Smash The Technopoly!

Neil Postman, Marshall McLuhan, and The Anxious Generation

Introduction from Jon Haidt:

In 2014, I felt something change. To use some old movie metaphors, it was like a disturbance in The Force, or a glitch in The Matrix. Something had changed among the students entering college (which led me to write The Coddling of the American Mind), and something had changed in American society and politics, which led me to write a series of articles in The Atlantic with titles such as

During this period, I became interested in the great media theorists of the 20th century, such as Neil Postman and Marshall McLuhan. These scholars were writing about the revolution in instant electric communication that began with the telegraph and continued on through the telephone, radio, and television. They told us to avoid getting too caught up in the analysis of the content people were viewing and to think more about the ways that the medium itself (the technology we create) changes who we are and how we think and act.

They offered thrilling analyses of mid-20th century life and mind-bending visions of where technology might take humanity. Here, for example, is quote from the opening of McLuhan’s 1964 book Understanding media: The extensions of man:

During the mechanical ages we had extended our bodies in space. Today, after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned. Rapidly, we approach the final phase of the extensions of man - the technological simulation of consciousness, when the creative process of knowing will be collectively and corporately extended to the whole of human society, much as we have already extended our senses and our nerves by the various media.

If we are not already in that “final phase,” we’re sure getting close.

What on earth is happening to us? To answer that question, Zach and I thought that we need scholars writing for After Babel who can apply the ideas of these men to our time. A month ago, we put out a call for academic collaborators who would be interested in working with us in a variety of capacities, and Nicholas Smyth was quick to reach out. Nick is an Associate Professor in the philosophy department at Fordham University who has been teaching data ethics and the philosophy of the internet for the last four years. Nick has his students read The Anxious Generation, in addition to the works of Marshall McLuhan and Neil Postman.

We invited him to write an essay for After Babel about his experiences teaching this course with students and helping us situate The Anxious Generation within the lineage of McLuhan and Postman... and what he sent is profound. It’s about the changes we need to make to ourselves, intentionally, to preserve our humanity as we are carried along into this next (or final?) phase.

– Jon

Smash The Technopoly!

For the past few years, I’ve been teaching a class called Ethics and the Internet at Fordham University here in New York. As a (rapidly) aging Generation-X philosophy professor, I’ve come to greatly appreciate this opportunity to talk about tech with younger people. I’m learning as much as I am teaching.

One thing I’ve been learning is that opposition to smartphones and to social media is definitely not just a “kids these days” phenomenon, because the kids themselves are often far more jaded and angry about digital technology than I am.

On day one, I always put Jon’s question to my class: if you could erase the smartphone and social media from ever having existed, would you do it? Over the past three years, 81% of them have said ‘yes’.1 These students are of course not representative of the general student population, but even if the real number were something like 50%, something very funny is going on. I ask them: can you think of a new technology, at any point in history, where half of its primary users quickly wished that it had never been invented?

By contrast, I ask my students to consider the humble washing machine. It is hard to overstate the extent to which the primary users of this tech enthusiastically embraced it, despite a few early safety issues. We can be fairly sure that ten years after it spread to most homes, it was not the case that 50% of its users would have wished it had never been invented.

What other tech is like this? The only clear analogue my students usually come up with is the nuclear bomb. Famously, creators and possessors of the bomb often fervently wished they could put that genie back into that bottle. Yet, what does it say about the smartphone and social media that their clearest analogue here is a technology that could easily destroy the entire surface of the earth several times over? Why do so many of my students express a growing sentiment among young people, a nostalgia for what Freya India called “A Time We Never Knew”?

We urgently need to understand the sources of this anxiety and nostalgia. And in my class, we unlock the mystery by beginning with two thinkers: Marshall McLuhan and Neil Postman.

McLuhan and Postman

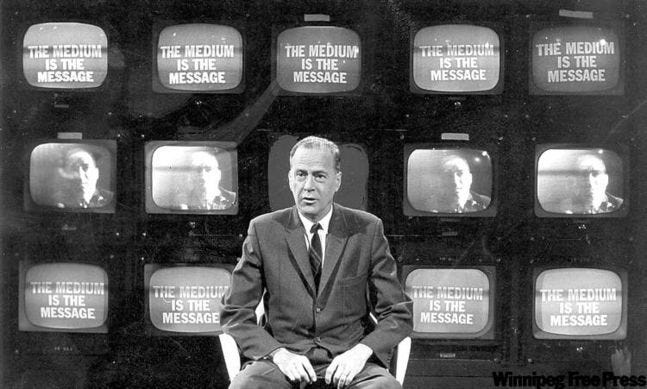

Postman was McLuhan’s student here at Fordham University in 1967. It would be impossible to summarize McLuhan’s sweeping and impenetrable thought here. Instead, let’s just focus on his most-cited idea: the medium is the message.

What does this cryptic, provocative phrase mean? McLuhan notes that our leaders often claim that dominant technologies are good because they are often put to good uses: the TV shows contain educational content, or the guns are often fired at the right targets. McLuhan’s key idea is that the really key effects of any technology arise from its form, from how it is actually constructed. Each technology communicates an implicit message that changes us, gives us new desires, new feelings of possibility. Almost anyone who’s fired a gun can remember the first time they held one; even an anti-gun activist will find themselves seized by a desire to shoot at something. The gun is, in a way, talking to you, delivering messages: you are powerful, you are fearsome, you are magical. It changes you.

My students, upon encountering McLuhan’s idea, immediately see that the smartphone and its typical apps must also be communicating such messages. This year, they offered these examples: your voice matters, people want to see you, you can be popular. It doesn’t matter how many educational podcasts or instructional videos someone consumes, they are holding a device which is delivering these unconscious messages, and those messages are changing them. And readers of this blog know that those changes are not always for the best.

But McLuhan, to the frustration of many readers, never told us how to resist or escape the power of these messages. Postman, his student, rejected this neutrality and argued that we could reclaim control over our machines.

The Technopoly

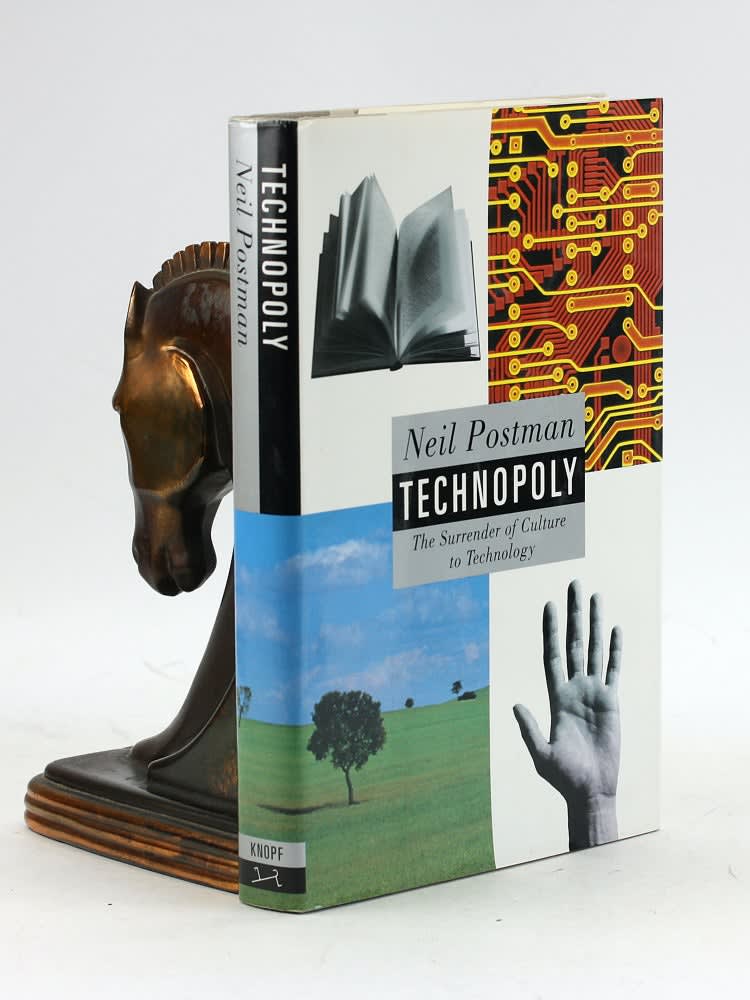

In Technopoly, Postman distinguishes between a tool-using culture and a technopoly. All cultures have tools, but some cultures have moral resources necessary to constrain and direct the uses to which tools are put.

As a clear example, he cites the example of the samurai warriors, whose refinement and use of the katana sword was strictly regulated and directed by powerful social norms. While wielding the sword surely gave someone feelings of strength and possibility, samurai culture restrained those feelings and channeled them towards productive, healthy ends. Thus, the demands of honor required only very specific uses of the sword, and also required the user to commit ritual suicide with the sword if that honor was severely compromised. This is an example of a social group that is in possession of a powerful tool, but which also retains collective control over when and how the tool is used. It is a tool-using culture.

But within a technopoly, the tool becomes the master. It takes on a life of its own, steamrolling over a great many prior moral convictions or constraints.

In 1991, viewers of the series Star Trek, The Next Generation watched in alarm as the crew of the Enterprise were rendered dull, lifeless, brainwashed addicts under the control of “The Game”, an augmented-reality visual pastime. Twenty-five years later, one-third of the people on public transit were staring in a dull, lifeless manner at a pointless, addictive game, and only rarely was anyone alarmed by this.

It didn’t matter that we all started out thinking that this would be super weird and creepy. We got over it, and we got over it quick. That is because we live in a technopoly. Unlike those who lived out the samurai code, we lack the moral resources to pump the brakes when our moral convictions are telling us that something problematic is going on.

The result is exactly what Haidt says it is. Though the vast majority of people throughout human history would have found this utterly strange, bizarre and even terrifying, we collectively decided to let our children and young teens stare slack-jawed at smartphones and social media apps for hours a day. The potentially deep moral wisdom contained in our gut intuitions was steamrolled with ruthless efficiency. The smartphone spread twice as fast as the washing machine, and no-one with any political power seemed capable of even entertaining the idea that we should stop this.

Technopolies and Language

Postman is clear that a technopoly is also powerless to protect its own language from being aggressively commandeered by new technology. This might seem puzzling: how does technology change language?

“New things require new words,” he says, “but new things also modify old words.” So, sometimes, we just get new words: “selfie”, “hashtag” and “deepfake” describe new internet phenomena using fresh terms. But just as often, older words are enlisted in the battle for our minds.

Consider the term cloud as used to describe storage. Cloud storage is a friendly-sounding phrase which encourages us to feel as though our data is stored in some kind of disembodied, abstract network floating above our heads. This of course obscures the reality that thousands of massive, water-hungry, energy-intensive data centers house all of our data.

These linguistic changes are essential to a technopoly, since they condition us away from our prior moral reactions and prepare us for a new reality that might otherwise seem dangerous or at least questionable. And so now, while declaring that teen smartphone use constitutes a national health emergency, the US Surgeon General qualifies his claims by saying:

Social media can provide benefits for some youth by providing positive community and connection with others who share identities, abilities, and interests. It can provide access to important information and create a space for self-expression. The ability to form and maintain friendships online and develop social connections are among the positive effects of social media use for youth. (From Haidt 2024, emphasis mine)

Yet, why are we assuming that words like “friendship” and “community” actually apply to life on social media? It is only by making this assumption that we can conclude that social media actually has these positive benefits. But just as a data center is not a cloud, it is arguable that social media ‘communities’ aren’t communities.

Just fifty years ago, almost no-one would have described a set of disembodied avatars exchanging hot takes and politically charged memes as a “community”. We, on the other hand, let phrases like online community slip off our tongues without a moment’s thought. In doing so, we collaborate in the erosion of our own language, and thus submit to the destruction of our own moral barriers.2

And so, with Postman, I ask: Who is the master? The answer is increasingly clear: it ‘aint us.

This is why smartphones and social media sit in the same category with nuclear weapons. Unlike washing machines, each is a technology that reminds us who the master really is. This is why they produce such extreme anxiety and nostalgia. We don’t like to dwell on this, but deep down each of us knows that in our world, we are not in collective control. We do not have consensus norms and traditions that can constrain the use and development of technology. This is a terrible thought. But is it inevitable?

Why The Anxious Generation Matters

Let’s suppose that we discover that almost every scientific claim in The Anxious Generation is false. In other words, let’s assume that smartphones and social media cause no harms whatsoever. Would this mean that the book is a failure?

Despite what a chorus of plucky critics seem to think, the answer is actually: no. This is because the book actually has a hidden, more fundamental and more radical message: we should smash the technopoly.

This doesn’t mean that we actually smash anything, burn down buildings or dust off the ol’ guillotine. It means that we re-acquire the moral resources to constrain and direct our technology. It means that we start to speak and act collectively in ways that create and reinforce real, effective norms, which can then act as a bulwark against the McLuhan-style messages which may be poisoning us all. It doesn’t mean that we reject any and all new tools, even the smartphone itself. It means that we try to become tool-users.

After all, even if no child or teen had been harmed by smartphones, we didn’t even pause to ask the question. Instead, as Haidt says, we engaged in “the largest uncontrolled experiment humanity has ever performed on its own children.”

That is the sort of thing that a technopoly does. Do we have the collective courage to destroy it? Well, after having taught yet another group of curious, critical and extremely thoughtful students in Ethics and the Internet, I’m here to report that the battle has not been lost. As one just wrote to me:

I think there is hope! Already, my peers and I being equipped with this knowledge has affected our tech usage, and the hope is that it will also influence the advice we give to friends as well as how we will guide the generation after us.

So while the kids may not be exactly “alright”, many of them are at least ready to reclaim control over their lives.

This is above Jon and Zach’s findings that just about 50% of Gen Z’ers report wishing that TikTok and X were never invented (Snapchat and Instagram were not far behind at 43% and 36% respectively).

For more on the loss of community see this post from Seth Kaplan on After Babel, and this post by Zach.

Great article! I hope that the attention and enthusiasm from The Anxious Generation will lead to an overhaul of the just as harmful edtech being used in schools, I think it is about time to smash those 1:1 devices! As an educator in a middle school, I often talk to students about tech use and edtech. About 95% of my students wished they had more paper and books in school rather than a 1:1 device. To quote one 7th grader “It is just easier for me to learn on paper”.

“The potentially deep moral wisdom contained in our gut intuitions was steamrolled with ruthless efficiency.” This is happening now with the bombardment of AI in education too. The amount of emails I receive pushing AI in school is relentless yet it is packaged as the next best thing. Most educators know that it is not but feel powerless. Districts rely on data from these edtech programs to measure how students learn. My question is, since these programs seem to make learning more difficult and seem to create a barrier to learning, then what is the purpose of the data it gives us? Thanks again for bringing attention to such an important topic!

What drives me mad about the "plucky critics" is what they're willing to sacrifice at the altar of "wait for the undisputed science." They seem to be fine with a few kids dead by suicide because of the sextortion schemes that happened through Instagram. They seem to be fine with 3,390 grooming cases through Snapchat, as reported by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. They seem to be fine with another third grader finding porn on their school-issued Chromebook. And even if none of those horrible things happen, they seem to be fine with a slightly diminished version of children who are drawn into these digital spaces.

It's been stated before here on After Babel, but we have it backward. Instead of waiting for "beyond a reasonable doubt" evidence social media and technology are harming our children, we should be waiting for "beyond a reasonable doubt" evidence it's helpful.

Sunset and reimagine CDA 230. Create a design code. Mandate K-12 digital discernment curriculum. Create oppressive personal liability for tech executives who violate said design code. Treat technology like an "attractive nuisance." Technology might be a "wicked problem," but I think we can solve this one. We must solve it.