The new CDC report shows that Covid added little to teen mental health trends

Plus responses to critics from my prior post

For the first few months of this new substack, I plan to publish a major post every two or three weeks. In the weeks in between, like today, I’ll sometimes write something shorter and respond to the best criticisms of my previous post. I’ll usually write these responses with Zach Rausch, the lead researcher for this substack.

Before I get to that, I'd like to address a major story from this week: The publication by the CDC of some of the results from its Youth Risk Behavior Study (YRBS), one of the long-running nationally representative studies that Jean Twenge and I rely upon in our research on Gen Z. On Monday, the CDC put out this 89-page summary of trends from 2011 through the 2021 data collection, which took place in the Fall of 2021 and is just being released now. The survey is administered every other year, so the changes observed between 2019 and 2021 are perhaps the clearest evidence we have as to how covid affected American teens. I’m going to leave aside the questions on drug and alcohol use (mostly down, some by a lot, see p. 28) and violence (mostly unchanged, see p.431). I’m going to focus only on the 6 mental illness items that were released in this report, five of which have increased since 2019, as you can see in Figure 1:

Figure 1. From p. 48 of the CDC’s YRBS report for 2011-2021.

I am glad to see that the report has gotten wide coverage in American media but I want to note a flaw I see in much of it: Many of the articles attribute a lot of the problems teens are having to covid and covid restrictions. That makes sense. We should certainly expect lockdowns, school closures, and constant fear messaging (including the loathsome farewell phrase “be safe”) to take a toll on teen mental health.

But look closely at Figure 1 and you see that there’s not much evidence of a covid effect. What I see in figure 1 is just a continuation of the teen mental health epidemic that began around 2012, as I documented in my previous post.

Here’s the CDC’s graph of responses to the first item, about persistent sadness:

Figure 2, from p. 61 of the CDC report: Percent of males and females who report persistent sadness or hopelessness.

If we start with girls, we see a steady rise since 2011, with an acceleration in the 2019 administration, and then, if you squint, you can see a slight acceleration beyond that in the 2021 administration. We can call that extra acceleration the covid effect. For the boys, we see no covid effect at all. The big jump was between 2017 and 2019, and the rise slows down between 2019 and 2021.

We see the same pattern in the CDC’s graph of responses to the question about serious consideration of suicide: no sign of a covid effect for boys, and a small one for girls:

Figure 3, from p.64 of the CDC report. Percent of males and females who report that they seriously considered attempting suicide.

I’d like to ask 2 questions about these patterns and offer tentative answers, based on what I’m learning as I write Kids in Space.

Question 1: Why did covid not cause a bigger increase in teen mental illness?

My tentative answer: When school closures and social distancing were implemented in 2020, teens had already lost most of their social lives to their phones. You can see the spectacular loss of time with friends in this graph of time use data plotted by age group:

Figure 4. Daily average time spent with friends. Graphed by Zach Rausch from data in Kannan & Veazie (2023), analyzing the American Time Use Study.2

Here you can see a clear covid effect from 2019 to 2020, for all of the age groups who are 25 and older. You can see how the lines bend downward between 2019 and 2020. But look closely at the line for the youngest group, ages 15-24, in blue. This age group used to spend 2 hours a day hanging out with friends because these are teens and young adults. Most are students, few are married. So 2 hours a day with friends was the norm right up to the time when teens traded in their flip phones for smartphones, in the early 2010s. Once they did that, they moved their social lives onto a few large social media platforms, especially Instagram, Snapchat, and later Tiktok. They were spending vastly more time online, even when they were in the same room as their friends, which meant that they had far less time for each other (in face-to-face interaction or physical play).

I suggest that this is why the effect of covid restrictions on teen mental health was not very large: Gen Z’s in-person social lives were decimated by technology in the 2010s. They were already socially distanced when Covid arrived.

Question 2: Why did covid restrictions harm girls more than boys?

My tentative answer: Because Covid restrictions sent girls ever deeper into the arms of social media, which is the largest single cause of the teen mental health epidemic that began around 2012. Time spent on screens went way up for both sexes during the Covid pandemic. But boys don’t use social media as much; they spend far more time than girls playing video games and watching videos on Youtube. Boys are not doing well either, as Richard Reeves has shown, and as I’ll explore in a future post, but their problems are different from those of girls. Boys are failing to develop into socially competent and ambitious men, although they do also suffer from increases in anxiety, depression, and suicide, as I showed in my previous post, and as you can see throughout the Adolescent Mood Disorders Collaborative Review. So in the YRBS dataset, which only has items related to depression and suicidal ideation, we see larger increases for girls.

In my next post, I’ll show the evidence that social media is a major cause, not just a correlate, of the teen mental illness epidemic that began around 2012. There are now many kinds of studies including two categories of experiments that show causality. (There are true experiments using random assignment, and there are natural experiments that exploit the staggered rollout of Facebook or high-speed internet).

If you want a preview of that argument, you can find it in this 12-page document I prepared when I gave testimony at a US Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on social media, in May 2022. I think it is vital that people––especially journalists––stop saying that the evidence is “just correlational,” or that the correlations are too small to matter. Those were reasonable thing to write in 2019, but not in 2023. We now have dozens of experiments, plus some very consistent and incriminating patterns in the hundreds of correlational studies. I’ll lay those out next week.

Responses to Commenters

Now for some responses to my previous post: The Teen Mental Illness Epidemic Began Around 2012, where I showed that what's happening now is not just the same old “kids these days” moral panic that you can find throughout history. This section is for people who read the previous post and had questions or asked questions in the comments section. It’s also for data geeks and people who just like to look at graphs about teen mental health. This section was drafted by Zach Rausch and Jon Haidt.

Critique #1: Why do almost all of your graphs begin in the early 2000s?

Why not start earlier? Starting in the early 2000s makes it difficult to know whether the recent increases in depression, self-harm, and suicide are truly unprecedented, or whether they are normal fluctuations.

(Thanks to multiple readers for this critique, including Salamano, Nicholas Broune, Interested Observer, Timothy Lee, Lila Krishna, and others we may have missed.)

Response: This is a great question. We have been focused on the changes since 2010, so we start in the early 2000s, but some of the datasets do let us look back several decades before that. You are right that we should try to understand the last decade in the context of previous ones. So let’s look at the datasets that allow us to go back much earlier.

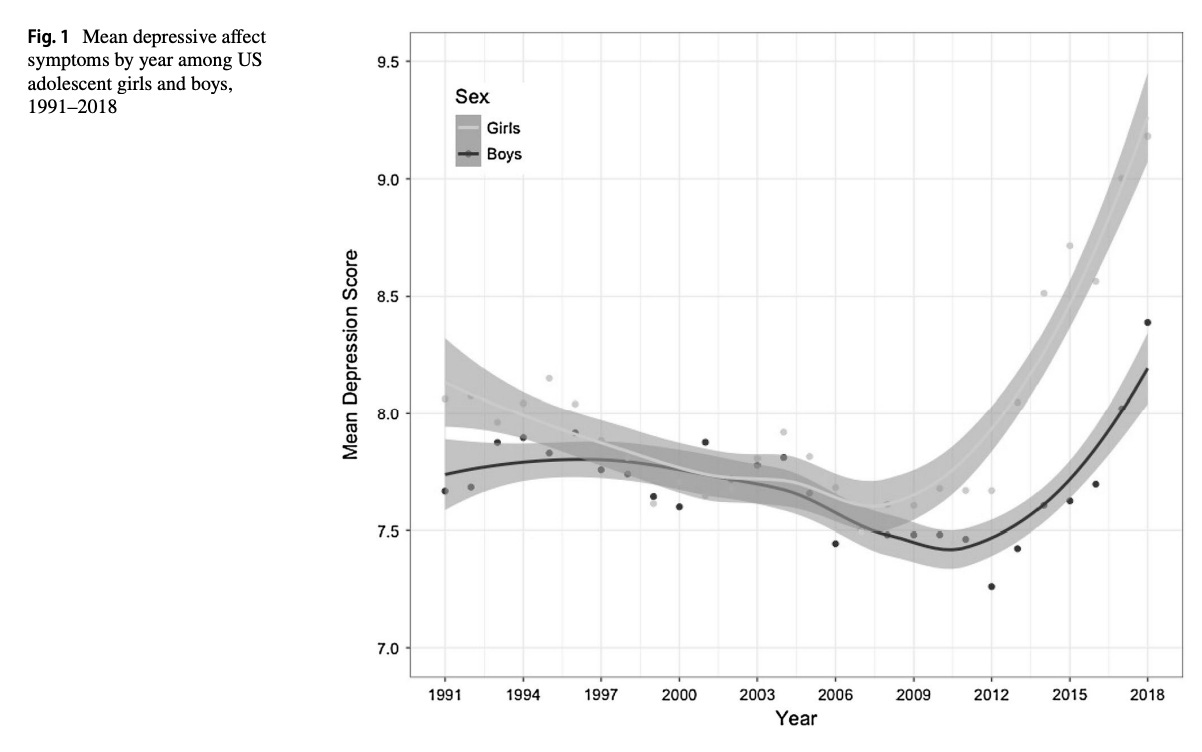

Self-report measures: One of the oldest sources of time-trend data on self-reported mental illness among teens is from Monitoring the Future (MtF). MtF has tracked 12th-grade students since 1975, and they added 8th and 10th graders in 1991. Figure 1 shows trend data in depressive affect symptoms averaged across all three grades from 1991 to 2018. As you can see, the mean depression score for girls declined from 1991-2011 and began a rapid rise beginning exactly in 2013. The story for boys is similar, except that the rise begins later and is not as steep. So when we look at a longer time period, the mental illness epidemic of the 2010s stands out even more sharply as something in need of explanation.

Figure 1. Keyes, K. M., Gary, D., O’Malley, P. M., Hamilton, A., & Schulenberg, J. (2019). Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: Trends from 1991 to 2018. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology.

Behavioral measures: The official source of suicide data for the USA is the WISQARS database administered by the CDC, with data going back to 1981. The CDC publishes separate statistics for ages 10-14 and for ages 15-19. Let’s look at the younger teens first.

Figure 2. CDC Fatal Injury Reports (1981-2020)

Figure 2 shows small fluctuations in the suicide rate for younger teen girls between 1982 through 2011, and a sudden spike in 2013 that continues to rise through 2018. There is no precedent in the older data. For boys, there was a previous period of elevated rates in the 1980s and 1990s, followed by a drop in the 2000s, followed by a much larger rise that seems to begin in 2008. The rapid rise in the 2010s brings the rate to a peak in 2018 that was 1.4 times greater than the earlier peak in 1995. So the 2010s were unlike anything seen previously.

Let’s now look at the older teens (ages 15-19).

Figure 3. CDC Fatal Injury Reports (1981-2020)

The suicide rate among 15-19 year-old girls is consistent with the trends seen in younger teens: It did rise in the 1980s, but it is now higher than it has been at any point since the CDC began collecting data. The trend for the older boys is a little different. Suicide rates substantially increased in the 1980s and early 90s, then dropped steadily until 2012, and then spiked upwards until reaching a new peak (17.35 per 100,000) in 2018, which is in the same ballpark as the highest rate from the previous surge (18.17 per 100,000 in 1990).

Jon had a debate with Chris Ferguson over the meaning of this earlier surge, which you can read in section 3.2 of the Adolescent Mood Disorders Collaborative Review doc. Jon believes that this prior surge is related to a very similar surge in homicide rates, for boys. As you can see on p. 116, homicide and suicide rates used to move in tandem. Jon argues that this is because both surges were caused by the enormous increases in lead exposure for kids born in the 1950s through the 1970s, as leaded gas consumption skyrocketed in the post-war boom. Lead interferes with brain development in utero and early childhood when the frontal cortex is wiring up. When lead was phased out, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the boys born in those years became much less prone to violence when they reached their late teens, which is the prime age for violence and self-destruction. The point here is that the earlier surge in boys’ suicide rates may have been an artifact of lead poisoning. Had there never been leaded gas, it would not have happened. The current surge is caused by something other than lead.

In sum: The current trends in depression and suicide among teen girls are truly unprecedented. Trends among boys are more complicated, but it’s clear that something bad, something new, has been happening to them since the early 2010s as well.

Critique #2: “…The increase in teen suicide and non-fatal self-harm is simply part of the larger trend of increasing deaths of despair across age groups.”

“Old people are killing themselves too, quickly with conventional suicide or slowly through drinking and drugging themselves to death. The teen suicide epidemic is a broader suicide epidemic if you zoom out of that narrow age group.”

(Thanks to Dave Rogers for this critique.)

Response: This is a very important critique––we’ll call it the “general despair” hypothesis. It requires us, again, to look at both self-report and behavioral data across age groups.

Self-report measures: Contrary to the “general despair” hypothesis, one of the clearest signs of a generational mental illness gap is anxiety prevalence. Gen Z and younger millennials have significantly higher rates of anxiety disorders relative to other age groups, and that gap has only been expanding since 2012. Since 2010, there has been a 7% decrease in anxiety prevalence for those above the age of 50 and a 92% increase for young adults between 18-25.

Figure 4. Percent US Anxiety Prevalence. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

Behavioral measures: Differences in anxiety rates may be a function of an increased willingness to discuss mental health challenges. It may be true that the generational gap is not a reflection of the true rates of mental illness, it’s just that Gen Z is much more willing to talk about mental health problems, so we need to look at the behavioral data.

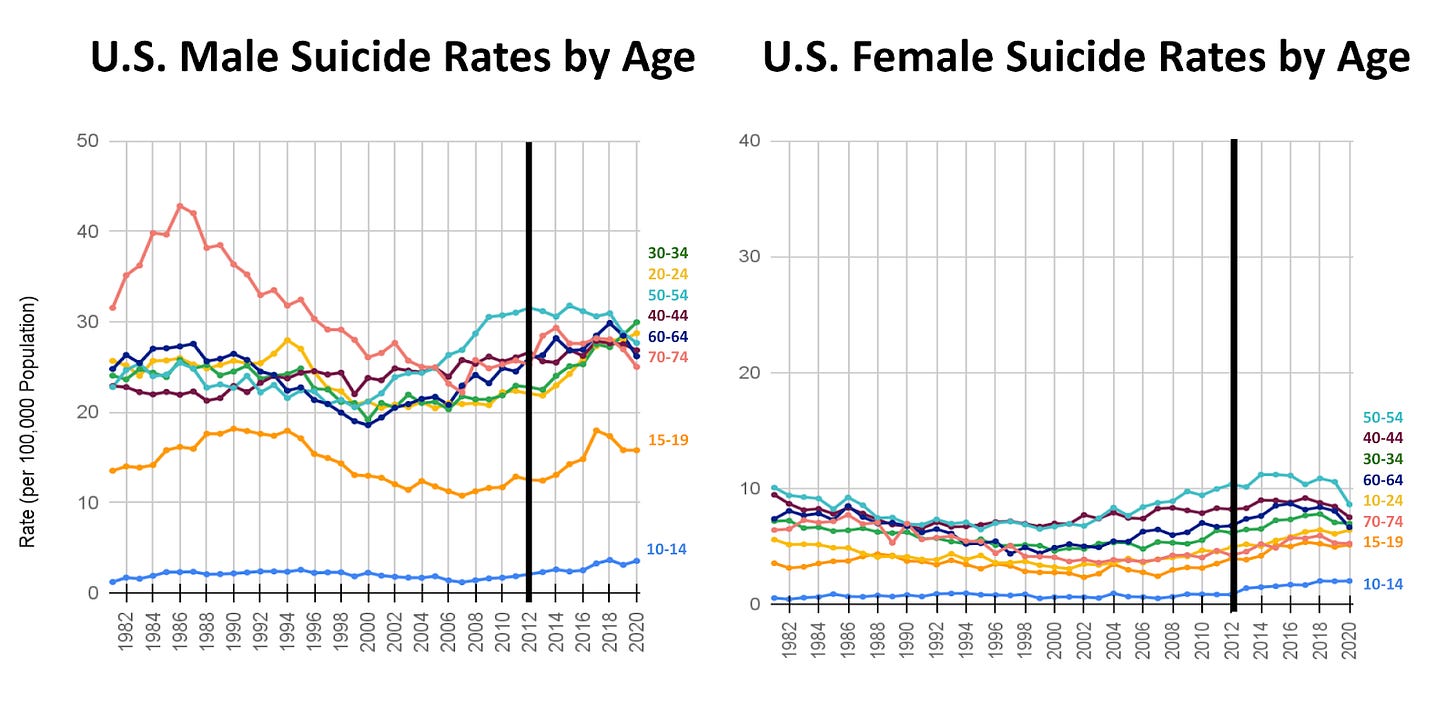

Suicide rates among boys and men: The “general despair hypothesis” has stronger legs here. Suicide rates are much higher among older men than among teenage boys (See Figure 5, left graph) and rates have been generally rising across all age groups since the early 2000s.

Figure 5. WISQARS Fatal Injury Report, CDC (1981-2020). Suicide rates by age per 100,000.

However, it is also useful to look at the relative increase in suicide. As you can see on the left graph in Figure 6, the relative increase in suicide since 2010 is highest among the youngest boys, ages 10-14, with a 111% increase.3

Figure 6. WISQARS Fatal Injury Report (1981-2020), CDC. U.S. Percent change in suicide rates by age (00’-09 vs. 2020).

Suicide rates among girls and women: Suicide rates are also higher for older women relative to younger girls (Figure 5, right graph). Since the early 2000s, there has been an increase in suicides among all age groups. That trend has continued to increase for teens and young adults but has begun to decline for women over 30. And like boys, the relative increase in suicide since 2010 for the youngest girls is far higher than any other age group (with an astonishing 201% increase).

Self-harm among girls and women: The self-harm trends for girls and women are just as striking. Before 2009, the rate of self-harm for 10-14 year-old girls was lower than almost all other age groups (besides those above the age of 50, see Figure 7, right graph). But by 2015, 10-14 year old girls surpassed the rates of every age group except for their slightly older teen counterparts. By 2019, 10-14 year old girls exceeded the 2009 self-harm rates of 15-19 year-old girls.

Figure 7. WISQARS Nonfatal Injury Report, CDC (2001-2020). Nonfatal self-harm rates by age per 100,000.

Figure 8. WISQARS Nonfatal Injury Report, CDC (2001-2020). Percent change in nonfatal self-harm (01’-09) vs 2010.

Self-harm among boys and men: The self-harm trends for boys and men show quite different patterns (Figure 7, left graph). Compared with women, rates of self-harm across all age groups are significantly smaller. Nonetheless, we do see a comparably small, but significant increase in self-harm post-2010 for the youngest males, and the oldest age group plotted (60-64).

Critique #3: Isn’t everything rising?

“The argument about more diagnosis and less stigma is also a good one, especially because there appear to be increases in all sorts of conditions, not just the anxiety and depression one might expect from social media usage but also ADHD (neurological) and schizophrenia. Why, with so much mental health treatment (not just through regular health care but the gobs of social workers in schools today), do the numbers not go down? Perhaps constantly talking about mental health doesn’t actually improve mental health?”

(Thanks to Holly L. for this question. And Martin Tournoij for a similar comment.)

Response: This is another excellent critique. We acknowledge that there have been changes over the last decade or so in normalizing and destigmatizing particular mental illnesses, particularly depression and anxiety (thus leading to increases in the willingness to discuss these issues). We also do not disregard the hypothesis that the mental illness diagnostic bar has been lowered.4 Jon directly addressed these concerns in chapter 7 of The Coddling of The American Mind:

Have things really changed so much for teenagers just in the last seven years? Maybe Figure 7.1 merely reflects changes in diagnostic criteria? Perhaps the bar has been lowered for giving out diagnoses of depression, and maybe that’s a good thing, if more people now get help? Perhaps, but lowering the bar for diagnosis and encouraging more people to use the language of therapy and mental illness are likely to have some negative effects, too. Applying labels to people can create what is called a looping effect: it can change the behavior of the person being labeled and become a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is part of why labeling is such a powerful cognitive distortion. If depression becomes part of your identity, then over time you’ll develop corresponding schemas about yourself and your prospects (I’m no good and my future is hopeless). These schemas will make it harder for you to marshal the energy and focus to take on challenges that, if you were to master them, would weaken the grip of depression.

In other words, the diagnostic bar has probably been lowered somewhat, but this does not just cause the appearance of an increase without touching the reality. Rather, a lowered bar combined with reduced stigma, combined with social media communities in which mental illness sometimes confers prestige, may be causing a real increase in levels of mental illness and suffering across the board.

Critique #4: Didn’t the epidemic start a few years before 2012?

“I wonder why you say it started ‘around 2012’—all of these graphs make it look like it was closer to 2009, no? (I know it's a little arbitrary to pinpoint an exact year but I still think saying it was around 2009 is a more descriptive of these graphs than saying it was around 2012, and that three-year difference might be important regarding the hypothesis that the cause was phones/social media.)

(Thanks to Ines for this question. Morris Fiorina, from Stanford University, emailed Jon a similar question.)

Response: It depends on how we interpret dips. In the graphs we showed about self-harm, there seems to be a dip for all four lines in 2009, which makes it seem that the rise began in 2010. For suicide, all four lines dip in 2007, which makes it look like the rise began in 2008. Perhaps something happened, something changed, in those first years after the dip. (It can’t be the Global Financial Crisis, as Jean Twenge and I showed; mental illness rises steadily in the 2010s, as economies improve. And we see the same mental illness trends in Canada, which had no financial crisis.) Or perhaps the dip was a fluke, and the next year returns to normal, which seems to be the case for the young girls’ suicide rates, which stayed steady until a sharp jump in 2013. We will keep this critique in mind as we examine other datasets, and especially in our future post on what is happening internationally. To give a little preview of that post, here’s some data on self-harm rates in the UK:

Figure 9. from Cybulski et al. BMC Psychiatry (2021).

At least in this graph, 2012 seems to be a better choice than 2008 or 2010. But as with most social trends, they may start small and start an exponential curve, which doesn’t show up as a sharp upturn for a few years. We are open to saying that the epidemic starts a few years before 2012, and seems to speed up around 2012. We’ll see as we go on.

Oh my, this was supposed to be a short post, in between two larger ones. Thank you to all who commented on the previous post. As always, please leave us comments below, and we’ll respond to some of them in future posts.

Jon and Zach

While none of the measures of violence were up overall, there were some interesting demographic variations. A lot of attention is being paid to the finding that the percentage of girls who say that they were “ever forced to have sex” rose from 11% in 2019 to 14% in 2021, even while the percentage of teens who say that they have “ever had sex” dropped from 38% down to 30%.

Thanks to Andy Rowell for pointing out that the generational labeling on Figure 4 was unclear and misleading. He said, “The chart creator Zach Rausch means in 2021 that Generation Z is 15-24. He should not have inserted the parenthetical labels or should have written (Gen Z in 2021). That is the only use of Generation terminology in the whole article.”

We note that very large relative increases are most common when the starting value is very low. Thankfully, the number of suicides among boys 10-14 is very low, as you can see in figure 5. The absolute increase is from 1.68 per 100k to 3.56 per 100k, which is how we calculated the 111% increase shown in Figure 6.

A sudden spike in psychiatric diagnoses is known as “diagnostic inflation.” A recent meta-analysis challenges the sweeping claim that there have been significant changes in diagnostic inflation. But the same study does show significant inflations/deflations among specific disorders including ADHD, Autism, Anorexia, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder, among others (due to updates and revisions to the DSM). A number of other researchers share the concern about this pattern of overdiagnosis.

It would be interesting to see if the trend is also reflected in homeschoolers. This might be one sub-group of the population that is less likely to use social media/ or use it to a lower extent. There is less peer pressure, closer ties to family, and a smaller group of closely connected friends. I coordinate co-ops for homeschooled high school students and have observed that phones rarely play any role in their interactions. A group of them actually decided to delete all their social media apps on their phones; they have kept it up and encourage each other. They have decided to use their phones only for making arrangements or taking photos. Many of them have clearly decided that they prefer to be grounded in reality rather than lost in space.

42% of high schoolers experiencing persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness is so unbelievably striking and bleak.