symptoms (range 10–40). To gauge changes in the severity of depressive symptoms over time, cutoff scores based on the top 5% at the first timepoint (ie, 2016) by age and gender were created and classified as high depressive symptoms.”

To be clear, the purpose of Figure 22 is not to equate major depression to psychological distress, but to show that trends in self-reported poor mental health follow the same basic pattern that we see in the Anglosphere. Additionally, it’s important to note that rates of teenage self-harm (of what I have found), on average, are much lower in the Nordic nations relative to the Anglosphere countries.

We have found trends showing that perceived academic pressure did increase in Nordic nations from 2012 to 2018, with the largest rise happening among girls. It is possible that academic pressure could explain or partially explain the rise in the Nordic nations, although it would not align with the academic pressure trends found in the United States, as Jean Twenge explained. Also, if the perception of increased pressure is larger in girls, that may be because girls were getting more anxious during that time period.

Wow just wow. This research you share and your clear explanations were so helpful. While I look at international research in all of my parenting work, I had not dug into the international research on teen mental health. In the US we often only think that things affect us and our children, but this is truly an international crisis.

Thank you for this detailed analysis. With the amassing data on the role that social media plays in the mental health deterioration of youth, it is high time to take action. We cannot expect swift action from government, policy makers, or school administrators. The action needs to start around the kitchen table, and parents must take the lead in serving as role models for their children if there is to be any hope. I will be publishing an essay this weekend 'From Feeding Moloch to 'Digital Minimalism' on my substack School of the Unconformed https://schooloftheunconformed.substack.com/, for those interested in taking concrete steps toward forming a digital detox community.