Introduction from Jon Haidt:

Freya India is one of the most sensitive and perceptive Gen Z writers. She went through the social media maelstrom herself and now chronicles its effects on her generation. She writes widely, especially on her Substack, GIRLS.

Zach and I enjoy her writing so much that we invited her to join the core team at AnxiousGeneration.com. We’ve already published one of her essays: Algorithms Hijacked My Generation. I Fear For Gen Alpha. Now that she’s on our team, you can look forward to an essay from her each month as part of our series of “Voices of Gen Z.” Welcome, Freya!

There is a beautiful and melancholic word I like called anemoia. It means nostalgia for a time or a place one has never known.

This is a sentiment I often sense from my generation, Gen Z—especially in recent years. I see it in the YouTube videos of old concerts that get millions of views. I see it in our fascination with polaroids, vinyls, vintage cameras, and VHS tapes. And I see it in our reaction to gut-wrenching videos about how life has changed, like this short movie about dating that recently went viral:

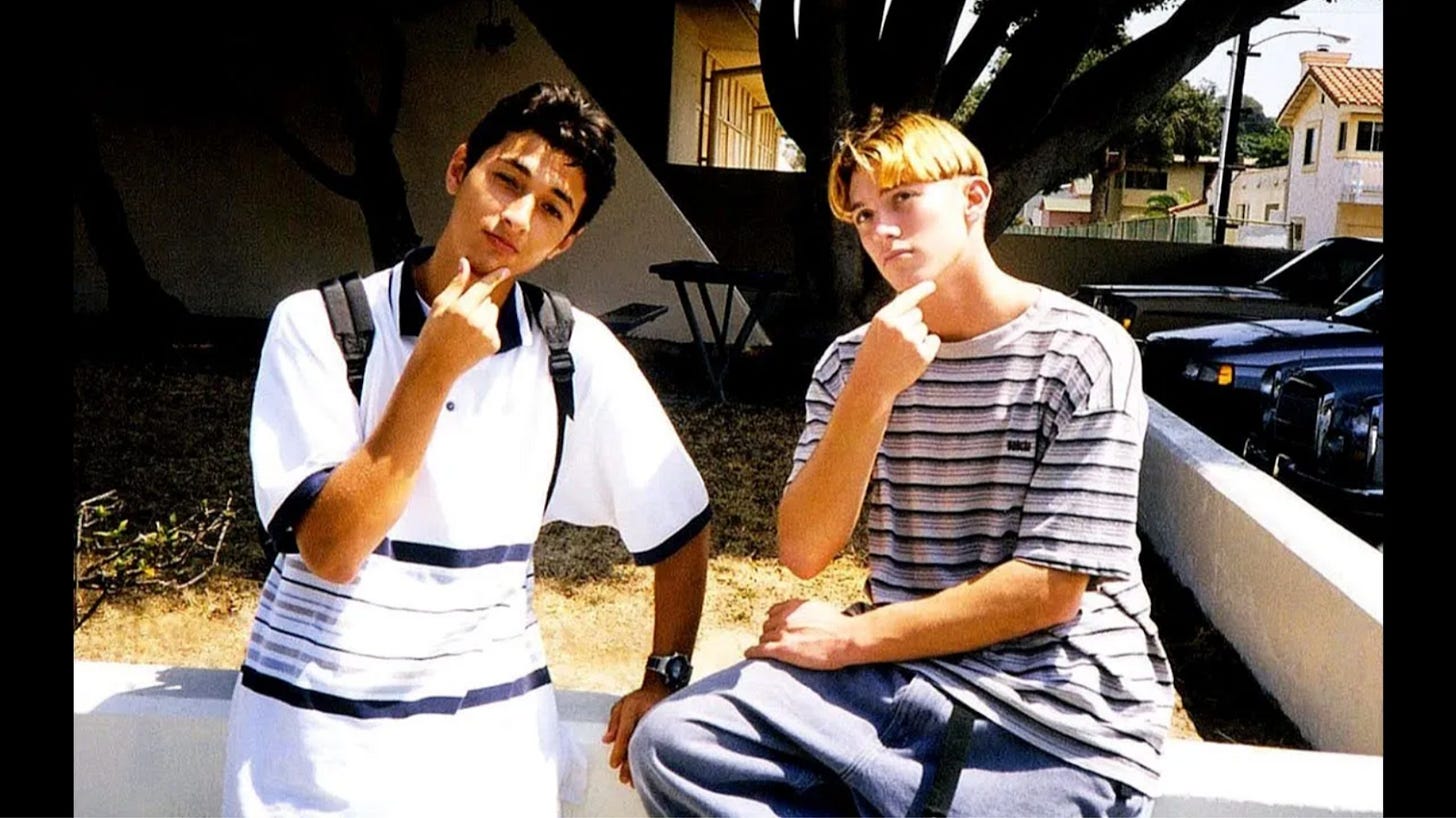

But perhaps the best example of anemoia is the popularity of ‘90s high school videos, like this one trending on TikTok. Or this one on YouTube, with millions of views, captioned “Phones? No. We had each other.”

This video has nearly 30,000 comments, some from Gen Xers nostalgic for their ‘90s youth—but many from Gen Z, aching for a world they never experienced. Older generations might dismiss this as teens wanting to be different and reject modern culture, as they often do. But the comments reveal something deeper:

“This feels nostalgic despite me not even existing during this time.”

“The whole concept of a real ‘childhood’ is completely out the window at this point in time and that’s extremely sad to me. Btw I’m 15, born in 2003.”

“I’m 20 years old so I wasn’t even conceived at the time of this video but it leaves me feeling empty. My highschool experience was nothing like this. I remember short bursts of people living in the moment but EVERYTHING revolved around our phones, Snapchat/Instagram status. It almost makes me angry because I’ve never had simple straight forward interaction as shown in this video. Even looking at people in the background, they are completely present and not buried in their phones. Everyone seemed a lot more social. I’m jealous of millennials/gen x, yall experienced a golden time to be young and free.”

“As someone who graduated in 2015 this looks like such a nice time. Not a phone in sight. People actually talking face-to-face. I wish I could have grew up in an era like this.”

“The Matrix came out that year. Now we live in it.”

There were hard times, of course—the ‘90s weren’t all bliss; no era is. But the world we inhabit now is so markedly different. New technologies cheapen and undermine every basic human value. Friendship, family, love, self-worth—all have been recast and commodified by the new digital world: by constant connectivity, by apps and algorithms, by increasingly solitary platforms and video games. I watch these ‘90s videos, and I have the overwhelming sense that something has been lost. Something communal, something joyous, something simple.

Of course, we have so many material comforts and conveniences now. I can follow the news all over the world, Google any statistic I want, write on Substack, and WhatsApp someone on the other side of the world. All for free. In a world like this, it’s easy to see why older generations might not understand why Gen Z is struggling to cope.

But God, that loss—that feeling. I am grieving something I never knew. I am grieving that giddy excitement over waiting for and playing a new vinyl for the first time, when now we instantly stream songs on YouTube, use Spotify with no waiting, and skip impatiently through new albums. I am grieving the anticipation of going to the movies, when all I’ve ever known is Netflix on demand and spoilers, and struggling to sit through a entire film. I am grieving simple joys—reading a magazine; playing a board game; hitting a swing-ball for hours—where now even split-screen TikToks, where two videos play at the same time, don’t satisfy our insatiable, miserable need to be entertained. I even have a sense of loss for experiencing tragic news––a moment in world history––without being drenched in endless opinions online. I am homesick for a time when something horrific happened in the world, and instead of immediately opening Twitter, people held each other. A time of more shared feeling, and less frantic analyzing. A time of being both disconnected but supremely connected.

But I never knew it. Maybe briefly, as a child. But most of us in Gen Z were given phones and tablets so early that we barely remember life before them. Most of us never knew falling in love without swiping and subscription models. We never knew having a first kiss without having watched PornHub first. We never knew flirting and romance before it became sending DMs or reacting to Snapchat stories with flame emojis. We never knew friendship before it became keeping up a Snapstreak or using each other like props to look popular on Instagram. And the freedom—we never felt the freedom to grow up clumsily; to be young and dumb and make stupid mistakes without fear of it being posted online. Or the freedom to be unavailable, to disconnect for a while without the pressure of Read Receipts and Last Active statuses. We never knew a childhood spent chasing experiences and risks and independence instead of chasing stupid likes on a screen. Never knew life without documenting and marketing and obsessively analyzing it as we went.

Now, the next generation? Gen Alpha? I can only imagine the loss they will feel. They are on track to never know friendship without AI chatbots, or learning without VR classrooms, or life without looking through a Vision Pro. They are being born into a world already anxious and atomised. My guess is that one day they will find family photo albums and hear stories about how their Millennial parents met and be hit with anemoia.

Maybe I’m naive. Maybe all generations look back with nostalgia. But my sense is they don’t do it for a time they never knew. They feel a longing for their youth; their childhood. My parents might flick through black-and-white photos and hear stories from my grandparents and feel intrigued, but not so much grief. I think there is something distinctly different and deserving of our attention about online forums filled with Zoomers wishing that they lived before social media. Wishing it didn’t exist. These are children grieving their youth while they are still children. These are teens mourning childhoods they wasted on the internet, writing laments such as “I know I’m still young (14F), and I have so many years to make up for that, but I can’t help but hate myself for those years I wasted doing nothing all day but go on my stupid phone.”

I think anemoia is partly why we’re seeing a rise in sales for flip phones in the United States, particularly among young people. I think that’s why Gen Z is moving away from dating apps. And it’s why, when Jonathan Haidt asked me to join his Free the Anxious Generation team, and his chief researcher Zach Rausch asked me to explain why I care about the movement, my first thought was to try and express this feeling—the anxiety of a phone-based world. The loneliness, yes, but also the grief. The loss. The feeling of wanting to be free from the only world we’ve ever known.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We can give future generations a real-world childhood. We can prioritize play. We can delay entry to social media platforms until at least 16. We can encourage young people to just hang out with each other, without supervision and without smartphones. We can take elements of childhood from previous eras and re-introduce them in modern life. But we have to remember what has been lost. When we are grieving record stores, mixtapes, old-school romance, and friends goofing around in ‘90s high schools, what are we actually grieving? Delayed gratification. Deeper connection. Play and fun. Risk and thrill. Life with less obsessive self-scrutiny. These are things we can reclaim—if we remember what they are worth and roll back the phone-based world that degraded them.

We have to start somewhere. I suppose what I’m asking for here is some sympathy and a little more grace. It’s easy to mock Gen Z and Gen Alpha for their soaring screen time, to roll your eyes at teenagers wasting their youth in their rooms, ruminating about themselves, and feeling hopeless about the future. But they are trying their best to keep up with a world so agonizingly different from any before it—and it is the only one they have ever known.

So please. Next time you cringe at Gen Z for not coping, for not feeling cut out for this world, remember how painful it is to think that the good times are over. Then imagine how much more painful it would be to realize you never knew them.

Postscript from Jon Haidt:

I am engaged in debates with other researchers about whether there is evidence that social media is causing harm to adolescents rather than—as some skeptics say—merely being correlated with harm (over and over again, in many countries). The debate is entirely about quantitative evidence from studies that measure time spent on social media, or that try to get young people to reduce their social media usage. But in the social sciences, qualitative evidence is an important kind of causal evidence. Freya is not just describing an accidental correlation. She is an eyewitness to the abduction of childhood, and in this essay, she brought us the eyewitness testimony of many others in her generation. Of course, we are then obligated to seek out voices on the other side—members of Gen Z who write essays or books asserting that smartphones and social media have improved their childhoods, their lives, or their mental health. We have done that in this essay by Eli George, in which he found almost nobody offering a defense (we are still looking for Gen Z’ers who disagree with us. Please send us essays or videos of your critiques). This is not just another groundless moral panic. Freya is bringing us a plea for help from young people caught in a collective action trap.

I don't ordinarily comment on Substack posts, but as a millennial, I just want to say: Freya, there are so many people older than you who understand and resonate with what you say here. Some may "cringe at Gen Z for not coping," but many others fully understand why you feel the way you do. It's unfair that Gen Zers couldn't enjoy screen-free childhoods. Your willingness to speak on this subject is a gift to Gen Alpha, who can still be spared much of that technocratic infection. And it's a gift to our society more broadly.

The good news is that embodied presence is always available to those who make the conscious choice to fight for it. And one of the glorious parts of adulthood is learning to recognise and prioritise the things you need to flourish—including freedom from screens. I hope that Gen Z increasingly finds that to be true in the coming years.

Thank you for sharing your perspective.

I got Instagram at 13 and just got off it just a couple months ago at 24. Having a baby daughter of my own made me see the sickness of pixelating your identity. I imagined going online as a teenager and being able to watch her life story unfold from day one through my social accounts—and I didn't want that for her. I want her to tell her own stories and hold onto her own memories and to own her own life. I want her to be able to be a joyous nobody. Undocumented and free. Because I didn't have that. I hope my gift to her at 18 will be zero search results on the internet for her name.