How To Reduce the Sexual Solicitation of Teens on Instagram

Suggestions from Meta whistleblower Arturo Béjar, which could have been implemented long ago

Introduction from Jon Haidt:

On October 27, 2023, I received a cryptic email from a friend introducing me to Arturo Béjar and suggesting that we should talk. I was in a frantic period of final revisions on The Anxious Generation, so I asked Arturo for more information before I would agree to talk with him on Zoom. He said he could not explain it by email, but it would all make sense in two weeks.

Eleven days later, Arturo gave damning testimony to a Senate Judiciary subcommittee about Meta’s repeated failures to take relatively simple steps to improve the safety of all users, particularly teens. Arturo had been a high-level employee at Facebook and Instagram, leading teams working on safety and security. When he found out that his own 14-year-old daughter had been regularly receiving sexually suggestive comments and propositions on Instagram and had no way to report them, Arturo suggested some relatively simple fixes that would make it easier for future users to report such behavior and that would allow the company to help when this happened. The company took no action. In fact, over time, some of the safety features that Arturo’s team had implemented years earlier were removed. Arturo then shifted his efforts to lead an internal study of the extent to which teens had harmful experiences on Instagram. The results were staggering, and he ensured that the executive team was aware of his findings.

Arturo told his story in that Senate hearing, in the 291 pages of evidence he submitted along with his testimony, and in the set of documents he posted on his own website, intended to help the industry to do better. But perhaps because of the crush of world news around that time, the news coverage was relatively brief. This is a shame because, like Frances Haugen before him, Arturo gathered evidence carefully and laid out possible solutions explicitly. Zach and I believe Arturo’s story needs to be more widely known, so we invited him to revise one of his essays and tell his story here, with links to his other essays at the bottom of this post.

Arturo’s bombshell finding was that 13% of teen users of Instagram between the ages of 13-15 said that they themselves had received unwanted sexual advances…. In the past week! When you multiply that high weekly rate by the vast number of teens and pre-teens using Instagram all around the world, you arrive at this shocking conclusion, which Arturo reports below but I want to emphasize here at the top:

“Instagram hosts the largest-scale sexual harassment of teens to have ever happened.”

The numbers are similar for 13-15-year-olds who have seen “any violent, bloody, or disturbing images on Instagram” (13% in the past week) and for seeing “nudity or sexual images on Instagram that you didn't want to see” (19%).

This must stop. In The Anxious Generation, I called for four new norms, one of which is “no social media before 16.” Arturo’s findings and experience make it ever more clear that effective age gating is essential on the platforms that now govern young people’s lives. Interacting with anonymous strangers on platforms that have so far enjoyed near total immunity from legal liability for the harm they cause every day… is just not appropriate for children, or even for teens.

— Jon

Introductory note from Arturo:

In order to support social media regulatory and transparency efforts, I am publishing a group of proposed measures that I believe are pragmatic and straightforward to implement. These are based on my experience as a senior leader at Facebook in these areas. My goal in all this, as a father and as an engineer who has worked on these problems for many years, is to help regulators, policy-makers, academics, journalists, and the public better understand how companies think about these problems and what it would take to address them. I also want to create a meaningful increase in support for the companies' integrity, trust, and safety teams. I am not selling anything, nor will I be looking for future work in this field.

This is my statement of retirement from the technology industry. Any work I do in the future to support regulators or others committed to reducing harm on social media will be pro bono.

From 2009 to 2015, I was the senior engineering and product leader at Facebook, responsible for its efforts to keep users safe and supported. I led the Protect & Care group, focusing on three main areas: “Site Integrity,” where we combated attacks and malicious behavior; “Security Infrastructure,” dedicated to building resilient systems and ensuring compliance; and the “Care” team, which created tools for Facebook users and for internal customer support. Additionally, I managed the development of child safety tools.

Across these domains, I managed the combined effort of engineering, product, user research, data, and design. This role involved regular strategic product reviews with the Facebook executive team: Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, and Chris Cox. Whenever significant issues arose involving engineering security, site integrity, child safety, or care, I was one of the key people that the executive team worked with. I supported them by overseeing investigations, crafting responses to external enquiries, and coordinating engineering and product changes where needed in those areas. Additionally, I was the manager for Facebook’s “Product Infrastructure” team, which built critical parts of Facebook’s product engineering frameworks. I was recruited to Facebook from Yahoo! where, after many years, I had become the company’s leader for information security.

While leading Facebook’s Protect & Care group, I spent much of my time making it easier for people to report issues they had when using the product. This included building tools to make it easier to report problems and creating survey tools so the company could better understand user experiences, including satisfaction with the service and its features (as well as building tools specifically to help teens, with the help of academic experts). By the time I left in 2015, after six years at the company, we had successfully built numerous systems that made our products safer to use.

I left—in part—because I wanted to spend more time with my family, especially as my daughter was entering her teenage years. Like most young Americans, she is an avid social media user (mostly Instagram and Snapchat). It was through her eyes that I was able to get an up-close look at the teen’s daily experience with these products. Despite the benefits social media brought her, she frequently had to deal with awful problems. My daughter and her friends—who were just 14—faced repeated unwanted sexual advances, misogynistic comments (comments on her body or ridiculing her interests because she is a woman), and harassment on these products. This has been profoundly distressing to them and to me.

Also distressing: the company did nothing to help my daughter or her friends. My daughter tried reporting unwanted contacts using the reporting tools, and when I asked her how many times she received help after asking, her response was, ‘Not once.’

Because of these experiences and a desire to understand why my daughter was not getting any help, I returned to Facebook, this time working with Instagram as an independent consultant focusing on user “well-being.”

What I found was extremely disturbing. I discovered that the issues my daughter encountered were happening at an unprecedented scale all over the world. Here’s just one shocking example: Within the space of a typical week, 1 in 8 adolescents aged 13 to 15 years old experience an unwanted sexual advance on Instagram.1 When you multiply that out by the hundreds of millions of teens who use Instagram globally, it means that Instagram hosts the largest-scale sexual harassment of teens to have ever happened.

I learned that little is being done to fix this and that all of the tools to help teenagers that my colleagues and I had developed during my earlier stint at Facebook were gone. People at the company had little or no memory of the lessons we had learned earlier or of the remedies we put in place.

While the people working directly on these issues at Instagram were skilled, committed, and wonderful, they were faced with a leadership culture that was unwilling to address the many different harms that people were experiencing.

When I had a full, accurate picture of the scale of harm occurring to teens on Instagram, I sent out an email, including detailed data, to Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, Chris Cox, and Adam Mosseri, with whom I had worked for years. Chris Cox was aware, within statistical margin, of all the numbers. Sheryl Sandberg wrote back, saying that she was sorry my daughter had these experiences and that she knew how distressing they could be for a young woman. I met with Adam Mosseri, who understood and agreed with the issues I raised and spoke about the importance of giving a feature to a teen girl she would find helpful and rewarding when she got an unwanted advance. Mark Zuckerberg did not respond, unlike every other time I had brought material harm to his attention. None of them took any action to address the harm teens are experiencing.

Image. Harms experienced by Instagram users by age. From BEEF (Bad Encounters and Experiences Framework) survey.

It was this failure of the leadership team that led me down the path by which I ultimately became a whistleblower. I didn’t want to harm the company. I wanted to help the company to fix a serious problem. I am writing this so that people can get an accurate understanding of a teen's experience with social media and talk about measures that, I believe, could make a big difference.

Social Media Companies Will Not Change On Their Own

I am not the only one to blow the whistle. In recent years, repeated examples of harm that have been enabled by Meta and other companies have come to light through whistleblowing, outside research studies, and many stories of awful experiences with these products. Whenever such reports emerge, Meta’s response is to talk about the ‘prevalence’ of these problems and its investment in moderation and policy, as well as ‘features’ that don’t meaningfully reduce the harm shown by its own studies. But there is a material gap between their narrow definition of prevalence and the actual distressing experiences that are enabled by Meta’s products.

For example, in Meta’s transparency center in 2021, they stated that the ‘prevalence’ of bullying and harassment on Instagram was .08% (i.e., of 10,000 views, 8 witnessed bullying content). But this number misrepresents the number of people who witness bullying and harassment. During the same time period, 28% of people reported witnessing bullying and harassment (in the last 7 days). Bullying and harassment are a much more significant problem than Meta’s transparency numbers suggest. Even worse: Meta has no transparency for unwanted sexual advances other than what got published through my whistleblowing.

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg and other company representatives did not address the harms being discussed publicly in their testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee and to other outlets. Instead, they minimized or downplayed published findings and the results of their own research.

Given the companies’ longstanding reluctance to address these problems on their own, I believe that the only way things will get better is if the companies are forced to act through government regulation.

What Regulators Need to Understand About Social Media Companies

Social media companies, and Meta in particular, manage their businesses based on a close and ongoing analysis of data. Nothing gets changed unless it is measured. Once Meta establishes metrics for anything, employees are given concrete incentives to drive those metrics in the direction the company deems useful and valuable. Metrics determine, for example, how many people work in a given department. Most of all, metrics establish the companies’ priorities.

This is why it is critical that Meta and other social media companies establish metrics and gather data on people’s actual experiences of receiving unwanted contact and distressing content. When outside critics point to harm caused by Facebook or Instagram, I have often observed Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his managers try to change the conversation to the things they measure. If the problems identified are not problems that the company’s systems are designed to detect and measure, managers literally have no means to understand them. Zuckerberg is unwilling to respond to criticisms of his services that he feels are not grounded in data. For Meta, a problem that is not measured is a problem that doesn’t exist.

I have specific recommendations for regulators to require any company that operates social media services for teenagers to develop certain metrics and systems. I believe it is necessary for outsiders–that means governments and regulators–to step in and require metric-based goals based on the harm that teenagers experience. These approaches will generate extensive user experience data, which then should be regularly and routinely reported to the public, probably alongside financial data. I believe that if such systems are properly designed, we can radically improve the experience of our children on social media. The goal must be to do this without eliminating the joy and value they otherwise get from using such services.

I don’t believe such reforms will significantly affect Meta and its peers' revenues or profits. These reforms are not designed to punish companies but to help teenagers by creating a safer environment over time.

Some things that every parent should know

Reforms will take time, so I want to first speak to other parents who may be struggling with these issues. If you’re the parent of a teenager, it is important for you to know that there is a high likelihood that your child receives unwanted contact and content, at least occasionally. The stories you see in the news of teens committing suicide because of experiencing bullying, sextortion, or other cruelties––those things happened to the children of diligent parents. The most important thing you can do for your child is to make it easy and safe for them to talk with you about whatever they are experiencing or whenever they feel they have made a mistake.

Ask your teen about content they saw online that they did not want to see. Ask them about whether they have received messages that made them uncomfortable. If possible, talk with them about unwanted contact online, requests for nudes, or requests for sex. Most teens can readily describe bad things that have happened to them online.

If you want to get a sense of how many teenagers are impacted, I suggest you ask teens you know to tell you about their online experiences, and those of their friends. You will likely hear distressing stories and perhaps a resignation among teens that “this is just the way things are…”

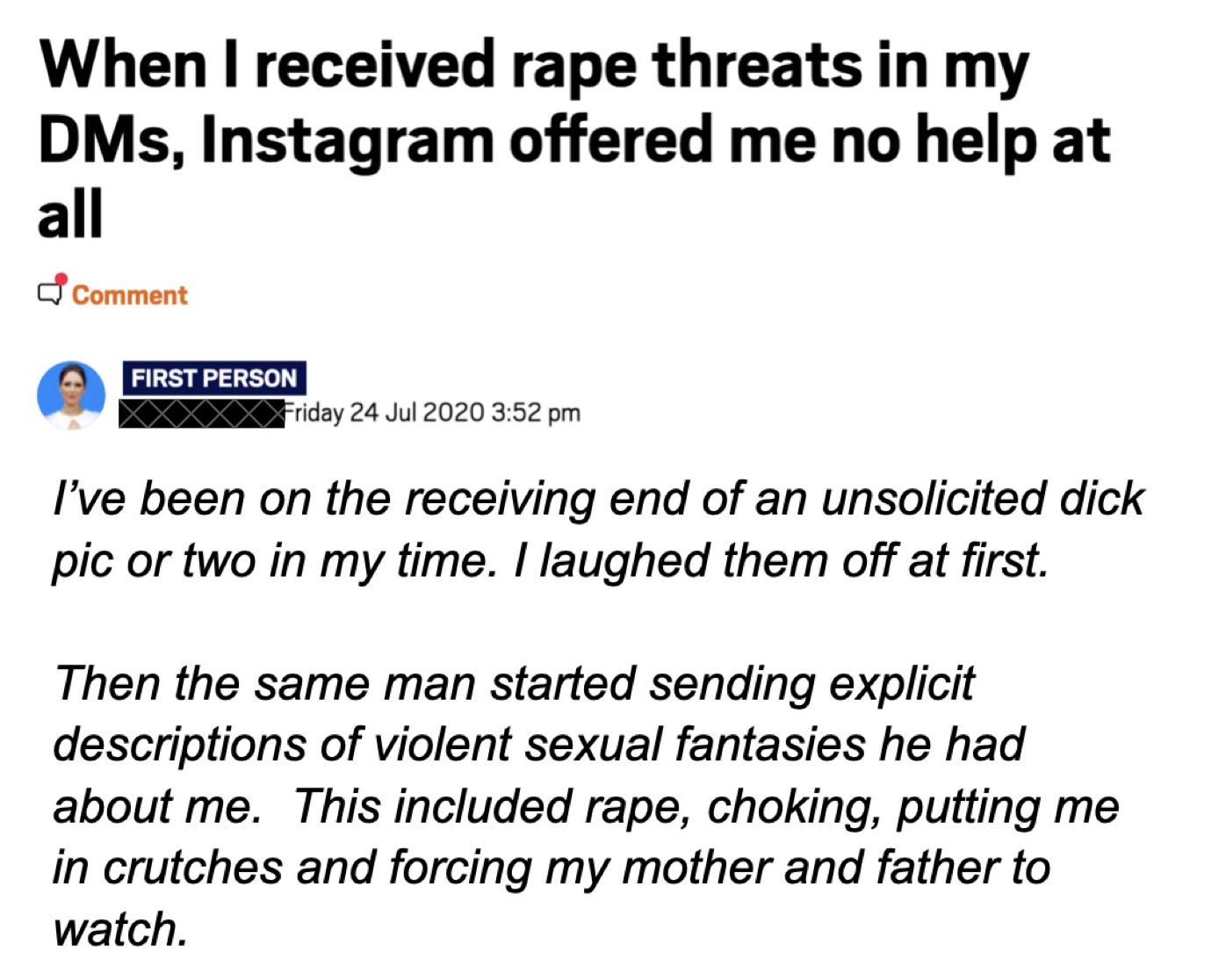

Image. Anonymized user feedback. From Bad Experiences Measurement.

But things do not need to be this way. It is not acceptable that this is the way things are.

I’ve approached my responsibility as a parent to teens by being aware of what my kids are doing and knowing who they are spending time with. Most importantly, I did my best to make it safe for them to bring up anything that they do or that happens to them online.

Imagine if something bad happened to your kid at a school. Who would you want them to turn to first? Should they come home and tell you about it? Or turn to a teacher or someone in the school for help and then let you know? It may depend on the context, but the same range of options should be available online. What should they do if the school is not doing anything to help them? If sexual harassment and bullying were frequent there, wouldn’t you hold the principal accountable? Isn’t it the administration’s job to ensure that the kids under their care have processes and tools to help them cope and adapt when bad things happen?

Ultimately, it should be the responsibility of social media companies to create a safe environment for our kids. We expect this from every business that creates a place where teens hang out–especially a business that works so hard to lure kids in and then holds onto them for as much of the day as possible.

I oppose censorship

It is essential to note that for all of my suggested reforms, I’m not advocating any censorship or the deletion of content. I believe in the importance of free expression. However, free expression should not allow an individual to send someone direct messages (DMs) that threaten or proposition you. I believe the same principle should apply to people’s posts. A teenager should be able to have their posts be a safe space for them, and this requires tools to deal with misogynistic or hateful comments that don’t rely on reporting.

Underlying this approach is the belief that in order to reduce distressing experiences for people, the most important area social media companies should work on is social norms. The current approach, based on setting legalistic definitions within policies and reactively removing content, is not sufficient. More importantly, it does not address the majority of the distressing experiences people face. What must guide the design of features to make people feel safe with each other in social media should be the actual experience of users.

Social media is unlike most environments where people spend time because, in general, it does not have sufficiently accepted and maintained social norms. What makes a workplace, school, or park feel safe, by contrast, is mostly not the policing but rather how people just know how to behave. We would never tolerate routine sexual advances to teens at our local supermarket. However, on Instagram, Facebook, and other social services at the moment, we completely tolerate that happening and give teens no way to report it. This must change.

If, as you review these documents, you find inaccuracies in my data, flaws in my reasoning, or believe some relevant information should be included, or if you would like to contact me about any of these issues, please go to www.arturobejar.org.

My goal is to be accurate and clear in the service of people who are dedicated to protecting and caring for others online.2

Below are some other related documents and explanations I have prepared

I wrote a series of essays with the goal of giving concrete and pragmatic recommendations. They cover some common misunderstandings about how harm plays out on social media and are intended to give regulators, journalists, academics, and people in the industry tools to support their work in reducing harm.

Why social media’s current approach to policy and enforcement doesn’t work.

Harmful content must be understood from the perspective of the person who is affected.

Good questions for the press and others to ask social media companies.

Some examples and notes for Integrity and Trust and Safety workers.

The statistics come from the BEEF (Bad Encounters and Experiences Framework) survey, done by Instagram’s user research team, which surveyed hundreds of thousands of people worldwide. The study was recently published as part of New Mexico’s litigation against Meta. To see the extent of harm, by age, for different harms, look at page 21.

Everything covered in these documents is the result of my thinking about these problems after I left Facebook. When I refer to results or observations from the Compassion work we did at Facebook, the data and results were presented publicly. The recommendations I make here are pragmatic, based on experience and an understanding of these companies and systems. They could be readily implemented.

Thank you for the comments and feedback. I wanted to address some of them:

1. As Greg Baer wrote, love your kids unconditionally and make it as safe as possible to tell you anything.

2. If you can - don’t give your kids social media until they are 16. Besides the addiction and other issues well documented here, if you look at the table of harms you’ll see how tragically likely they likely have a harmful experience. I waited until my daughter was 14. Had I know then what I learned I would have waited until she was much older. At least 16 or 17.

3. I’m not recommending reporting for messages, or to hire anyone to do message report reviews. The proposal is detailed in the other notes. It is a button to flag a conversation as an unwanted advance. The content does not matter.

I worked in IT for many years as an engineer. Banning pornographic content hasn't been a technical knowledge problem for at least 20 years. It has been a political will problem, like this is.

So change the incentives.

Fines and bad PR won't do it. Whistleblowers won't do it. Throw some Silicon Valley tech CEO's in prison for 30 days (a US attorney can find a charge). Indict a major venture capital firm for facilitating sexual trafficking of minors. There will be AI-driven scanning of all uploaded content implemented within 2 weeks and electronic age verification and cordoning off of minor from adult spaces within 2 more.

I greatly appreciate this former manager's courage for speaking out. But his solutions are woefully inadequate.