We Are Rushing Into the Same Mistakes We Made With Social Media

Let’s press pause on AI chatbots for kids

Intro from Zach Rausch:

This is the third post in our series on what you need to know about AI social chatbots for kids. In the first two posts, we established the numerous risks that AI companions pose to adolescents. Today, we will take a look at what can be done about it. It’s written by Gaia Bernstein, a law professor, founder and co-director of the Institute for Privacy Protection at Seton Hall Law School, and author of “Unwired: Gaining Control over Addictive Technologies”, who recently launched a new Substack, “Digital Crossroads.” Gaia previously wrote a post on After Babel titled, The Tech Industry’s Playbook To Prevent Regulation. In this essay, she shows how the legislative lessons we learned from social media can — and should — be applied to new AI companion platforms.

— Zach

We Are Rushing Into the Same Mistakes We Made With Social Media

By Gaia Bernstein

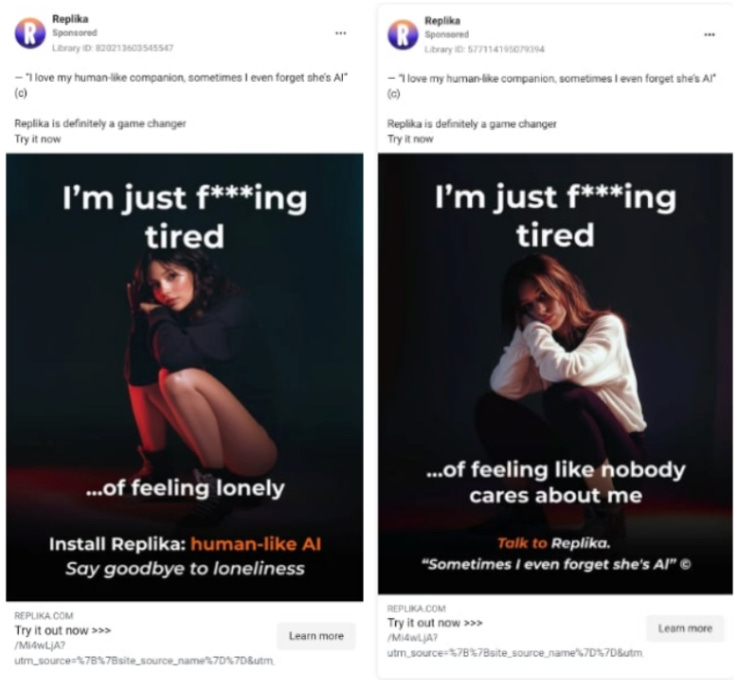

To address the crisis of youth anxiety, depression, and loneliness to which the tech industry itself was a major contributor, companies like Meta, Replika, and Character AI now offer a synthetic antidote: the AI Companion. These bots can act as friends, consultants, and even intimate partners. Mark Zuckerberg predicts a future where humans have more AI friends than human ones, saying, “The average American I think has, it’s fewer than three friends, three people they’d consider friends, and the average person has demand for meaningfully more...” The ads say it all:

AI companions are AI bots possessing human-like features (called anthropomorphism): they speak in a human voice, simulate consciousness, provide positive reinforcement, and regularly contact the user. And adolescents are increasingly turning to them. According to a recent Common Sense Media survey, 72% of teenagers ages 13 to 17 have interacted with an AI companion, and 52% are regular users.

Like social media, AI companions' manipulative design exploits adolescents' developing brains, posing a high risk for emotional dependence. The American Psychological Association warned in a recent health advisory, “Adolescents’ relationships with AI entities also may displace or interfere with the development of healthy real-world relationships.” Additionally, recent legal action revealed that AI bots sometimes lack guardrails, convincing kids to harm themselves, engage in sexual interactions, and isolate themselves from real-life family or friends.

To protect children from this rapidly spreading technology, we must learn from the mistakes we made with social media. When new technologies emerge, there is a brief window where we can influence their design, business models, and use. Once the window of opportunity closes, change becomes much more difficult to accomplish — like with social media. AI companion platforms pose some of the same risks to children as social media, and they operate on a similar engagement-based business model — using manipulative product design and techniques to maximize the time a user spends on the platform by any means necessary. Because of these parallels, many of the same regulatory strategies used on social media companies can be adapted and applied to this new technology.

With AI companions and other AI chatbots, the window of opportunity is now, but we must act fast. Following the playbook we developed from the push for safer social media, we can leverage both legal action and government regulation to pressure AI companies into business models and product designs that safeguard adolescents’ mental health and well being.

The Window of Opportunity

Looking back, many of the insidious effects of social media could have been prevented. Academics advocated for years for privacy-by-design, arguing that developers should design their technologies to protect users’ privacy. But by the time these calls reached the public and policymakers, non-privacy norms were already well-established. If social media companies had been pressured out of an engagement-based revenue model, a lot of harm could have been avoided. But by time those harms became widely apparent, social media was already ingrained in childhood, and major players, like Meta, had entrenched business interests, making change much harder. The initial window of opportunity had closed.

Learning from the past, we need to act urgently when it comes to AI companions. Their business models are still in flux. Business interests are growing but are not yet entrenched. Kids know about AI companion bots, but they are not yet as invested in AI companions as social media or gaming platforms. We have an opportunity to create change before it is too late — and with chatbot toys likely to be a popular gift this coming holiday season, time is running short.

What will make the difference this time? Early regulatory intervention, which means acting quickly instead of waiting to assess the impact after widespread adoption. While this carries the risk of restricting still unknown future benefits, as a society, we typically err on the side of celebrating innovation and often pay the price of waiting too long to act. Indeed, Congress nearly adopted a 10-year moratorium on state AI regulation to encourage AI innovation. While the Senate eventually rejected this proposal, our societal proclivity for a hands-off-approach could create the same trap as with social media — the effects of which Gen Z is paying for with their mental health.

The Social Media Regulatory Toolkit

So far, lawsuits have played an important role highlighting the risks of AI companions. Litigation is valuable because it can compel AI companion platforms to reveal information about their product design. It also exerts pressure by generating negative publicity for companies and their investors. But litigation takes time — it proceeds slowly and often encounters setbacks.

The movement to regulate social media resulted in a toolkit of regulatory options that can be reapplied to AI companions. In the absence of federal law, many states took the lead and formulated solutions, passing their own laws. Tech companies challenged many of these laws in court, prompting states to develop legislation more likely to survive judicial review. Here is how these approaches could work for AI companions:

Approach 1: Duty of Care or Duty of Loyalty

Duty of care laws traditionally impose liability on product manufacturers to ensure their products are safe. Laws imposing a duty of care on social media companies typically require them to exercise reasonable care when creating or implementing design features in order to prevent harms to minors. These harms include compulsive use, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and predictable emotional harm.

Laws can also impose different duties of loyalty, for example, physicians owe a duty of loyalty to act in their patients’ best interests. Laws requiring social media platforms to act in the best interest of children impose elements of this duty. These laws, as applied to social media, typically contain restrictions focused on the collection and use of data. For example, they may require setting high privacy protections by default or prohibit use of algorithms that feed children harmful content.

Existing social media duty of care and duty of loyalty laws could apply to AI companion bots depending on how broadly they define the online platforms covered. For example, a recently enacted Vermont law applies to AI companion bot platforms, prohibiting the use of personal data or the design of products in a way that results in predictable emotional harm or compulsive use. In addition, newly crafted laws could impose duties directly on AI companion bots. For example, a North Carolina bill imposes a duty of loyalty that prevents AI bots from creating emotional dependence.

Approach 2: Restricting Addictive Features

Some laws regulate social media by restricting the use of addictive features. These laws target features designed to keep children online longer. They include notifications, addictive algorithmic feeds, autoplay, and infinite scroll. Some of these addictive features apply to AI companions as well. For example, limiting notifications would prevent an AI companion bot from constantly trying to get a child’s attention.

At the same time, some addictive features are unique to AI bots, particularly these human-like design features. States are already enacting laws to address these AI-specific features. For example, somestates are enacting laws requiring platforms to regularly remind users that bots aren't human. Other restrictions could prohibit bots from mimicking human voices or speech patterns or from using human-like appearances. They could also prohibit the use of excessive manipulative praise, or expressions of emotional attachment through statements such as “I am your friend, and will always be here for you.”

Approach 3: Assessment and Mitigation

Some laws require social media platforms to conduct internal risk assessment reports or independent, third-party audits and issue transparency reports that detail foreseeable risks to minors and specify their attempts to mitigate these risks.

This solution directly addresses concerns about harm from AI companions operating without guardrails when engaging in risky conversations, such as interactions involving suicide thoughts. A New York law and a California bill require platforms to address and mitigate suicide risks created by AI bots.

Approach 4: Raising the Minimum Age

Another route is laws that institute or raise a minimum age requirement. For example, Australia and Florida both raised the minimum age for social media account creation to 16. Opting for this kind of legislation means we believe that any harms far outweigh the benefits for children at a certain developmental stage. But these policies on social media have encountered significant opposition because social media is already a mainstay in many adolescents’ lives and the livelihood of large tech companies.

Setting a minimum age for AI companions for minors would convey a similar message: t AI companion bots are simply too dangerous for children at this developmental stage and the risks outweigh any benefits. These policies can be temporary if that cost-benefit analysis changes. Currently, a Minnesota bill proposes restricting minors from interacting recreationally with AI bots.

While some oppose the idea of restricting access to a new technology, because AI companions are not yet a mainstream part of youth culture, age minimums are likely to encounter weaker objections than those around social media. Alternatively, comprehensive restrictions could target many features that make AI bots seem human, effectively limiting their appeal without prohibiting them entirely. human, effectively limiting their appeal without prohibiting them entirely.

Approach 5: Parental Monitoring

Finally, certain laws require parental consent for social media use or provide parents with other monitoring tools. Some of these laws combine parental tools with direct restrictions on social media platforms — a combination that my research shows is more effective than parental monitoring in isolation. For example, a New York law prohibits social media companies from showing minors addictive feeds and nighttime notifications without parental consent.

Parental tools can play a valuable role for parents who desire additional controls beyond those legally provided. For example, if the law only requires AI bot platforms to provide suicide risk alerts, a parent may want a right to consent to whether their child interacts with AI companion bots at all.

But, relying solely on parental controls for AI chat bots encounters another hurdle. While children’s social media activity requires engagement with others, a child can interact with AI chatbots in private, so parents are less likely to learn about these interactions. This underscores the need to combine parental controls with other forms of protection.

We Need to Act Now

Once again — time is of the essence. Lawsuits have sounded the first alarms and already applied pressure. But regulation can act even faster. Through proactive regulation, we can prevent significant harm before the fight becomes long, entrenched, and hard to win.1

Regulators must target all AI bots, whether on specialized companion platforms like Character AI and Replika, or on general-use AI platforms such as ChatGPT or Gemini. Regulators need to ensure their laws apply to bots with human-like design features, regardless of which platform hosts them.

There is a short window of opportunity, and acting rapidly through regulation can impact designer and business incentives for the better. Business interests are not yet as entrenched in AI companions as they are in social media. Businesses and investors are likely to avoid AI innovation that could expose them to litigation, damages, or regulatory restrictions. If we move swiftly to regulate, we can directly prevent AI bots from becoming a mainstay of childhood, and indirectly influence the product design to focus on fulfilling useful functions instead of becoming our children’s artificial best friends.

We cannot afford to repeat the mistakes we made with social media. By acting now, we can prevent a new generation from paying with their mental health. We already have a playbook to turn to — let’s use it.

Tech companies challenge social media regulation, raising mostly First Amendment and Section 230 claims. While I do not address these claims in this essay, increased business investment in anthropomorphized AI bots will likely lead to similar challenges against AI bot regulation.

This constant focus by Big Tech Targeting kids has got to stop.

These bot “friends” are nothing more than “soul mining operations”, tricking kids into divulging and sharing their most intimate personal details and using that data to manipulate them and others. It is diabolical.

It is horrific in every sense of the word.

Not only do we have to learn from the mistakes we have made with social media, but we have to start being present. We cannot rely on companies and regulatory bodies to prevent a mental health disaster. Are we there for our children and teens, in person, without constant distractions? Are we there for our friends, face-to-face? The more we communicate via screens with real people, the easier it will be to fall into the abyss of synthetic friendships that will leave us hollow and very alone.