The Mental Health Crisis Has Hit Millennials

Why It Happened and Why It’s Bad For Democracy

Today we have a second post from Jean Twenge, to mark the day that her new book comes out: Generations: The Real Differences between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents—and What They Mean for America's Future. I strongly recommend this book. In fact, here’s my endorsement of it, on the back cover:

Gen Z is really different from previous generations, as Jean Twenge showed us in her previous book, iGen. Now, with Generations, Twenge gives us the big picture of all six living generations. This is a gripping family saga in which Twenge shows not just how we all differ from our parents and children, but why. It’s not mostly because of major events; it's a far more interesting story about technology and the slowing down of childhood development. Generations is vital reading for parents, teachers, managers, and anyone else who works with young people and wants them to do well.

I have been so focused on what happened to Gen Z that I have not mastered the findings on other generations. But Jean has, and in the post below she shows us how important it is to track mental health changes in all generations simultaneously. Her book is full of stunning and shocking graphs showing the extent of recent changes to the two youngest generations. Her post below shows a few of those.

— Jon Haidt

After my book iGen was published in 2017, I traveled the country giving talks about how smartphones and social media impacted the lives of Gen Z teens and young adults. But in city after city, I often got the same question: “Hasn’t this new technology affected all generations?”

That got me thinking. The traditional view of generations theorizes that experiencing major events (wars, terrorist attacks, economic recessions) at different ages causes generational differences. But technology – not just smartphones but washing machines, airplanes, modern medicine, and so on – have changed day-to-day life much more than events.

In my new book, Generations, I explore how technology is at the root of generational differences – not just for Gen Z but for all generations. I examine how the six generations with a quorum of living members – Silents, Boomers, Gen X, Millennials, Gen Z, and Polars – differ in everything from sexuality to politics to work attitudes to gender identity to wealth. These differences happen because technology has not only direct impacts but indirect ones, like the growth of individualism and the slowing of the life course (the latter is why, for example, Gen Z teens delay getting their driver’s licenses, Millennial young adults delay having children, and middle-aged Gen X’ers and Boomers look younger than their grandparents did at the same age.) My goal is to help the generations understand each other better by separating the myths from the realities of generations with as much data as possible (39 million people across 24 datasets).

One big focus in Generations is trends in mental health. After documenting the alarming rise in depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicide among Gen Z teens, I was curious whether the increases had spread to Millennial, Gen X, and Boomer adults as well. I wanted to know:

Are adults also more likely to suffer from depression in recent years?

If so, what are the consequences of the rise in depression for democracy and society?

If so, what are the causes of the rise in depression for teens and adults?

Let’s take these questions in turn.

Question 1. Are adults also more likely to suffer from depression in recent years?

In 2016, a study in Pediatrics came to a startling conclusion: Rates of major depression among U.S. adolescents (12- to 17-year-olds) rose significantly between 2011 and 2014.

A few years later, with data up to 2016, my colleagues and I found that depression among young adults (18- to 25-year-olds) had also started to rise, beginning about two years later (2013) than it did for teens.

The analyses of this dataset for Generations, with data up to 2021, showed something new: Depression rates among 26- to 34-year-olds (nearly all Millennials by 2021) were also up, with increases beginning after 2015 (see Figure 1). These increases were not as large as for teens and younger adults, but they were novel – and concerning.

Figure 1. Percent of U.S. adolescents and adults with major depressive episode in the last year, by age group, 2005-2021. Source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health (a yearly nationally representative survey of 70,000 U.S. adolescents and adults directed by the Department of Health and Human Services)

NOTE: For each age group, the asterisks appear at the year immediately before depression begins to steadily increase. 2020 data is not shown as data collection differences make it difficult to compare with other years.

Similar trends appeared in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, where adults were asked how many days in the last month they experienced poor mental health (such as feeling down or stressed). Just as with depression, young adults rose first and furthest, followed by 26- to 34-year-olds. There was less lag between the initial increases – a year (see Fig 2) instead of two years (see Fig 1) and some evidence for increases among those over age 35 (mostly Gen X and Boomers), but the basic pattern was the same.

Figure 2. Number of days per month of poor mental health, U.S. adults, by age group, 1993-2021. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (a yearly survey of 100,000+ U.S. adults administered by the CDC)

NOTE: This survey allows a more precise look at adult age groups than the survey in Fig. 1, but 35+ is used to be consistent with Fig. 1. 35- to 39-year-olds also showed increases in poor mental health days after about 2016, but there was no noticeable increase among those 40 or older after 2016 (see Figure 5.70 in Generations). For each age group, the asterisks appear at the year immediately before poor mental health begins to steadily increase.

The rise in depression and poor mental health was moving up the age scale – it started with teens, stretched to college-age adults, and by 2016, was ensnaring 26- to 34-year-olds who were building careers and families. This last group was also a different generation: All 26- to 34-year-olds in 2014-2020 were Millennials, born 1980-1994 – a generation that was, at least as teens, actually happier and more satisfied with their lives than Gen X’ers (born 1965-1979) were. So this wasn’t just about Gen Z aging into older age groups.

Like a cancer, the mental health crisis that first afflicted Gen Z teens spread to Gen Z young adults and then to Millennials. The problem wasn’t getting better – it was getting worse, and it was pulling in an age group and a generation who, at first, were not affected.

That’s bad news on many levels, especially if our goal as a society is to reduce human suffering. These are screening surveys getting a cross-section of the population, not just those who seek help. These data suggest the need for more mental health services will only grow – not because more people are comfortable seeking help, but because more people need it. The deterioration of mental health among Millennials will have ramifications for the nation, as they will more likely struggle building families and succeeding at work.

Question 2. What are the consequences of the rise in Gen Z and Millennial depression for democracy and society?

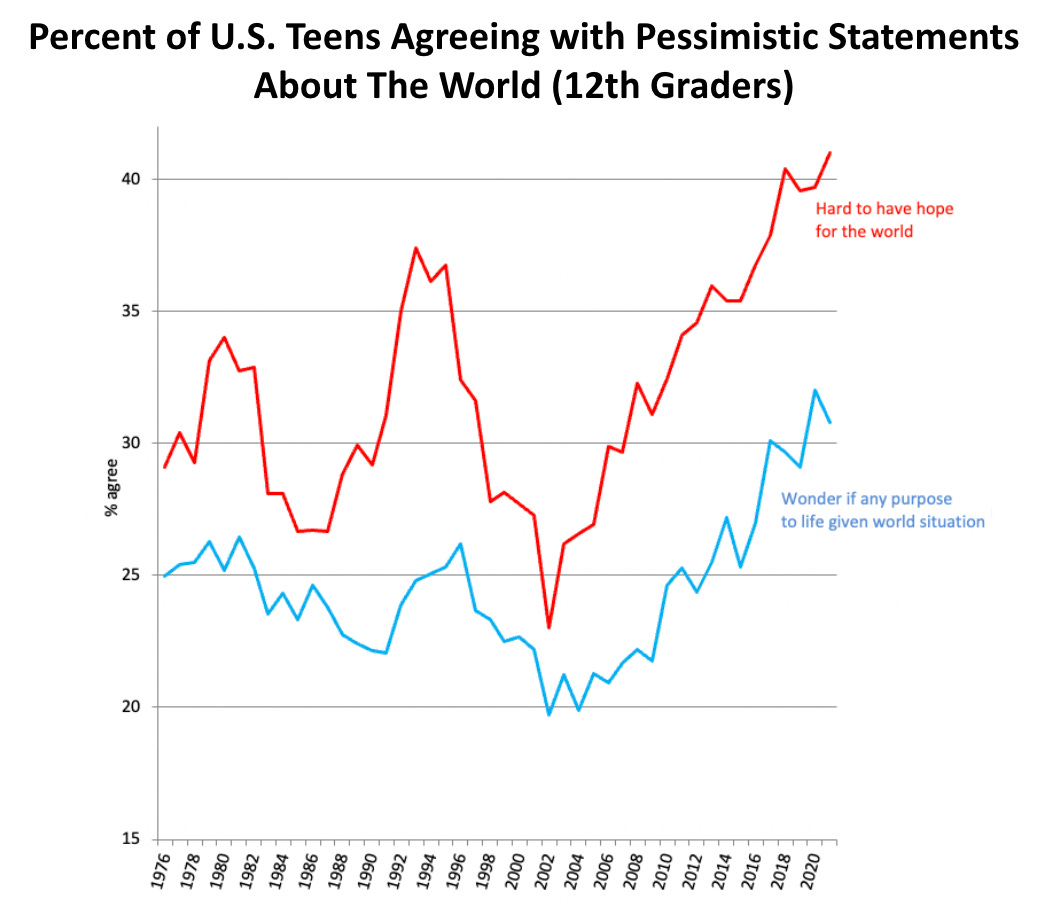

Most people think of depression in terms of emotions: Sadness, despondency, worry. But, as practitioners of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) observe, depression is also about how people think. By definition, people who are depressed have a negative outlook of things. So, given the rise in teen depression, it makes sense that Gen Z teens are much more pessimistic about the world – a trend that started when Millennials were teens in the 2000s (see Fig 3).

Figure 3: Percent of U.S. 12th graders agreeing with pessimistic statements about the world, 1976-2021. Source: Monitoring the Future, Generations Chapter 6.

Are these fluctuations in pessimism reflections of depression trends or or do they hue close to some objective reality of how bad things actually are?

They seem to be more about depression shaping perception, than perception shaping depressive outlooks. For example, although teens’ pessimism sometimes spikes during difficult times (such as the high violent crime rates in the early 1990s), the first survey after the 9/11 attacks saw an all-time low in pessimism among teens. Likewise, instead of declining when the U.S. economy went on a tear from 2012-2019, pessimism went up. (Nor is the change in pessimism a response to climate change: Teens’ concern about the environment peaked in the 1990s, not recently – that’s shown in the Gen X chapter of Generations).

Both Millennials and Gen Z are also more pessimistic about capitalism. While younger adults once had a more positive view of capitalism than older adults, that flipped in the early 2010s. Younger adults in 2018-2021 were considerably less positive about capitalism than in 2010 (see Fig 4).

Figure 4. Percent of U.S. adults with a positive view of capitalism, by age group, 2010-2021. Source: Gallup polls and Della Volpe (2022); Generations, Chapter 6.

NOTE: The item asks “Just off the top of your head, would you say you have a positive or negative image of … capitalism?”

These pessimistic trends are consistent with the “hellscape” narrative, intimately familiar to most digital media users in recent years. It’s the meme of the dog sitting inside the burning house with the “this is fine” speech bubble. It’s the ubiquitous Millennial complaint about stagnant wages (which, it turns out, isn’t true, as the Generations excerpt in the Atlantic shows). It’s the claim that racism and injustice are worse now than ever (which isn’t true either, given that racial segregation was the law in the American South in the early 20th century). It’s the idea that the world is literally on fire, so there’s no point. It’s Washington Post reporter Taylor Lorenz tweeting in February 2023, “We’re living in a late stage capitalist hellscape during an ongoing deadly pandemic [with] record wealth inequality, 0 social safety net/job security, as climate change cooks the world … [you] have to be delusional to look at life in our country [right now] and have any amt of hope or optimism.”

Image: KC Green, “On Fire”

Negativity is more common on the political left, but a variation appears on the right as well. It’s the “this country is going to hell in a hand-basket because of the liberals” narrative of degeneration. It’s the fear that drag queens are coming for your kids. It’s saying that crime has risen so much in the liberal-controlled big cities that they are unlivable. It’s the idea that there’s a war on Christmas. It’s Make America Great Again (because its best days were in the past). These views are likely more common among older people, partially because more conservatives are older, but it suggests that not all of the negativity is coming from the left. The national conversation is much more negative, polarized, and toxic than it once was.

No matter its political origin, pervasive negativity, especially if it is paired with a sense of hopelessness, is problematic for maintaining a stable society. For a democracy to thrive, it helps if its citizens believe that (1) the system is reasonably fair, (2) the government functions reasonably well, and (3) that the country was founded by good people with good intentions.

Among Gen Z and Millennials, all three of those beliefs are in question. Young adults are less likely to agree that “America is a fair society where everyone can get ahead” – the majority disagreed. Plus, 3 out of 4 Gen Z’ers, and 2 out of 3 Millennials, think “significant changes” to the government’s “fundamental design and structure” are necessary.

Most stunning is this: 4 out of 10 Gen Z’ers believe that the founders of the United States are “better described as villains” than “as heroes.” Fewer than 1 out of 10 Boomers agreed, creating a substantial generation gap (see Fig 5). So young adults are not just more negative about the current situation; they are also more negative about events 250 years in the past.

Figure 5. Percent of U.S. adults who agree with negative statements about the country, by generation, 2020. Source: Voter Survey, Democracy Fund; based on Generations Chapter 6.

If young people are this negative about the country, what is going to happen next?

Negativity isn’t always bad – we don’t want people to be overly optimistic and deny the problems the country has. But if that negativity is paired with hopelessness, or a desire to tear everything down and start over, prosperous stability and progress is unlikely to be the result.

Increases in depression are probably not the sole cause for these generational differences in negative appraisals of the country; rising political polarization and reinforced online negativity likely contributes as well.

Regardless, if depression and unhappiness are contributing to increases in nihilism or political radicalism, we have yet another reason to solve the mental health crisis.

To do that, we have to figure out what caused it.

3. What is causing the rise in depression among Millennials and Gen Z?

Theory A: The Smartphone and Social Media Theory (SSM)

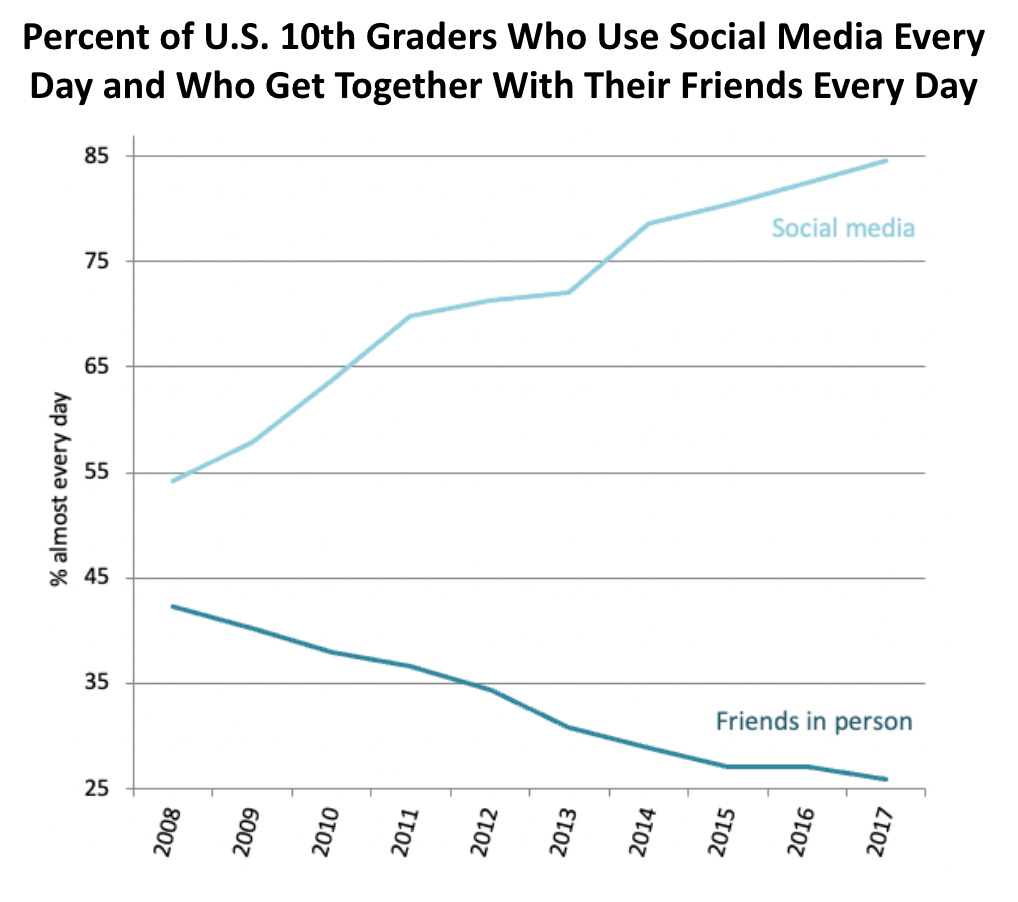

As I have argued elsewhere, including in my 2017 book iGen, the rise of smartphones and social media are the most plausible explanation for the rise in teen depression beginning around 2012. The way teens socialized with their friends shifted toward digital media and away from in-person get-togethers. Jon Haidt refers to this as part of the “Great Rewiring” of childhood that happened in the early 2010s. These changes had a profound impact on how teens spent their time outside of school (see Fig 6).

Figure 6. Percent of U.S. 10th graders who use social media every day and who get together with their friends every day, 2008-2017. Source: Monitoring the Future.

NOTE: Questions about social media use were only asked 2008 and later. Question wording for both items changed in 2018, so only data up to 2017 is shown.

There is very close alignment between these changes in socializing and the increase in teen depression (see Fig 7). As teens started spending more time on social media and less time with friends in person, depression rose. It is difficult to think of any factor, other than this shift in technology use and socializing, that impacted teens’ day-to-day lives so significantly from 2008 to 2017.

Figure 7. Depression, social media use, and seeing friends in person, U.S. teens, 2008-2017. Sources: National Survey of Drug Use and Health, Monitoring the Future

NOTES: Depression rates are among 12- to 17-year-olds. Social media use and seeing friends in person are among 10th graders. Numbers are standardized using Z-scores and, for seeing friends, reversed so the trends move in the same direction. Questions about social media use were only asked 2008 and later. Question wording for both social media and seeing friends changed in 2018, so only data up to 2017 is shown.

Social media use and the decline in time with friends even partially explains the much-discussed result that the rise in depression has been larger among liberal teens compared with conservative teens.

Liberal teens spend more time on social media: In Monitoring the Future data 2018-2021, 31% of liberal girls spent 5 or more hours a day on social media, compared to 22% of conservative girls. Liberal teens also spend less time with friends in person than conservative teens – and this was not the case before 2010 (see Fig 8 for girls). Liberal teens’ socializing changed more in the age of the smartphone, and that was not good for mental health.

Figure 8. Percent of U.S. 12th grade girls who go out with friends two or more times a week, by political ideology, 1976-2021. Source: Monitoring the Future; Generations, Chapter 6.

Jon and Zach have argued that the increased focus on identity, fragility, and trauma in liberal spaces may have driven teen liberals’ depression up after 2012. But perhaps the causation is reversed: Spending more time on social media and less time with friends in person led to depression, which then led some young people to focus more on group identity and trauma and to increasingly see the world as a battle between “us vs. them” (which Jon and his co-author Greg Lukianoff refer to as one of the “Great Untruths.”)

One thing I can’t figure out: If more focus on identity and victimhood in liberal spaces is the cause of increasing depression among liberals, why did liberal teens’ loneliness also increase first and fastest? (see Fig 9).

Figure 9. Percent of U.S. 12th graders high in loneliness, by gender and political ideology, 1977-2021. Source: Monitoring the Future and Generations Chapter 6

NOTES: Graph shows percent with a score of 3 or above on the average of six items measuring loneliness on a 1-5 scale.

Wouldn’t focusing on identity create a feeling of belonging with others who feel the same, and thus lead to less loneliness, or at least stability in loneliness? But if the rise in teen depression is mostly about the changes in time spent online vs. in person, it would make sense that loneliness would rise first and fastest among liberals, since socializing changed first and fastest among liberal teens. Socializing in person is much more likely to relieve loneliness than social media, where many teens see what their friends and schoolmates are doing without them.

Declines in face-to-face socializing may also help explain the increases in depression among adults. The largest declines are among the young (15-25), but there are also noticeable declines among those ages 26 and up (see Fig 10).

Figure 10. Minutes per day spent socializing in person, U.S., by age group, 2003-2021. Source: American Time Use Survey, administered by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and Generations Chapters 5 and 6.

NOTE: 2020 data is not shown as data collection differences make it difficult to compare with other years. The sharp drops in 2021 reflect COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

The decline in socializing mirrors the pattern in depression rates: Larger changes among 15- to 25-year-olds that occur a few years earlier than those for ages 26 and up. In fact, time with friends among 15- to 25-year-olds had declined 17 minutes a day by 2018-19, before the pandemic. For 26- to 34-year-olds, the decline starts after 2014-15 and is smaller: 5 minutes a day by 2018-19. For those 35 and older, it’s 3 minutes less a day between 2014-15 and 2018-19. That means teens and young adults (aged 15-25) spent about two hours less per week socializing, while 26- to 34-year-olds spent about a half hour a week less, and those above 35 spent about 20 minutes a week less.

As with teens, there’s very good alignment between the increase in depression and the decrease in socializing for 26- to 34-year-olds (see Fig 11).

Figure 11. Depression and in-person socializing, U.S. 26- to 34-year-olds. Sources: National Survey of Drug Use and Health, American Time Use Survey

NOTES: Numbers are standardized using Z-scores and, for socializing, reversed so the trends can be plotted in the same direction.

Still, the declines in social time among 26- to 34-year-olds (Millennials) are only ¼ the size of those for 15- to 25-year-olds (Gen Z). Thus, it’s worth asking if other factors might account for some of the increase in depression among Millennials, especially since the timing is so different than among Gen Z. What else happened around 2015 that might explain why depression started to rise among Millennials?

Theory B: Something else

This is where I need your help: I don’t know.

The increase in depression among Millennials wasn’t due to Trump – it started before he was president, and it occurs in both blue and red states (see the Millennial chapter in Generations). It wasn’t the economy – the U.S. economy was on a tear between 2015 and 2019. It wasn’t Millennials’ unique economic situation. From 2011 to 2019, the median income of Millennials soared even when corrected for inflation. By their early 30s, Millennial wealth had caught up to previous generations. Even Millennial home ownership is very similar to Gen X’ers or Boomers at the same age.

Increases in depression might be due to increased political polarization, but polarization had been rising for a decade or two before 2015 (see the Millennial chapter in Generations). Perhaps there was a tipping point where partisan relationships became so nasty that it was literally depressing. But why would that mostly impact younger adults?

It could be the toxicity on social media and in the news – negative clicks get “engagement” and thus profit. Also, personalized social media algorithms started to get more sophisticated around 2015. If the new digital information ecosystem created a consensus that everything is a dumpster fire, depression might follow. This could explain the generation gap, as younger adults spend more time on social media than older adults.

One other significant change occurred around 2015: what journalist Matt Yglesias called“The Great Awokening.” Very suddenly, in 2015, the number of U.S. adults who said “the country needs to keep making changes to make Blacks equal to Whites” went up, and the number who said the country had “already made those changes” went down (in Pew Research Center polls). Not only that, but Americans became much more dissatisfied with the state of race relations in the country (see Fig 12).

Figure 12. Percent of U.S. adults dissatisfied vs. satisfied with the state of race relations in the country, 2001-2022. Source: Gallup polls; Generations, Chapter 5.

Lots of other graphs in Generations look like this too, with attitudes around race fairly stable until 2015 and then suddenly changing (primarily among liberals and Democrats).

But why would a focus on social justice lead to more depression? Wouldn’t coming together with like-minded people for a cause lead to less depression? Those are questions I can’t answer.

So I will put it to you: Why do you think 26- to 34-year-old Americans became more depressed after 2015?

I'm a millennial who was very involved in identity / social justice issues from around 2012 to 2019 — both online and off, but I believe I got into it early due to being very online. My mental health during this period sank like a rock, but it's rebounded tremendously since leaving that world (especially the online parts of it) in 2020.

So when you ask: "Wouldn’t focusing on identity create a feeling of belonging with others who feel the same, and thus lead to *less* loneliness, or at least stability in loneliness? [...] But why would a focus on social justice lead to more depression? Wouldn’t coming together with like-minded people for a cause lead to *less* depression?"

My answer is a STRONG no. Not under present circumstances. Especially not online.

A focus on identity, especially internal identities such as sexual orientation and gender identity, is in large part a focus on the *self.* There is a place for focus on the self — but too much becomes a problem, and fast.

People who join online networks centered around such identities are not coming together to form communities in a meaningful sense. They are rarely making friends or even significant acquaintances who will be there for them in the real world. Instead they are converging online to engage in *co-rumination*. That is, they are fixating on the self, together.

The worst of these networks actively strengthen the feeling of disconnection from others even within the group as members are encouraged to divide themselves among ever more specific micro-identities, which are often conceived as hostile toward one another, even if unintentionally ("microaggressions" abound). Or you might think of yourself as the specific combination of *all* your various identities — racial, sexual, etc. — believing people who differ in any way just can't understand you. This can actually *decrease* interest in finding offline community related to the identities. For example, in circles I ran in, it was common for people to be afraid to go to pride events, having convinced themselves that other members of the alphabet soup hated their micro-subgroup in particular and would somehow turn them away.

By the same token, immersion in such networks can hurt members' existing, offline relationships. The focus on being oppressed increases negativity and decreases trust. There's a common message that members of "oppressor" identity groups (straight people, cis people) are all biased against you, even if they seem accepting. That actually, even if you felt perfectly safe before, you're in danger all the time. I've watched people strain their relationships with their family and friends, not because those people actually did anything wrong, but because of this categorical identity-based mistrust.

And that's not even going into the climate of fear that you'll step slightly out of line and the people you consider your friends will denounce you in the harshest terms, or the pressure to get out ahead of this and prove your loyalty to the group/cause by proactively denouncing others.

The offline identity/SJ-based communities I was part of were better — at first. But slowly, more members got involved in such online networks, and more new people joined who were steeped in them, and the groups became dominated by the maladaptive dynamics described above. One by one the older members — Gen X and up — who didn't like this left or (less commonly) kowtowed, making it worse.

Profound loneliness was the result, and so was a maladaptive way of thinking about that loneliness. The idea that said loneliness was inevitable by dint of your highly individualized identity, the intractable oppression of that identity, and the failure of "communities" based on that identity to provide the real relationships needed to reduce the loneliness.

"Coming together for a cause" *should* confer an anti-depressant sense of meaning and belonging, but it can't if what you're doing is more like wallowing in hopelessness and self-preoccupation than actually working together to help others.

Obviously this is just one person's perspective. I'm sure there are many people whose experience is much milder. I'm also sure there are many other factors going into the complex phenomenon that is this mental health crisis. But I think the broad strokes of this are pretty widespread, and I've watched over the years as the attitudes I've described surfaced among the whole gamut of people I know, from close friends to extended family members to diverse long-term acquaintances, with the commonality being that they identified as some kind of LGBTQ+++ and had gotten involved in online identity/SJ networks.

tl;dr: Identity/SJ-focused online activity can *increase* loneliness and depression through pretty straightforward mechanisms, especially excessive self-focus and mistrust.

One possible explanation for the rise in rates of depression among millennials around 2015 is dating apps. For example, Tinder had 90,000 subscribers at the beginning of 2015, 900,000 at the beginning of 2016, 1.8 million at the beginning of 2017, and 3.4 million at the beginning of 2018 (scroll down to the "Tinder quarterly subscribers" chart here: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tinder-statistics/). Fortunately, I met my spouse without a dating app, but I've heard from my single friends that they can cause a lot of negative emotions. And even after someone meets a partner on the app, I worry that knowing that there are hundreds of other potential matches out there can weaken a relationship. It's harder to commit if you think there's a chance you could slightly optimize over your current partner, and I suspect that this relational instability can also make people more prone to depression.