The Algorithm Next Door

How local digital platforms like Nextdoor and Facebook are fraying the fabric of neighborhood trust — and what we can build instead.

Introduction from Zach Rausch and Jon Haidt:

From cars to air conditioning, television to social media feeds, one cost of modern life has been the way it makes it ever more comfortable to sit alone in our living rooms or cars. It makes us need our neighbors less, which means we know them less and trust them less. The rise of cable TV, microcasting, and finally social media has also fed people a steady diet of stories showing the worst of human nature. This growing isolation, combined with a growing feeling of threat (even during the long period when crime rates were dropping), is a major reason why Americans stopped letting their children out by the late 1990s, as we have discussed in other posts in this series. If we want to restore a play-based childhood, we need to understand the reasons for its demise.

Today’s piece illuminates these issues through a story about a birthday party, a neighborhood app, and a boy who just wants to play outside. It explores how the fragmentation of community has accelerated with the rise of social media, making parents more fearful of one another and neighborhoods more disconnected. The essay shows that some of the very platforms marketed as ways to make communities safer — such as Nextdoor — have ended up amplifying fear, fueling the decline of social trust.

The post is written by Deepti Doshi, who co-directs New_ Public along with Eli Pariser, author of The Filter Bubble. New_ Public is a nonprofit Research and Development lab reimagining social media, with a focus on creating digital public spaces that connect people, embrace pluralism, and build community. The best way to follow along is their Substack newsletter.

— Zach and Jon

The Algorithm Next Door

By Deepti Doshi

Recently, we had a birthday party for my nine-year-old son Aiden. A pack of thirteen boys careened towards the little field around the corner from us to play a Nerf flag football game he made up.

However, not long after they left our front porch, one of the boys, Liam, came back to our house. “My mom says I can’t go unsupervised,” he said. Not knowing what else to do, my husband accompanied Liam back to the field, so he could rejoin the fun.

Liam's mother is my friend Caitlin. I know that Caitlin isn’t intentionally trying to punish Liam, she’s just scared. (I’ve changed both their names.)

Caitlin will often text me a horrific screenshot from her Instagram feed, or from Nextdoor, the neighborhood platform used by as many as one third of American households. These feeds seemingly deliver proof of Caitlin’s greatest fears: somewhere nearby, a child is in danger.

What is she supposed to think when a headline about a missing child from a nearby elementary school rises to the top of her feed?

And yet, what she’s seeing is not actually our lived experience: Our city — Berkeley, CA — is not dangerous. Like many towns, cities, and neighborhoods around the country, we saw some kinds of crime increase during the pandemic, and decline more recently. My neighborhood within Berkeley is particularly safe: only a few non-violent crimes were reported on nearby streets in the last month — not bad for an urban college town. Unfortunately, Nextdoor can make anywhere seem dangerous. What Caitlin sees on her phone is a warped version of our area, mediated by Nextdoor’s money-making algorithm. Isolated incidents from nearby areas are highlighted and made to seem like an epidemic of crime.

This phenomenon is not unique to social media and engagement-based algorithms: cable television and its associated 24/7 news cycles in the 1980s and ‘90s played a key role in amplifying public fears around “stranger danger” and child abductions. It has long been a truism that “if it bleeds, it leads,” on local news.

But social media is different in one important respect: TV producers do not have access to a firehose of data to custom-tailor their programming to each viewer. Whereas now, courtesy of algorithms, we each have a personalized feed or For You Page to scare the hell out of us.

Researchers in Australia have found that increased frequency of crime exposure on locality-based social media, including Nextdoor, is correlated with perceptions of neighborhood crime, even after controlling for different local crime rates. A meta-analysis also shows that social media use is related to crime and fear.

I feel empathy for Caitlin, and all parents who are afraid of what might happen to their kids. Terrible things do sometimes happen. But it’s crucial, for the sake of our children, to put our fears in perspective. We must understand the dynamics of our local information ecosystems and regain our own agency to do what's right for our kids.

For me, this highlights an important issue, tangential to those explored in The Anxious Generation: the effects of social media and smartphones on the parents of kids and teens. Other social platforms, including the local digital spaces we rarely think about in the context of “social media,” like Nextdoor neighborhoods and Facebook groups, are making parents afraid.

The Unintentional Business Model is Fear

The stakes are so much greater than one boy, Liam, needing a chaperone to play with the other boys at my son’s birthday party. It’s about a generation of Liams, who aren’t exploring their independence, cultivating friendships, and building self-confidence in their own neighborhoods.

If you don’t know your neighbors, everyone on the block is a stranger and potential threat. Kids like Liam stay inside to play video games, and when they get older, scroll social media. They become the data points of our loneliness epidemic.

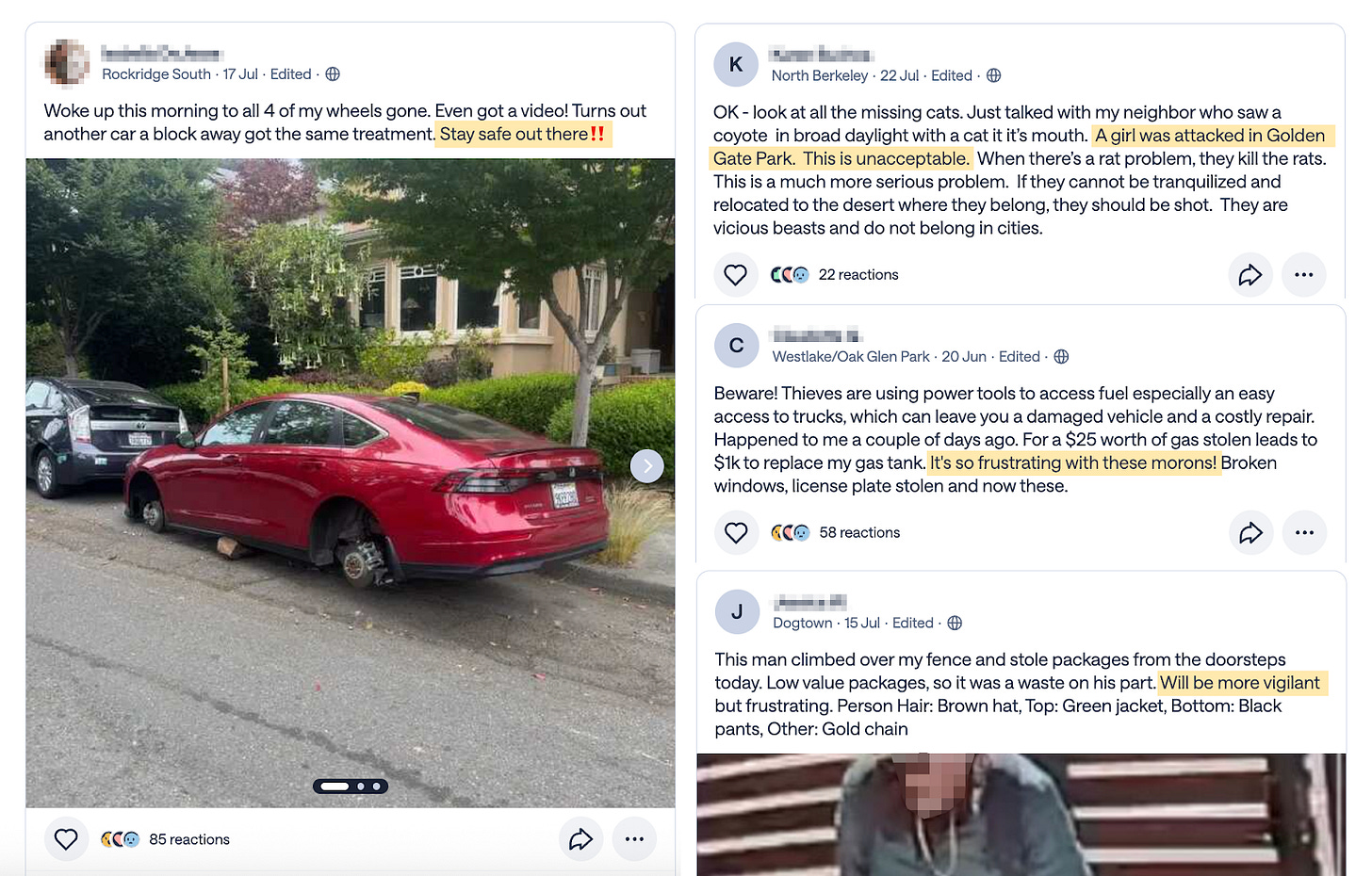

My friend Caitlin’s feeds are not at all unusual: Nextdoor’s best performing content is often the most incendiary content on the platform — the most violent and alarming incidents closest to you (which are often not even all that close, depending on how active your area is1).

If you’ve got an account, search your email for “Nextdoor” and you’re likely to see some of the worst things people are capable of and can experience: shootings, abandoned animals, car crashes, robberies. A small number of crime and safety posts are a huge source of engagement for Nextdoor, and engagement is vital to their stock price.

Nextdoor has just rolled out a redesign of their app, with a glossy new interface and some AI features. It’s too soon to say for sure, but at first glance, the fundamentals have remained the same: Nextdoor is in the business of fear.

And beyond Nextdoor, Facebook groups, WhatsApp groups, and email listservs are everywhere, in almost every community throughout the US. According to Pew, about half of US adults get local news and information from online forums and groups like these. Unfortunately, it’s not unusual for them to spill over into chaos, toxicity, and fearmongering.

I know, because I used to be on the inside: I was an exec at Facebook, working specifically on Groups. I saw firsthand how the incentives of these companies — to grow and drive engagement and sell ads — aren’t aligned with building the social cohesion and trust that parents and children need.

That’s — in part — why racist, terrified posts rack up views on Nextdoor, and Facebook group posts can inspire militia group activity in a rural community.

It’s Possible to Cultivate Safe Neighborhoods with Digital Spaces

But there are different, better ways for neighbors to connect online.

This is exactly what we’ve been researching and developing at New_ Public, a nonprofit I co-direct along with Eli Pariser. Back in 2012, Eli forecasted the divisive consequences of these algorithms in his book The Filter Bubble, and now they’re impossible to ignore.

We both believe that we can break the toxic cycle of platforms that profit off our fear. Let’s re-imagine social media as digital public spaces that build community trust and cohesion, in the same way that our libraries and parks do.

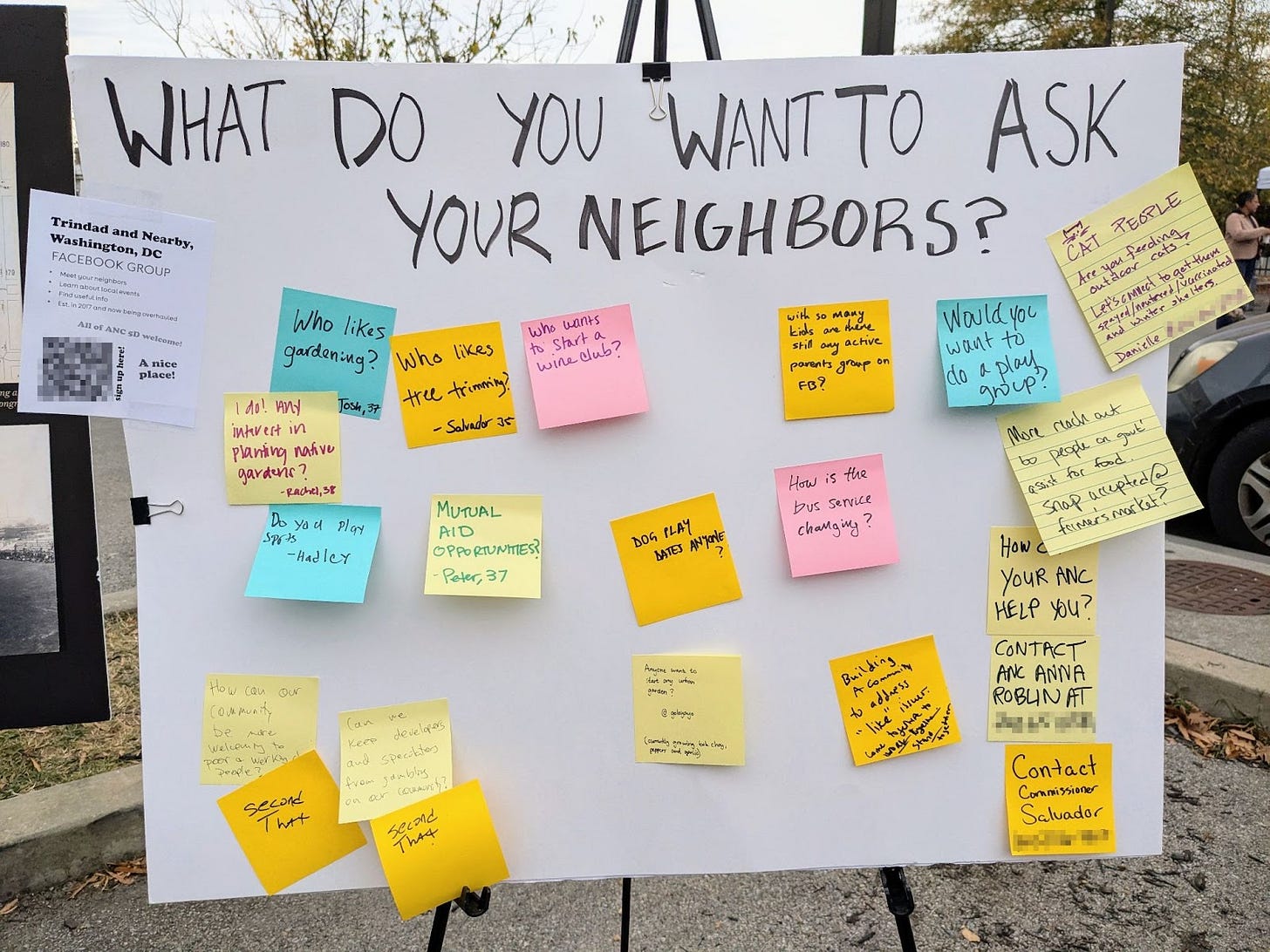

We need digital spaces that embody our Civic Signals: fourteen qualities of flourishing public spaces ranging from feeling safe and human to building bridges between groups.

And we’ve seen on some platforms that when developers and technologists design prosocial, public-spirited features and tools, so much is possible. Good design can help create the conditions to give our kids more freedom, and for parents to trust the community to look after them.

For example, Front Porch Forum is a homegrown, humanely-moderated network of local forums in Vermont. Over the course of two decades, FPF, a public benefit corporation, has worked with local advertisers to fund a sustainable network of over two hundred town-level forums. They collect no data from their users and only update once a day at most;reading FPF typically only takes five or ten minutes.

In our research, we found that people who spent more time on FPF learned more about their towns and became more civically engaged. Rather than making people afraid, FPF actually inspires neighbors to get to know each other and build social trust.

You can see the difference in the way people talk about FPF. Don Heise, who lives in Calais, a Vermont town with about 1600 people, told the Washington Post that FPF was “the glue that holds our community together.” Can you ever, in your wildest dreams, imagine someone saying that about Nextdoor?

Recently, our team at New_ Public has begun working on some Front Porch Forum-inspired community spaces of our own. We’re currently designing a platform that we aim to eventually scale throughout the US. Our work is guided by research into what works, along with our co-design process of building alongside the people who inhabit and care for these communities.

Throughout, we’re determined to keep a laser-focus on the needs of parents like Caitlin, who just wants her son to be safe, and Liam, who really needs to be able to run around with his friends and be free.

As a mom, I believe independence in public spaces is formative to childhood development and our development as an interdependent society. Kids should be running loose on the streets, eating impromptu dinners at a neighbor’s house, building lifelong relationships, and having so much fun in real life that screens can’t even compete.

Step up into Stewardship!

Building new technological tools will take time, but there is something everyone can do in the meantime: be a local community steward. Volunteer your time and energy where your neighbors already are: find a local Facebook group, subreddit, email listserv, or even a Nextdoor neighborhood, and offer to moderate. It’s never too late to introduce yourself to your neighbors — you probably have a lot in common!

If there aren’t any spaces like this near you, you might consider starting one. Or, you can sign up to get involved in what we’re building. Your care and attention are very likely to be appreciated by your neighbors.

We can shift from fear to trust, but we need to step into our bold ability to imagine — to imagine and build a new generation of healthy, useful, and fun digital spaces for connecting with our neighbors.

Nextdoor has a number of different ways to filter your feed, but the default — “For you” — prioritizes highly engaging content, including crime and safety posts. If you live in a Nextdoor Neighborhood with very little of this content, the algorithm will reach from further away to find posts for your feed. Depending where you live, this can be around the corner, or many miles away.

This information is so important these days. What often seems helpful to neighborhoods and communities can drive them apart. And this all due to Al and algorithms. It plays to the basest of animal instincts - fear and survival. Until humanity reaches a more profound and full consciousness, fear will rule as it is so easily stoked.

I love this post, and posts like it, and am in full agreement both about independence in neighborhoods being essential to child development, and also the fear mongering that has prevented it. HOWEVER, one thing I have not seen addressed in posts in articles, is that while statistics show that crime, etc is actually down, and so from a safety perspective there is not a reason to keep our kids indoors, what about cars/traffic. The number of cars on the road and the way people drive and the number of people looking down at phones while driving is an absolute nightmare where I live (suburban NJ). People will drive 50 plus on my 25 mph street, on the main street people speeding around a car stopped for a person crossing a street is CONSTANT, and you’ll frequently see 5 plus cars go through a light after it has changed. I know I’m not imagining these things. They are real and major issues here. And I don’t know how to reconcile them with wanting my kids to have independence. My oldest is 15 and thinking about him on the road in 2 years, where 90% of people seem to be looking down, is terrifying.