The Teen Mental Health Crisis is International, Part 1: The Anglosphere

Why did mental health fall off a cliff at the same time and in the same way in the USA, The UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand?

It is now widely accepted that an epidemic of mental illness began among American teens in the early 2010s. What caused it? Many commentators point to events in the USA around that time, such as a particularly horrific school shooting in 2012. But if the epidemic started in many nations at the same time, then such country-specific theories would not work. We’d need to find a global event or trend, and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis doesn’t match the timing at all, as Jean Twenge and I have shown.

In our 2018 book The Coddling of the American Mind, Greg Lukianoff and I presented evidence that the same trends were happening in Canada and the United Kingdom—not just the rise in depression and anxiety, but also the overprotection of children, the rise of “safetyism,” and the shouting down of speakers on university campuses when students deemed the speaker to be “harmful.” It seemed that all the Anglo nations were setting up their children for failure in the same ways at the same time.

In 2019 I went on a speaking tour of Australia and New Zealand (thanks to Think Inc) and discovered that the same trends were coming, more slowly, to the Southern hemisphere Anglo nations too. I then created two new collaborative review documents, one for Australia, and one for New Zealand, to gather all the empirical studies and journalistic accounts I could find.

In early 2020, just as COVID swept in, I hired Zach Rausch as a research assistant to help me handle these collaborative review docs. I connected with Zach, who was finishing his master’s degree in Psychological Science at SUNY New Paltz, after reading his blog post about his research related to The Coddling. Zach and I created many more collaborative review docs for many more countries and topics, which you can find (and add to) on this page.

In 2021, as I was beginning to work on the Babel project, I told Zach that it was urgent that we figure out just how international the mental illness epidemic was. Is it just happening in the five countries of what is sometimes called The Anglosphere? Is it all Western countries? Is it happening everywhere? Go figure it out and report back to me.

The rest of this post is Part 1 of Zach’s report, in his voice. I think his findings are momentous and should cause an immediate global rethinking of what children need to have a healthy childhood, and what obstacles to development arrived around the globe around 2012.

— Jon Haidt

(Addendum April 19th: Zach published his second post on international mental health trends. The post explores trends in the five Nordic Nations: You can read the report here).

When Jon first asked me to figure out whether adolescent mental health had collapsed around the globe after 2012, I thought he was crazy. The task felt impossible and beyond what I thought I could accomplish. But it was precisely this kind of work that I aspired to do. I set aside my doubt, put my head down, and gathered every relevant study I could find on adolescent mental health trends across the globe. In a series of posts, I will share with you what I have found so far. I address the Anglosphere today. In future posts, I’ll show what I have learned about Scandinavia and other developed nations and what I have learned from five international surveys, each with data from dozens of nations. There is much more to be done, especially beyond Western countries.

The short answer to Jon’s question is: Teen mental health plummeted across the Western world in the early 2010s, particularly for girls and particularly in the least religious and most individualistic nations. The longer answer begins below and will continue in parts 2 and 3.

What Happened to Adolescents in the Five Anglosphere Countries?

As Jon mentioned in the introduction to this post, he and Greg Lukianoff had already found evidence that the mental health crisis was occurring in Canada, the UK, and the USA. But it has been more than four years since the publication of The Coddling of the American Mind, and we now have access to a lot more data, so let me run through the five countries.

1. The USA

In two previous posts of the After Babel Substack, Jon has shown the rise of mental illness among American adolescents since 2010. Therefore, I won’t cover the United States in much detail. However, I include a few figures to provide a baseline for the countries we explore in the rest of this post. For each country, I try to show at least one graph or study on mood disorders (anxiety and/or depression), which is usually self-reported, and one on something related to self-harm or psychiatric hospitalization, which is usually not based on self-reports from teens. (Note that I defer the discussion of suicide rates to a future post. You can find data and graphs about suicide rates in each of the Collaborative Review Docs that I link to.)

Figure 1 shows the percentage of US teens since 2004 who reported having a major depressive episode in the last year.

Figure 1. Percent of teens with Major Depression in the last year. NSDUH data, see section 1.1.2 of the Adolescent mood disorders collaborative review doc.

As you can see, there was no sign of a problem before 2010, and by 2015 a depression epidemic was in full force. Today, more than one in four American girls (ages 12-17) report having a major depressive episode in the last year. And more than one in eight boys said the same.

Figure 2 provides behavioral (non-self-report) data on the number per 100,000 teens admitted yearly to hospitals because they harmed themselves, primarily by cutting.

Figure 2. Emergency department visits for self-harm, younger teens (ages 10-14), CDC data. See section 2.1.1 of the Adolescent mood disorders collaborative review doc.

Young teenage girls went to the emergency department for self-harm in 2020 at just about three times the rate they were in 2010. We see similar but slightly less steep trends among the 15-19-year-old girls (we also see this same gendered pattern in self-poisoning).

Here’s one additional graph to show that the rise in mental health issues was concentrated in young people—it was not happening across the board to all age groups:

Figure 3. Percent US Anxiety Prevalence. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

To summarize, four trends emerged in the data from the USA, which we will call the “basic pattern.” They include:

A) A substantial increase in adolescent anxiety and depression rates begins in the early 2010s.

B) A substantial increase in adolescent self-harm rates or psychiatric hospitalizations begins in the early 2010s.

C) The increases are larger for girls than for boys (in absolute terms).

D) The increases are larger for Gen Z than for older generations (in absolute terms).

Note that there are two ways to calculate increases. We can measure an increase in absolute terms, e.g., a rise from 5% to 15% of teens with a diagnosis is a ten percentage-point increase, or we can report it in relative terms, e.g., a rise from 5% to 15% is a 300% increase, relative to the anchor point. Both are important. From a utilitarian or public health point of view, we care more about the absolute increase, for it tells us the number of people affected. From a psychological research point of view, we also care about the relative increase since a large relative increase may alert us that something is changing for that group, even if its illness rate only moves from 2.1% to 4.3%. We decided to report the relative changes on our graphs since that is hard to calculate by eye. For example, as shown in Figure 1, the absolute increase from 2010 to 2021 was much larger for girls (17.3%) than for boys (7.1%), and that jumps out at you as soon as you look at the graph. However, the relative increase was slightly larger for boys (161%) than for girls (145%), which tells us that whatever is happening, it’s also affecting boys quite a lot.

2. Canada

With this basic pattern in mind, let’s move north to see how Canadian teens are doing. Jon and I include all of the studies we could find on Canadian youth in an open-source Google Doc titled “The Coddling of the Canadian Mind? A Collaborative Review.” If you know of other studies to add or want to learn more, please check it out.

The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), one of Canada’s most extensive nationwide surveys, collects national data bi-annually on various health-related measures. Using CCHS data, I re-graphed a few key mental health figures.

Figure 4 shows the percentage of Canadian males who described their mental health by choosing either “Excellent” or “Very Good.” Between 2003 and 2012, young men (ages 15-30) rated their mental health better than the two older groups, reaching 78% in 2009. However, within a few years, the percentage fell to 66%, becoming the age group with the lowest percentage of “excellent or very good” mental health.

Figure 4. Excellent or very good mental health, Canadian males. Canadian Community Health Survey (2003-2019). See section 1.3.2 of The Coddling of the Canadian Mind? A Collaborative Review.1

The change for females is more acute. Figure 5 shows the same pattern as the males, except that the youngest females dropped from 76.5% in 2009 to 54% in 2019, far lower than every other age group. As in the USA, the mental health of young Canadian females fell off a cliff in the 2010s. Also, as in the USA, the decline is large for Gen Z, and there is no decline for Canadians over the age of 47.

Figure 5. Excellent or very good mental health, Canadian women. Canadian Community Health Survey (2003-2019). See section 1.3.2 of The Coddling of the Canadian Mind? A Collaborative Review.

Self-report studies are important—we should listen to what people say about their own mental health. But changes over time could also reflect factors other than actual increases in mental illness, such as “concept creep” and changing trends in the desirability of having a diagnosis.2 Figure 6 shows data from the Canadian National Ambulatory Care Reporting System, plotting the rate per 100,000 Ontarian teens who went to the emergency department for harming themselves.

Figure 6. Emergency department visits for self-harm, Ontarian teens (Ages 13-17), Canadian National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS) data, graphed by Gardner et al. (2019), and re-graphed in 1.3.3 of The Coddling of the Canadian Mind? A Collaborative Review.

Just like in the United States, there has been an increase in self-harm hospitalizations, with a highly gendered nature. Since 2010, there has been a 138% increase in self-harm hospitalization for 13-17-year-old girls (from a low of 294.0 per 100,000 teens in 2010 to a high of 701.6 per 100,000 in 2017). The boys show an increase too, but from a much lower baseline, and there is no spike around 2012. Again, the pattern and timing are very similar to the USA: no sign of a problem before 2010, and then something terrible happens to Canadian teens in the early 2010s, especially to the girls.

Overall, Canada also shares the basic pattern. Although we do not have specific changes in rates of anxiety and depression, we see a significant decline in mental well-being among young Canadians. The changes in well-being and self-harm are larger for girls than for boys, in both absolute and relative terms. And the changes in well-being were much larger for the youngest cohort than for the older ones.

3. The United Kingdom

Because Jon and Greg had been studying the UK along with the US, all of the studies on teenage mental health trends in the UK were included in the original collaborative review doc, “Adolescent Mood Disorders Since 2010: A Collaborative Review.”

An essential UK data source, the United Kingdom National Health Survey, examined trends among 11- to 15-year-old English boys and girls for anxiety and depressive disorders at 3 points (1999, 2004, 2017).

Figure 7. Trends among 11- to 15-year-old English boys and girls for anxiety disorders and depressive disorders at 3 points in time (1999, 2004, 2017). (Graphed by Jean Twenge. We can’t tell where the elbow is since we only have data from 3 specific years.) See 1.3.3 in Adolescent Mood Disorders Since 2010.

Figure 7 shows that from 1999 to 2004, depression rates were steady for girls, while anxiety rates began to increase. For boys, anxiety was steady, while depression rates decreased. However, from 2004 to 2017, we see substantially larger increases in both mood disorders for girls and large spikes in anxiety for boys.

The most recent update of the UK National Health Survey (2021) did not include the same items on anxiety and depression. However, from 2017 to 2021, the researchers did find that rates of probable mental disorders among 11-16-year-old girls increased by 38.5%, from 14.3% to 19.8%. For boys, rates increased by 26.8%, from 12.3% to 15.6%.

Because the UK National Health survey looked at just three points in time, we can’t know when the increase began between 2004 and 2017. Fortunately, we can get better temporal resolution from a second study which took measurements annually, The Good Childhood Report, which presents data from Understanding Society: UK Household Longitudinal Study, UK's most comprehensive long-term national survey on child subjective well-being. As shown in Figure 8, the average happiness scores between boys and girls were no different in 2009. However, after 2009, the girls' rate began to drop, with an acceleration after 2013. The boys' rate dropped too, although the drop started later (after 2014) and was not quite as sharp.

Figure 8. Trends in children’s happiness with different aspects of life by gender, UK, 2009-10 to 2019-20, graphed in The Good Childhood Report (2022)—data from Understanding Society survey. See 1.3.4 of Adolescent Mood Disorders Since 2010. See p. 52 of the doc for trends before 2009. Happiness scores increased for girls from 1996-2008, while boys' rates rose in the late 90s, fell in the first few years of the 2000s, and then rose again around 2005.

Figure 9 shows one of the most sudden spikes in self-harm I’ve seen in any of the datasets I’ve looked at. In 2011, 13-16-year-old girls had a rate of 688.5 per 100,000. Within two years, that number had jumped to 1235 per 100,000 (a 79.4% increase). This graph confirms something we see in the American data repeatedly: something big seems to have happened to girls around 2012.

Figure 9. UK Teens, Self-harm rates per 100,000. Aurum and GOLD datasets of the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). See 1.3.6 in Adolescent Mood Disorders Since 2010, from Cybulski, Ashcroft, Carr, Garg, Chew-Graham, Kapur, & Webb (2021). Regraphed by Zach Rausch. [NOTE: The original figure said these data were of self-harm hospitalizations. This was misleading. These data represent changes in the number of recorded self-harm episodes identified through primary care records, rather than hospital admissions. Thanks to Louis Appelby for noting this error.]

As this post is already so long, I won’t dive into the data on the various nations within the UK, but the trends are very similar. The Scottish government recently published a report (study 1.5.4.1) detailing their concern about the mental health decline of teenage girls in their country since 2010. These disturbing trends are also happening in Wales (study 1.5.4.4).

We don’t have a separate document for Ireland, but every study I’ve found indicates that Irish youth are going through the same struggles (studies 1.5.4.2 and 1.5.4.3) as those in the UK.

So, to recap: The basic pattern emerges in the UK: Rates of depression, anxiety, and self-harm have risen since 2010, especially among girls. The girls always had larger increases in absolute terms, although on two graphs (figures 7 and 9), the boys had larger increases in relative terms. I have not yet found data allowing cross-generational comparisons, so that is still an open question.

Let’s now take a look at Australia and New Zealand.

4. Australia

You can view all of the studies we found on mental health trends in Australia in our document titled “The Coddling of the Australian Mind? A Collaborative Review.”

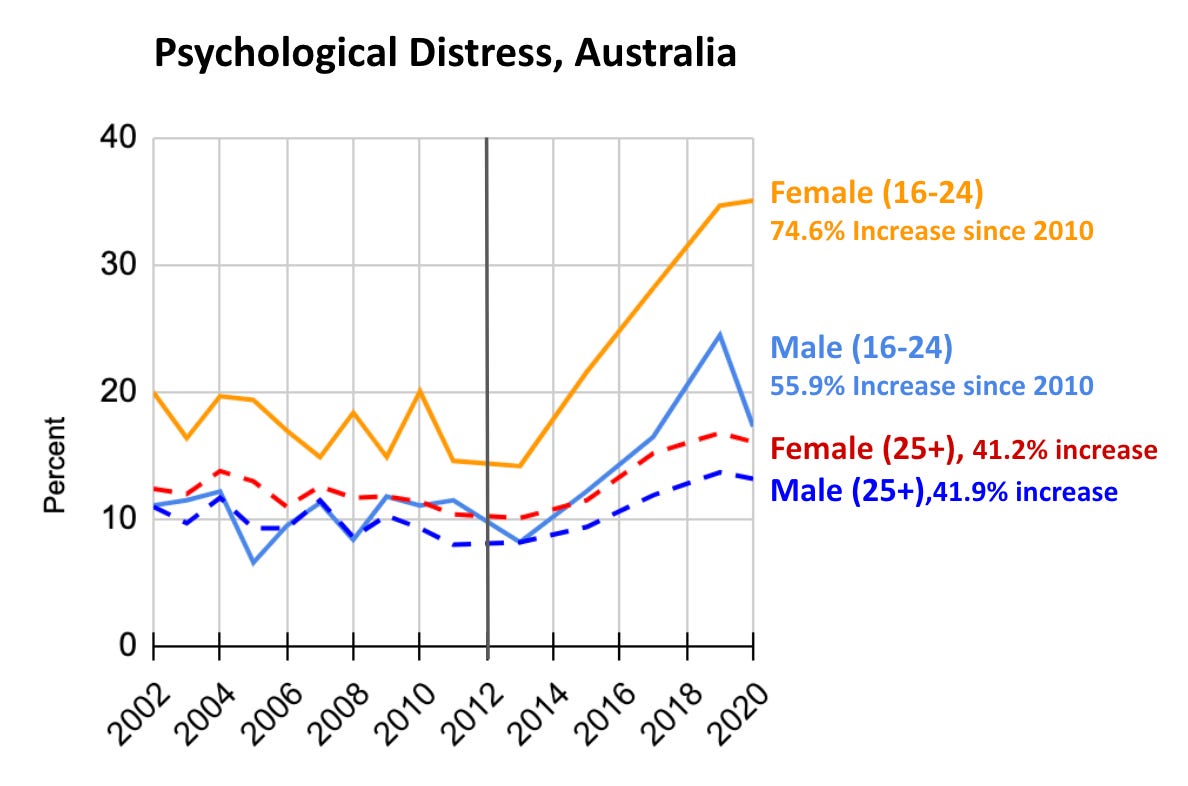

One of Australia’s most extensive health surveys comes from Australia’s Health, an 18-year-running flagship report involving thousands of Australians across the continent. Figure 10 illustrates the changes in the percentage of Australian youth and adults reporting high or very high psychological distress between 2002 and 2020. Before 2012, rates among the four age/gender groups remained generally steady. In 2014, this began to change. The percentage of young females (16-24) who reported high or very high psychological distress grew from 14.2% in 2013 to 35.1% in 2020.

Figure 10. Persons aged 16+ reporting high or very high psychological distress by age group and sex, 2002 to 2020. Australia's Health Snapshots 2022: Mental Health of Young Australians (2022). Data can be downloaded here. See 1.3.4 in The Coddling of the Australian Mind?

A similar pattern emerges in psychiatric emergency department visits, also tracked by Australia’s Health (Figure 11). There is little variation among age groups between 2007 and 2011. However, around 2012, hospitalization among 12-24-year-old girls and women began rising, from 558 per 100,000 in 2010 to 1012 per 100,000 in 2020, an 81% relative increase.

Figure 11. Overnight admitted mental health hospitalization rate (per 100,000 population) with specialized care, by age group and sex, 2006–07 to 2019–20. Australia's Health Snapshots 2022: Mental Health of Young Australians (2022). See section 1.3.4 of The Coddling of the Australian Mind?

Regarding self-harm rates, Figure 12 illustrates that the only age group that has had increases in self-harm hospitalizations since 2010 are the youngest girls, those ages 15-19 and 20-24. All of the older age groups show declines in self-harm rates.

Figure 12. Female self-harm hospitalizations (per 100,000 population) by age group, 2009-2020. Data from 2019–20 National Hospital Morbidity Database—Intentional self-harm hospitalizations. (see additional data here) Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. See section 1.3.9 of The Coddling of the Australian Mind?

Numerous other datasets in Australia support these general findings. For example, intentional poisoning exposure calls rose most rapidly for girls aged 15 to 19. Figure 13 reveals that the spike began in 2012. The study does not provide the precise number of incidents per year by age group and gender, so, I am unable to provide the exact percent change since 2010, however it is clearly up by more than 100% for girls aged 15-19.

Figure 13. Trends in intentional self-poisoning, ages 5–19 years, 2006-2016. Rates per 100,000. See 1.3.14 in The Coddling of the Australian Mind? Graph created by Cairns, Karanges, Wong, Brown, Robinson, Pearson, Dawson, & Buckley (2019), with text added by Zach Rausch.

The researchers found that “[the] effect was driven by increased poisonings in those born after 1997, suggesting a birth cohort effect. Females outnumbered males 3:1.” In other words, Australia’s Gen Z girls suddenly started poisoning themselves in much larger numbers in 2012.

In sum, Australia, like the US, UK, and Canada, fits the basic pattern. Rates of self-harm, psychological distress, overnight psychiatric hospitalization, and self-poisoning have all increased since the early 2010s, especially for girls and for Gen Z. (We note that self-harm hospitalizations for 15-19-year-old girls have declined since 2018—this will be an important trend to keep track of).

5. New Zealand

You can view all of the studies we found on mental health trends in New Zealand in our document titled The Coddling of the Kiwi Mind? A Collaborative Review.

The increase in self-reported anxiety and depression in New Zealand is among the steepest across all of the Anglo countries. Figure 14, with data from the New Zealand Ministry of Health, shows that in 2007, the percentage of 15-24-year-old males and females who said they had been given an anxiety diagnosis was approximately 3%. By 2020, the percentage of young females with an anxiety diagnosis had grown to 24.8% (a 259% increase compared to 2011). Males also rose to 9% in 2020 (a 131% increase).

These increases are so large, and the starting numbers are so low (just 3% of girls had an anxiety diagnosis in 2007?) that we suspect that this graph shows, in part, changing diagnostic criteria and greater awareness of anxiety. We do not believe that the underlying rates of anxiety disorders increased as quickly as the lines in Figure 11 suggest. Nonetheless, given what we are seeing in all of the Anglosphere countries, and given the self-harm data below, we believe that much or most of the rise is real. In any case, in 2007, only one in 30 girls thought she had an anxiety disorder; by 2020, it was one in four.

Figure 14. “Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have an anxiety disorder? This includes panic attacks, phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder?” New Zealand Ministry of Health, New Zealand Health Survey 2020. See 1.3.1 in The Coddling of the Kiwi Mind? Note that the survey was not conducted between 2008-2010, so we compared 2020 data with 2011.

When we compare across age groups, we find that the youngest age group (ages 15-24) had the lowest rates of anxiety in 2007 (2.6%), and by 2020, they had the highest rates among all age groups (16.3%, a 328.8% increase since 2011).

Figure 15. Percentage of New Zealanders with an anxiety diagnosis by age group. New Zealand Ministry of Health, New Zealand Health Survey 2020. See 1.3.1 in The Coddling of the Kiwi Mind? Note that the survey was not conducted between 2008-2010.

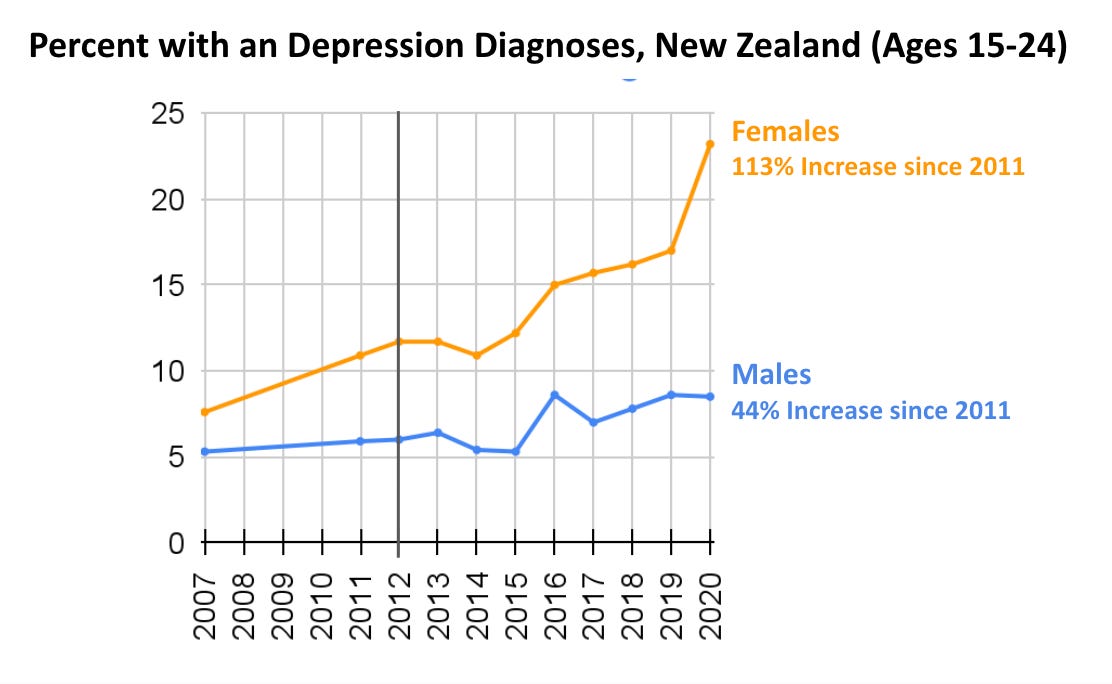

We see a similar pattern for depression (Figure 16), with low rates at the beginning of the 2000s but a steep rise in the second half of the 2010s, particularly for girls.

Figure 16. “Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have depression?” New Zealand Ministry of Health, New Zealand Health Survey 2020. See 1.3.1 in The Coddling of the Kiwi Mind? Note that the survey was not conducted between 2008-2010.

The age distributions for depression also map similarly to anxiety, except that the sharpest rise for the youngest cohort happened in 2020 (see 1.3.1 of The Coddling of the Kiwi Mind).

In another study, using a series of cross-sectional surveys between 2001-2019 of secondary school students (mostly between the ages of 13-17), Kylie Sutcliffe and colleagues (2022) found that “after relative stability from 2001 to 2012, there were large declines in mental health to 2019.” Since 2012, the researchers found that the proportion of youth reporting “good well-being” decreased as depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts increased significantly. There was, as usual, a gendered effect, with girls showing steeper declines in mental well-being (as well as important variation by ethnic group, with worsening trends among Māori, Pacific, and Asian students).

To examine behavioral changes, I plotted the total number of discharges from public hospitals in New Zealand for intentional self-harm from 2005 to 2019 (Using data from the New Zealand Ministry of Health’s National Minimum Dataset).

Figure 17. Total public hospital discharges for intentional self-harm by age and sex, 2005-2019. Ministry of Health, New Zealand. Data from The Ministry of Health’s National Minimum Dataset (NMDS). See 1.3.6 in The Coddling of the Kiwi Mind?

These are total discharges, not rates per 100,000 population, so a small portion of the increase could reflect population increase. But that would not explain why—as in the other Anglo countries—the rise is far greater among girls than boys, and it is not linear—it accelerates in the early 2010s.

In sum, the basic pattern reappears in New Zealand: Depression, anxiety, and self-harm rates started rising around 2012, with girls and Gen Z hit the hardest.

6. Conclusion

In sum, all five Anglosphere countries exhibit the same basic pattern:3

A) A substantial increase in adolescent anxiety and depression rates begins in the early 2010s.

B) A substantial increase in adolescent self-harm rates or psychiatric hospitalizations begins in the early 2010s.

C) The increases are larger for girls than for boys (in absolute terms).

D) The increases are larger for Gen Z than for older generations (in absolute terms).

Why did this happen in the same way at the same time in five different countries? What could have affected girls around the English-speaking world so strongly and in such a synchronized way?

As discussed in previous posts and as Twenge et al. (2022) showed, it can’t be the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The timing of that event is exactly the opposite of what you’d expect, namely: the epidemic should have started in 2009 and then gotten progressively better after 2012 as the economy improved in the USA and other countries. In an earlier post, Jean Twenge showed that it can’t be caused by rising academic pressure either. And it certainly can’t be caused by the most popular theory we hear in the USA: school shootings and other stress-inducing events. Why would school shootings or active shooter drills implemented only in the USA lead to an immediate epidemic across the entire English-speaking world?4

At this point, there is only one theory we know of that can explain why the same thing happened to girls in so many countries at the same time: the rapid global movement from flip phones (where you can’t do social media) to smartphones and the phone-based childhood. The first smartphone with a front-facing camera (the iPhone 4) came out in 2010, just as teens were trading in their flip phones for smartphones in large numbers. (Few teens owned an iPhone in its first few years). Facebook bought Instagram in 2012, which gave the platform a huge boost in publicity and users. So 2012 was the first year that very large numbers of girls in the developed world were spending hours each day posting photos of themselves and scrolling through hundreds of carefully edited photos of other girls.

If you suddenly transform the social lives of girls, putting them onto platforms that prioritize social comparison and performance, platforms where we know that heavy users are three times more likely to be depressed than light users, might that have some impact on the mental health of girls around the world? We think so, but if anyone can offer another explanation that fits the graphs we’ve shown in this post, we’d love to hear it.

This concludes the first part of my report. In Part 2, I’ll examine the Scandinavian countries. In Part 3, I’ll examine studies that collected evidence from multiple countries, mostly in Europe. In later posts, I’ll examine the limited data we have from non-Western nations. To give you a sneak preview, there are cultural variations within the West, and the Anglosphere was hit a bit harder than other regions. Whatever it was that changed about childhood in the early 2010s, it took the greatest toll on teens in the most individualistic nations.

Please tune in next week, and subscribe to the After Babel Substack if you have not already done so. (It’s free.)

Appendix: The Collaborative Review Documents

Here is the list of open-source collaborative review documents that Jon and I curate to track the mental illness epidemic around the globe. These documents are the foundation of my report.

Adolescent Mood Disorders Since 2010: A Collaborative Review. This document collects and organizes dozens of published studies documenting changes in adolescent mental health in the USA and UK in the 21st century.

Global Adolescent Mental Health Since 2010 A Collaborative Review.

European Adolescent Mood Disorders Since 2010 A Collaborative Review

The Coddling of the Japanese Mind? A Collaborative Review (Russell Kabir of Hiroshima University leads this doc)

The Coddling of the Latin American Mind? A Collaborative Review (Just beginning)

Jon and I have also created many more collaborative review docs while we work on the Babel project, including the docs we’ll use to report on the importance of play, the transformation of boys’ lives, and the effects of social media on democracy. We keep all of our collaborative review docs on this page: jonathanhaidt.com/reviews.5

Excellent or very good self-perceived general mental health: Respondents answered excellent or very good to the question, “In general, would you say your mental health is... ?”

Many studies have also found that self-report studies are at risk of social-desirability bias and several other biases and limitations. But these considerations can’t explain why Gen Z girls changed en mass around the world around 2012.

We are just missing proof of anxiety and depression rates going up in Canada, and of Gen Z having larger increases in anxiety/depression in the UK.

This is not to say that perceptions of educational pressure or school shootings do not affect youth mental health. Instead, it is to say that these explanations do not line up with why teenage mental health collapsed in so many countries at the same time and in the same way.

Thanks to everyone who has helped support me with this post, particularly Jon, and Nicole Kitten.

I am just back from Slovakia where I ditched the women's conference I was there for and instead sat on the sidewalk and listened to people, as I started doing in San Francisco 8 years ago for Sidewalk Talk. And my second day listening only high schoolers sat down and talked. Not a representative sample because they self selected to come to talk to me, were out of the house at a street food market, but they were one generation out of communist rule. So they had a focus that was about thriving rather than social comparison. And that felt marked to me.

But I am write this as a psychotherapist getting ready to go into a day of sessions after another shooting of young school age kids. And I know it will be a topic of conversation. I am readying a paper by psychoanalytically oriented therapists here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/10.1080/15289168.2023.2167045 And what they highlight that I want to bring in is loneliness as an add on to safetyism and social comparison. And I don't mean run-of-the-mill loneliness but existential terrifying loneliness. This paper suggests teens are being incredibly let down, by us grown ups and authority figures. We have left them to their own devices (pun intended) as a kind of existential abandonment and have not demonstrated any true capacity to help them hold the complexity of their terrifying feelings. We are bubble wrapping them instead of sitting in the muck with them. We are ourselves lack the skills to regulate our own feelings and instead polarize. What signals are we giving teens that the grownups can help them? My teen sons love calling everyone "Boomer" and I hear it is a thumbing the nose at the grown ups who are to blame. They are both angry at the grown ups and also simultaneously need us to act like grown ups, I think. Not by bubble wrapping them but by sitting in the feelings, setting good boundaries and tending human connection as value.

I read "The Coddling" early last year. It opened my eyes surely, but also confirmed something I'd already seen happening in my classroom (I'm now a retired high school teacher). I saw before my eyes a new addiction emerge -- the addiction to smart phones, specifically social media ... especially Instagram and TikTok.

So Dr. Haidt et. al. have seen the correlation with overall teen mental health (i.e. depression, anxiety, self-harm).

I'd be most curious to see if the exponential rise in gender dysphoria correspondes with the mental health data. In 2005, one in 2000 adolescents identified as trans. Now I've seen figures as high as one in five. That's a 2,000 percent rise in gender dysphoria. 2000 percent!

I'd like to see data analysis on the meteoric climb in trans identity, which seems to correspond directly to Dr. Haidt's et. al. research on mental illness.