What We Learned in 2023 About Gen Z’s Mental Health Crisis

Nine posts from After Babel tell the story

We launched the After Babel Substack eleven months ago, on Feb 1, 2023. We’ll have a post next February reflecting on our first year and looking ahead to our second. In this post, we highlight a few of our 31 posts that readers seemed to enjoy most, and that we believe are the most essential readings for those following this Substack.

The central question animating the After Babel Substack is this: Why does it feel like everything has been going haywire since the early 2010s, and what role does digital technology play in causing this social and epistemic chaos? We explore the chaos in two primary domains: adolescent mental health (which has been our focus this year, as we worked on The Anxious Generation), and liberal democracy (which will become increasingly important in late 2024, as we begin to work on the second part of the Babel project, a book tentatively titled Life After Babel: Adapting to a world we can no longer share).

The main line of our work so far can be summarized like this: We have shown that there is an adolescent mental health crisis and it was caused primarily by the rapid rewiring of childhood in the early 2010s, from play-based to phone-based. It hit many countries at the same time and it is hitting boys as well as girls, although with substantial gender differences.

Here is that main line in five posts, with a figure from each post:

This post frames the research debate and then summarizes the empirical evidence showing that heavy social media usage is a major cause, not just a correlate, of adolescent mental illness and suffering. (I also wrote a response to skeptics who critiqued this post.)

Figure 1. Percent of UK adolescents with “clinically relevant depressive symptoms” by hours per weekday of social media use. Haidt and Twenge created this graph from the data given in Table 2 of Kelly, Zilanawala, Booker, & Sacker (2019).

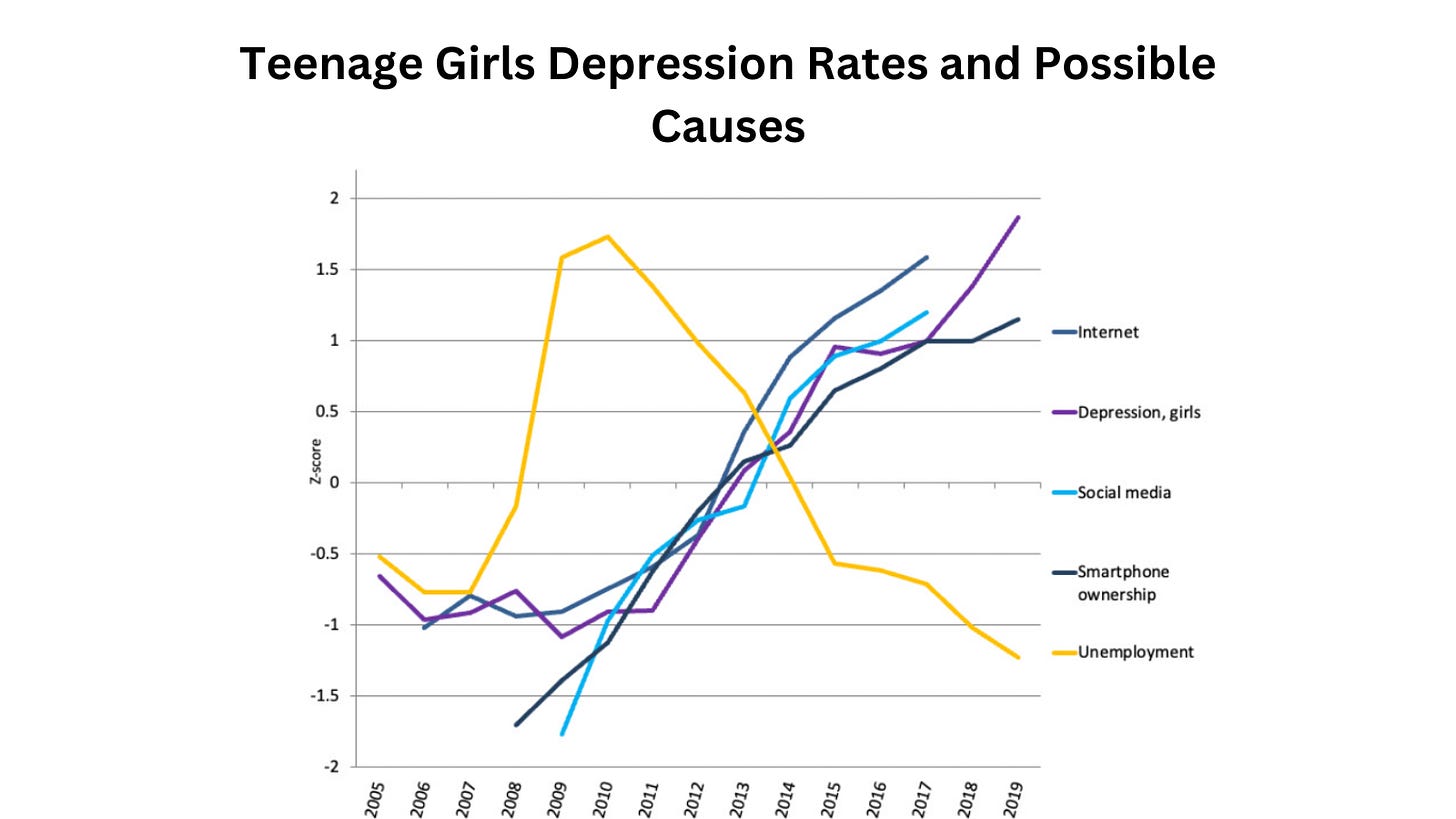

Here are 13 Other Explanations for the Adolescent Mental Health Crisis. None of them Work. By Jean Twenge

Jean Twenge, who was among the first to diagnose the problem in 2017, raises 13 alternative theories that we often hear and shows why they don’t fit the facts. They certainly can’t explain why the crisis hit so many countries in the years around 2013. Figure 2 shows Twenge’s response to alternative #4, that it was caused by the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. It wasn’t:

Figure 2. Technology adoption, teen depression, and national unemployment, 2006-2019. Sources: National Survey of Drug Use and Health, Monitoring the Future, Pew Research Center, Bureau of Labor Statistics. See also Figure 6.39 in Generations.

The Teen Mental Illness Epidemic is International, Part 1: The Anglosphere. By Zach Rausch and Jon Haidt

This is Zach’s first post in a series exploring the crucial question: Did the adolescent mental health crisis just arise in the U.S., which would guide us to investigate causes within American society? Or did it happen in many other countries at the same time, which would point us to causes with transnational reach, such as digital technology? The answer so far: It hit big in countries that are wealthy and individualistic, such as all five Anglosphere nations. Part 2 shows the same trends in the five Nordic nations. A subsequent post shows that the international problems go beyond depression and anxiety—Gen Z girls’ suicide rates are up across the Anglosphere. (Zach is currently working on a post showing that the worsening trends are widespread across Western Europe).

Figure 3. Since 2010, rates of self-harm episodes have increased for adolescents in all five Anglosphere countries, especially for girls. For data on all sources, and larger versions of the graphs, see Rausch and Haidt (2023).

This post picks up the analysis offered in The Coddling of the American Mind, whose subtitle is “How good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure.” The post shows how three very bad ideas were nurtured on Tumblr, around 2013, and then escaped into progressive online communities (and ultimately into progressive real-world communities such as university campuses), leading to a sharp rise in signs of depression, anxiety, and hopelessness that was most pronounced in young women on the left. Just as Greg Lukianoff had predicted, these ideas amounted to performing “reverse CBT” on those who embraced them.

Figure 4. Self-derogation scale, averaging four items from the Monitoring the Future study, e.g., “Sometimes I think I am no good at all,” and “I feel that my life is not very useful.” The scale runs from 1 (strongly disagree with each statement) to 5 (strongly agree).

Why I am Increasingly Worried About Boys, Too. By Jon Haidt

If you only look at published studies on social media and mental health, you’ll conclude that this is mostly a girl problem. Girls use social media more than boys and are more affected by it. But as Zach assembled all the research we could find about boys’ mental health, we found that boys are suffering just as much as girls, though in different ways. Boys’ sense of meaning and purpose collapsed as they retreated from the ever less appealing real world into an ever more immersive and addictive virtual world of video games, porn, social media, and online forums.

Figure 5. Percent of U.S. 12th graders who agreed with the statement: “People like me don’t have much of a chance at a successful life.” Source: Monitoring the Future 1977-2021, 2-Year Buckets, Weighted).

In addition to the main line of how digital technologies have reshaped childhood, we’d like to call your attention to posts in four related plot lines:

The first is that the rise of the “phone-based childhood” is only half of the story we tell in The Anxious Generation. The other half is the loss of the “play-based childhood.” Nobody has done more to call attention to the necessity of free play for healthy development than Peter Gray (who is a co-founder, with Lenore Skenazy and Jon, of LetGrow.org):

The second complementary line is a series called “Voices of Gen Z.” We have been looking for members of Gen Z who might critique our work and make a positive case for the phone-based childhood. We have found hardly any, as Eli George showed here. So, we have shifted to seeking out talented Gen Z writers who can tell the story of their generation from the inside. See for example:

Algorithms Hijacked My Generation. I Fear for Gen Alpha. By Freya India, and see also Do You Know Where Your Kids Go Every Day? By Rikki Schlott.

The third line is Solutions to the Mental Health Crisis. There are solutions, they are powerful, and they cost almost no money. The catch is that the big ones all require collective action. The best place to begin collective action is in schools, where the leadership has a duty to shape the culture. The easiest way to improve the culture of a school so that it promotes mental health, learning, and inclusion is to go phone free. Jon makes the case here:

The Case for Phone-Free Schools. By Jon Haidt

The fourth and final plot line is about how digital technology has had massive unintended effects on institutions and group dynamics. As Jon argued in a 2022 Atlantic essay, social media has made politically homogeneous groups become “structurally stupid”1 because everyone is afraid of being attacked by the extreme wing. Jon has been speaking and writing since 2011 about the dangers to universities of losing their viewpoint diversity; political orthodoxy is incompatible with the search for truth. In the age of social media, orthodoxy quickly descends into mob dynamics and a quasi-religious group cohesion obtained by hating a common enemy. In the final essay we recommend, Jon applies the analysis of “common enemy identity politics” from Chapter 3 of The Coddling to explain the shocking explosion of overt antisemitism on so many elite college campuses since October 7:

Why Antisemitism Sprouted So Quickly on Campus. By Jon Haidt

Thanks for joining us in 2023 on this journey to figure out what happened in the early 2010s—and what we can do to turn things around. We started this Substack in order to work out our ideas and pressure-test the story we were developing. Comments and criticisms from readers have been crucial for helping us find weaknesses and make The Anxious Generation more accurate and ultimately more impactful. Our goal is to start an international movement to roll back the phone-based childhood.

If you like what we’re doing here, please forward this post to friends, pre-order the book, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription if you have not already done so. We’ll have a lot more for you in 2024, especially after the March 26 publication of The Anxious Generation!

— Jon and Zach

Structural stupidity is what happens within a group or organization when dissent is punished and self-censorship increases. Stupid ideas are not challenged if they fit with the dominant ideology, so before long, a group of very smart individuals start behaving as if they were stupid.

I'm a father, grandfather, former journalist, P.R. professional and teacher (14 years, now retired), and currently a reborn writer also on Substack. My longevity (68 years old) and personal and professional life put me in direct view of the issues Haidt, Twenge, Lukianoff, Gray, et. al. have researched and published. In other words, I've seen in real life and real time the destructive behaviors and consequences in young people that their data reflect.

As a teacher I saw what the phones did to my classroom and how it captured my students' most valuable asset: their attention. I saw how adolescent social and learning growth went from free play in the 20th century but moved indoors with the advent of smartphones and social media in the late 2000s and early 2010s. I saw first hand the damaging effects of young people's retreat into social isolation.

It concerns me greatly. I often write about the plight of boys and men in my Quoth the Maven newsletter on Substack (https://jimgeschke.substack.com/p/the-politics-of-boys-and-men). I've seen the problems and am looking at viable answers and, more importantly, how these answers may translate into public policy.

Dr. Haidt writes about banning phones from schools during school hours. A great start. But what else? How can policy influence parenting and curtailment of isolationism and resultant despair of young people? I'm open to anyone's input and hope to write more about this critical issue.

To start 2024 on a hopefully positive note: reading the posts on here about the loss of independence and constant supervision of children inspired me and my wife to let our 9yo go to the shop nearby unaccompanied for the first time.

And, honestly? I hated it, at first. It’s not just children that are anxious compared to earlier generations. But now it seems like second nature and our child is more confident and happy at getting a little independence. And I would credit this substack for getting our family over that initial anxiety.