The Price of Mass Amusement

Prescient warnings from Neil Postman about the tradeoffs we make with new technologies

Intro from Jon Haidt:

As humanity gropes through this period of head-spinning technology-driven disruption, it is comforting and helpful to look back to the long ascent of electronic communications—from the telegraph through the telephone, radio, and television—and examine the social effects of those technologies. We began this exploration on After Babel in December, when we published Fordham University philosophy professor Nicholas Smyth’s “Smash The Technopoly!,” our first post on the great media theorists of the 20th century.

Smyth discussed the ideas of Marshall McLuhan and Neil Postman, with a focus on Postman’s book Technopoly. He summarized the central idea of that book like this:

In Technopoly, Postman distinguishes between a tool-using culture and a technopoly. All cultures have tools, but some cultures have moral resources necessary to constrain and direct the uses to which tools are put.

Postman gave the example of Samurai warriors, whose mastery of sword technology gave them extraordinary powers, which were held in check by a culture of honor.

But within a technopoly, the tool becomes the master. It takes on a life of its own, steamrolling over a great many prior moral convictions or constraints.

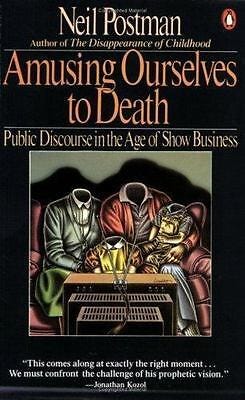

Today, we bring you an essay on what is probably Postman’s most influential book, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. In this book, Postman argues that the rise of television and its accompanying show-business norms brought about a widespread loss of both moral and intellectual resources, transforming American society from a technology-using culture to a technopoly in which our tools become our masters. If Postman was right—that television ushered in a technopoly—then this concern becomes even more pressing for social media today, and what is coming with AI.

Today’s essay comes from Andrew Trousdale, a young man I first met in 2019 when he was researching decision-making under Professor John Griffin at UVA. We met again in 2021 when he was studying positive psychology with Marty Seligman. I was impressed by his insights back then, so I was delighted when he enrolled last fall as a graduate student at New York University, to study human-computer interaction—and even more pleased when he signed up as a student for the graduate class I teach at NYU-Stern. We discussed our mutual interests and love of Neil Postman, and I invited Andrew to share the key ideas of Amusing Ourselves to Death to the readership of After Babel. Below, he guides us through the two big tradeoffs we made in the television age—choices we are now making again in the digital age. Like Smyth, Trousdale calls on us to understand—and then resist—the technopoly.

— Jon

In 1985, Neil Postman wrote Amusing Ourselves to Death, a book about television and its transformation of American culture. Thankfully, George Orwell’s dystopian visions from 1984 hadn’t come to pass. But Postman feared another dystopia: Aldous Huxley’s less famous Brave New World. He began the book by echoing Huxley’s warning:

People will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think. (p. xxi)

Looking around today at the mindless mobile games, endless social media feeds, and AI that thinks and writes for us, these warnings from Huxley and Postman seem more prescient than ever.

To understand Huxley’s warning, it helps to compare 1984 and Brave New World.

In 1984, Orwell feared blatant abuses of technology, especially exploitation, surveillance, and propaganda. The primary danger was powerful tools in oppressive hands. In Brave New World, Huxley focused on the most seductive uses of technology: convenience, pleasure, and amusement. The threat comes from within—technologies so gratifying that we willingly give up our capacity to lead valuable lives:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance… In 1984, Orwell added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we fear will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we desire will ruin us. (p. xxi-xxii)

Orwell’s vision is compelling. We can easily imagine authoritarian powers wielding advanced technology as a tool of control––because some authoritarian regimes do so today. There is a clear villain in these cases. Although citizens may be powerless to throw off such repressions, they maintain their sense of innocence and even moral superiority.

Huxley’s vision is subtler and harder to swallow. There’s no crushing oppressor, just gradual capitulation and surrender to amusing technologies. We are the danger to ourselves. We like the pleasure, the shortcuts, the distractions, so we don’t care how our technology degrades our minds, our relationships, and our culture.

Postman believed that for America, Huxley’s vision was the more relevant one. Amusing Ourselves to Death is about how TV, by the 1980s, was making Huxley’s fears come true. And, while Postman passed away in 2003, just a few months before the launch of Facebook, his work has just as much to teach us about the perils of modern tools of amusement, particularly social media.

Two Great Tradeoffs of Modern Media

In Amusing Ourselves to Death, Postman argues that television damaged American culture in two major ways: first, it undermined public discourse with a flood of fragmented and irrelevant information; and second, it demoralized us by turning amusement into a virtue.

Taking directly after his teacher Marshall McLuhan, Postman believed that the best way to grasp a society was to study its tools of communication. In his view, these tools don’t just reflect a culture; they actively shape it. Like McLuhan, Postman drew an important distinction between a tool’s content—the insight, drivel, propaganda, and poetry humans have produced in every age—and its form: how a technology works, how it structures information, and what it demands from users.

Though human expression has always ranged from the trivial or dishonest to the profound, the way we communicate has changed dramatically. When oration was dominant, knowledge had to be woven into memorable myths, proverbs, and songs. The advent of writing freed us from the limits of memory, allowing for more complex ideas that could be revised and expanded upon by others. By favoring different types of information and styles of thinking and interaction, new forms of communication technology gradually reshape cultural norms and values.

These changes in form were therefore essential for Postman. Though he cared about how people use technology, he was especially concerned with how technology changes the people who use it. Elsewhere he said: “a new technology does not add or subtract something. It changes everything.” (p. 18)1

When a new communication tool becomes widespread, society naturally embraces its most obvious benefits—often ignoring the hidden tradeoffs that subtly alter our psychology and culture.

With television, Postman saw two such tradeoffs linked to its dazzling capabilities. First, TV delivered instant, easily consumable information—a clear benefit linked to the hidden cost of degrading public discourse. Second, TV promised cheap, round-the-clock amusement—a seductive capability linked to the hidden cost of trivializing culture and elevating amusement to a priority.

These are the main effects of TV that Postman addresses in Amusing Ourselves to Death. His concerns about the price of instant information and mass entertainment apply as readily in the social media age. Let’s examine them more closely.

Tradeoff #1: The Price of Instant Information

Postman loved print—not out of nostalgia, but because he believed its inherent demands had virtuous effects on culture. Print is slow and effortful: writers must observe, reflect, and edit, while readers must grapple with nuance and complexity. These demands act as natural filters on the quality and coherence of information.

In the age of print, ideas were rooted in context—documented by people in particular places, grounded in what they had seen. As for the consumers of print, “reading was both their connection to and their model of the world. The printed page revealed the world, line by line, page by page, to be a serious, coherent place, capable of management by reason, and of improvement by logical and relevant criticism.” (p. 62) Through its form, print produced a culture of reasonable and disciplined thinking.

Then came electronic media—first the telegraph, then radio and television—which promised to transcend the limits of print. Their reach was instant and vast, decoupling information from time and place. And while writing and reading demand effort, speaking and listening come more easily.

But when information can be broadcast instantly to anyone, anywhere, with minimal effort to produce or consume, the nature of what gets transmitted changes. Postman argued that electronic communications

gave a form of legitimacy to the idea of context-free information; that is, to the idea that the value of information need not be tied to any function it might serve in social and political decision-making and action, but may attach merely to its novelty, interest, and curiosity. (p. 65)

By flooding us with attention-grabbing content condensed for rapid consumption, electronic media turned information into a stimulant.

The visual nature of the screen further degraded information:

Television gives us a conversation in images, not words. The emergence of the image-manager in the political arena and the concomitant decline of the speech writer attest to the fact that television demands a different kind of content from other media. (p. 7)

Though some people strive for quality and truth, screens naturally favor what’s catchy in 30 seconds, what’s pleasing to the eye, and what flatters our prejudices. These are the demands of show business, and they are in direct tension with the dissemination of high quality information. For, “if politics is like show business, then the idea is not to pursue excellence, clarity or honesty but to appear as if you are, which is another matter altogether.” (p. 126)

The effect?

Americans are the best entertained and quite likely the least well-informed people in the Western world. I say this in the face of the popular conceit that television, as a window to the world, has made Americans exceedingly well informed… what is happening here is that television is altering the meaning of ‘being informed’ by creating a species of information that might properly be called disinformation... misleading information—misplaced, irrelevant, fragmented, or superficial information—information that creates the illusion of knowing something but which in fact leads one away from knowing. In saying this, I do not mean to imply that television news deliberately aims to deprive Americans of a coherent, contextual understanding of their world. I mean to say that when news is packaged as entertainment, that is the inevitable result. (p. 106-107)

Substitute “television” for “social media” and Postman’s critique remains remarkably sharp. The rapid, hyperconnected flow of information brings real benefits. But look around: demagoguery and political theater, “flooding the zone with shit,” activists who barely understand their causes, and steadily declining trust in institutions. If we accept Postman’s view, these crises of truth and discourse stem in part from the form of the technology, which inherently favors instant, fragmented, and amusing information.

Tradeoff #2: The Price of Mass Amusement

The second great tradeoff is in the title: Amusing Ourselves to Death. The price of amusement, pursued with evermore technological efficiency, is death—whether spiritual or cultural.

Remember Postman’s notion that a new technology doesn’t just add something; it changes everything. As information technologies, TV and social media change what it means to be informed. As tools for mass amusement, they don’t just entertain; they turn everything they touch into entertainment.

Sesame Street was at least a well-intentioned idea: use TV for education. However:

We now know that Sesame Street encourages children to love school only if school is like Sesame Street. Which is to say, we now know that Sesame Street undermines what the traditional idea of schooling represents. Whereas a classroom is a place of social interaction, the space in front of a television set is a private preserve… Whereas school is centered on the development of language, television demands attention to images… Whereas in a classroom, fun is never more than a means to an end, on television it is the end in itself. (p. 143)

We couldn’t turn TV into education, but in trying, we created the expectation that education should be smooth, fun and, God forbid, never frustrating or boring.

When reality is prepared for the screen, it must be flattened, abbreviated, and dipped in sugar:

This is the lesson of all great television commercials: They provide a slogan, a symbol or a focus that creates for viewers a comprehensive and compelling image of themselves. In the shift from party politics to television politics, the same goal is sought. We are not permitted to know who is best at being President or Governor or Senator, but whose image is best in touching and soothing the deep reaches of our discontent. (p. 135)

In other words, the real significance of content on TV is secondary. What matters is how they make us feel.

This gets worse online. In social media culture, “my truth” (feelings without evidence) becomes the legitimate foundation for opinion. Of course! On a medium for amusement, the mood of the audience reigns supreme. Though gut emotions have always figured into politics, our most recent election was officially and unapologetically “vibes-based." Meanwhile, our masters of the universe are Twitter trolls and memelords. And our TikTok influencers turn natural disasters into nihilistic satire. We’re not just having more fun. We’re making important matters trivial. Amusement is the master virtue—everything must accommodate it.

And so, gradually, amusement becomes our default mode of engaging with the world:

Americans no longer talk to each other, they entertain each other. They do not exchange ideas; they exchange images. They do not argue with propositions; they argue with good looks, celebrities and commercials. (p. 92)

Postman perfectly anticipates Instagram culture—where an influencer's attractiveness passes for authority, and, even worse, where we perform for our friends, substituting authenticity with superficiality and validation. When these pseudo-social platforms come before real friendship, they drive us further apart from one another.

By transforming the world for pleasing consumption, we degrade its contents and demoralize ourselves. Nothing is truly sacred. Studying televangelism, Postman said, “I believe I am not mistaken in saying that Christianity is a demanding and serious religion. When it is delivered as easy and amusing, it is another kind of religion altogether.” (p. 121) Spirituality can’t be “gamified” and community can’t be downloaded from the app store. To be gratified by shortcuts is to be deprived.

That such technological pleasures and shortcuts are attractive, even irresistible, is what makes them dangerous according to Postman:

What Huxley teaches is that in the age of advanced technology, spiritual devastation is more likely to come from an enemy with a smiling face than from one whose countenance exudes suspicion and hate. In the Huxleyan prophecy, Big Brother does not watch us, by his choice. We watch him, by ours. There is no need for wardens or gates or Ministries of Truth. When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious public conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, a people become an audience and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; culture-death is a clear possibility. (p. 155-156)

The hidden price of mass amusement—once confined to our living rooms, now living in our pockets—is culture without substance, validity based on what feels good, and the willing surrender of our capacity for meaning.

What Would Postman Say Today?

Postman shows us how to understand a society by studying its tools of communication. His analysis is so prescient in part because TV and social media share two fundamental similarities—both deliver instant information and mass entertainment. But Postman adamantly opposed what he called “rear-view mirror” thinking: “the assumption that a new medium is merely an extension or amplification of an older one; that an automobile, for example, is only a fast horse, or an electric light a powerful candle.” (p. 83) There are doubtless many differences between television and social media (for instance, that the latter is always on and in our pockets, or that it hosts anonymous people and bots). Today, Postman would likely emphasize two fundamental differences.

The first is that we all have a camera now, and it points both ways. We are both the audience and the show. We embrace this technology because it meets our desire to share and be seen by others. But then the cameras and screens come between face-to-face interactions, eventually replacing them. For many now, our impulse during a great experience is not to enjoy it for ourselves, but to document it for others. The value of an experience is measured by our audience’s reception. This two-way camera is insidious: we fear surveillance yet we surveil ourselves; we fear judgment yet we invite it upon ourselves; we fear inauthenticity yet we reduce ourselves to images.

The second fundamental difference is algorithms. TV draws us in and shapes us. But compared to algorithmic media, it is generic. Algorithms morph content to us, drawing us in and changing us more thoroughly. The promise of personalization is seductive, but the cost is steep. By accommodating our preferences and prejudices, algorithms distort reality and distance us from each other. In doing so, they make us fragile and righteous. They drain our interest in the world. And in the end, the personalized amusement is only a means of capturing our attention: the more we consume from algorithms, the more they consume us.

TV created a willing audience for trivial shows. But at least we were in the audience together. On algorithmic social media, we are each a hooked audience of one, for a show that we struggle to understand or turn away from.

Algorithmic social media is more psychologically powerful than any technology Postman knew. But he had an optimistic streak that may still be appropriate today. He believed that “no medium is excessively dangerous if its users understand what its dangers are. It is not important that those who ask the questions arrive at my answers... asking of the questions is sufficient. To ask is to break the spell.” (p. 161)

The Anxious Generation movement has embraced Postman’s insights. There are profound psychological and social tradeoffs in the technologies we’ve welcomed for near limitless access to information, entertainment, and a (warped) sense of social connection. If you’re here reading at After Babel, you’ve probably felt the tradeoffs for yourself. The envy and judgment on Instagram. The compulsive scrolling. The sense of overwhelm. The hatred of strangers. The heartbreak of hooked children. Enough is enough.

On the precipice of the age of AI, now is the time to wake up. When we let algorithms represent the world to us, we give up our unique point of view. When we let them accommodate our preferences, we give up our tolerance for complexity. When we let them write for us, we give up thinking for ourselves. When we let them mediate our relationships, we give up genuine connection.

Postman asked that we question what our technologies truly cost us. To ask is to break the spell.

From Postman’s 1992 book Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology

Thank you, Andrew. This is a powerful conclusion: "When we let algorithms represent the world to us, we give up our unique point of view. When we let them accommodate our preferences, we give up our tolerance for complexity. When we let them write for us, we give up thinking for ourselves. When we let them mediate our relationships, we give up genuine connection."

As a species, we're delegating serendipity, chance, inspiration, rejection, and attachment to the machines. They become more while we become less.

Neil Postman is brilliant, and his work is more relevant than ever. Andrew discusses the cost of amusement, and I recently wrote about the other side of the equation: the opportunity costs of things we don't do while we are being amused.

https://open.substack.com/pub/technoskeptical/p/things-undone