Growing up Online Nearly Killed Me

A dual narrative of mother and daughter about a new school, new phone, and online grooming

Introduction from Zach Rausch:

One of the fastest-growing dangers facing young people online is sexual extortion. Unredacted lawsuits from Snapchat reveal that the company receives roughly 10,000 reports of sextortion every month, a figure that their researchers say represents only a fraction of the abuse occurring on their platform. Other platforms face similar problems. None have been able to contain it.

Today we are sharing the story of Roxy Longworth, a young Gen Z woman from London who was groomed, sextorted, and publicly shamed by older classmates beginning at age 13. It is a devastating testimony about an intensely traumatic experience — online and offline — told from both Roxy’s perspective and that of her mother, Gay.

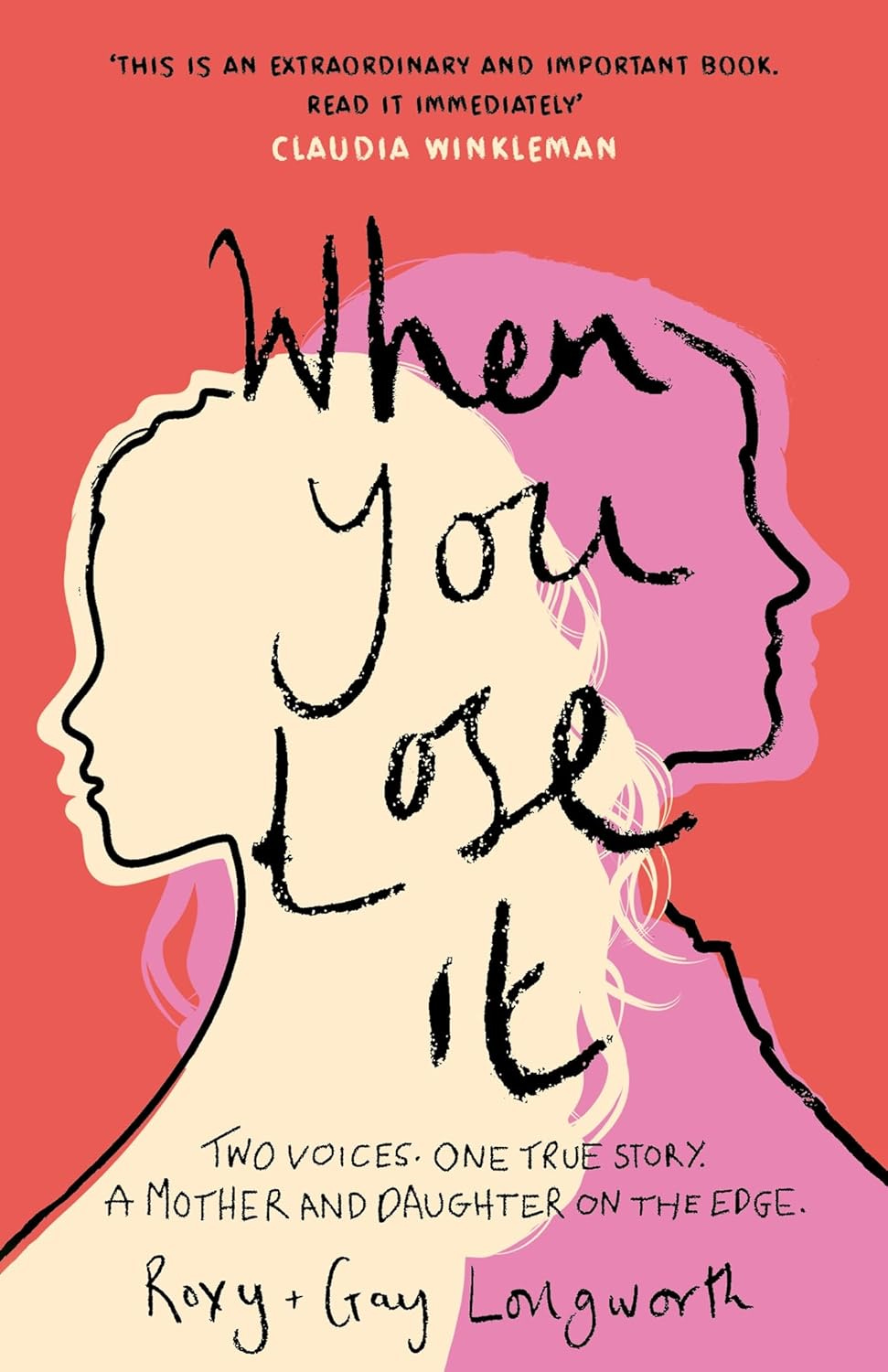

Although the severity of Roxy’s experience is relatively rare, it shows how ordinary digital interactions can snowball into something no child should have to endure. Roxy survived because of her relationship with her mother. The daughter-mother story, told together in When You Lose It, is ultimately about repair, honesty, and the strength of a parent-child bond in the aftermath of trauma.

This essay offers their dual narrative: how Roxy’s life changed once a smartphone was in her hand, what happened when the worst occurred, and how mother and daughter found a path forward together.

– Zach

Growing up Online Nearly Killed Me

By Roxana Longworth and Gay Longworth

Gay

Roxy is 23 now. She is about to start a graduate training program at a top strategy consulting firm — 0.3% acceptance rate. At 22, after graduating from University College London (UCL) with a degree in Maths, Neuroscience, and Statistics, she launched a campaign to end young people’s experience of online harm: Behind Our Screens, on Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg. At 20 Roxy became an ambassador for the the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC). Our book, When You Lose It, was published when she was only 19-years-old.

Am I a proud mother? You bet I am, but that’s not why I list her extraordinary achievements in this introduction. It is because there was a time when I feared every day for her life. At 13 she was groomed, coerced, and blackmailed online — and the psychotic episode that followed nearly killed her. At 14 she thought her life was over, she had nothing to live for, and the voices in her head told her she was the “stupid little slut” who had ruined her life. A few more pills, a deeper cut, a slight tip of weight over the windowsill. If I had been too slow to grab the car door when we were driving at 60mph. If a car had come the time she lay down on a blind corner. Any one of these could have ended her life. Had that happened, her story would have ended at age 14, and ours with it.

Roxy

I can’t decide if I find it more uncomfortable to hear my mum talk about my achievements, or my nudes.

When we were taught about “online safety” at school, it always felt completely unrelatable. Teachers didn’t get it, and the information felt so far from the reality of our experiences. The case studies seemed extreme, and honestly, I thought there was no way I would ever be the person stupid enough to end up in those situations. There was no way this stuff would happen to me.

When boys started messaging me, I was embarrassed by how much better their attention made me feel. I was ashamed that I craved that validation. I was 13 when a 17-year-old boy at my school messaged me out of the blue on Facebook Messenger and asked to move the conversation to Snapchat. He was older, popular, and attractive — and I was flattered. I quickly became addicted to the feelings I got when his messages arrived. Within days he was asking for pictures, and when I said no, he would stop messaging me for a few days. The rejection cut deep. Which I guess it was intended to do. He said that if I didn’t send them, he’d tell everyone that I was frigid and boring and then nobody would want to talk to me. But when I did send them it was never enough. Night after night he demanded a more explicit photo to keep him interested. Every night I went through the same cycle: an amazing high when he told me I was attractive, then a crash into intense self-disgust, self-loathing, and crippling shame.

Gay

Roxy got a phone when she was 13, and almost immediately battle lines were drawn. Just managing the hours was a challenge, let alone the content. The excuses were always just plausible enough: I need it for school, I need it to make a plan, I need it to sleep. When she was younger, story CDs soothed her reluctant brain to sleep, but now there was Audible. I lost every discussion. We weren’t at the fighting stage yet.

As one of the youngest students in her year she’d always been playing catch up. As she approached 14 and her friends turned 15, her bike gathered dust while boys and push-up bras took over. I tried to stay connected and offered advice about alcohol and drugs as she started going to parties. I was clear: don’t do either, but if you’re ever in a situation where things get out of hand, you can call me, day or night, and I will come to your rescue, no questions asked.

I wish, how I deeply wish, I had said the same about her online world. But as far as that was concerned it was just a long list of “don’t”s. When her mood worsened, I was helpfully informed that this was only the beginning — the dreaded teenage years had arrived, like an insatiable black hole sucking my child into a place I could not follow. So when Roxy retreated further, became ultra-secretive, and wouldn’t look me in the eye, I thought, “Here we go, Kevin the Teenager has moved in.”

Roxy

I stopped sending photos because it all got to be too much. It genuinely felt like what I imagine weaning yourself off a drug would feel like. Towards the end of the summer holidays I was beginning to feel like myself again — until I got a message from a different 17-year-old guy at my school. He asked for nudes, and when I ignored him, he sent four photos of me that he already had. He said he would share them around the school if I didn’t comply. My entire world collapsed.

This guy, whose name I hadn’t even known until that day, owned me. I dreaded each message, sending whatever he asked for so he wouldn’t spread the photos, all while trying to keep it a secret from my family. You know how mums have that weird intuition? I genuinely believed that if I made eye contact with her for too long, she would know. So, I avoided her as much as possible. Eventually I had to block him on everything because I couldn’t send the horrendous video he wanted. Then the waiting game began.

Gay

I was called into the school for “a word.” In fact, it was seven.

“Roxy has been sending photos to boys.”

I was left to fill in the blanks. Scrambling for understanding, I told them what I thought I knew. It turned out I knew nothing — nothing helpful anyway. And Roxy wouldn’t, or couldn’t, expand. If we had been able to have a meaningful (or better still, mediated) conversation with someone who understood the power dynamic between victim and perpetrator, we might have been able to work out what had happened and help Roxy before anything got worse. Instead, things got far worse.

The school laid the blame firmly at Roxy’s feet while urging us to “move on” as soon as possible. I now believe this was for their reputational benefit. The most destructive outcome was that it pushed Roxy into a downward spiral of self-loathing and turned us against each other at the moment we most needed to be a team.

Roxy

He sent them all around the school, and my first week of Year 10 was spent watching the photos spread rapidly. My friends stopped speaking to me, and boys shouted out of windows asking me to send them photos next. I was called in by the school and told that “luckily for me, they would not be contacting the police.” I was punished for breaking the school’s tech rules. That felt completely fair to me. In my head, it was all my fault.

I thought I wasn’t being punished enough, so I began punishing myself. I started cutting, making myself sick after meals, and stopped sleeping. The anxious voice in my head telling me I was a disgusting slut got louder and more controlling until I was literally hearing voices everywhere, telling me how disgusting I was, that I wasn’t safe, and that nobody wanted me here anymore.

Gay

I dialed 999 to report Roxy missing. While the search continued, a policeman explained why reporting “sextortion” is so important. She was the victim, not the perpetrator, and it was vital she understood that so she didn’t internalise the shame. He left me with no doubt that shame kills.

That compassionate police officer told me that a week earlier he had been called to the house of another 14-year-old girl. Almost exactly the same experience — older boys, photos, blackmail. But they couldn’t revive the poor child. I think of that girl often, though I never knew her name. Her story ended at 14, and it should not have. I wonder, as in our case, if nothing happened to the boys.

The police found Roxy, which makes us one of the lucky families. But as her mental health continued to deteriorate, my attention was pulled elsewhere as her dad and I mistakenly became the focus of a social service investigation because our daughter had run away. While that unfolded, Roxy became more frightened, more confused, and stopped sleeping. Within days the voice she’d been hearing became voices, then the voices became “people.”

I discovered they were “people” because one evening, acting on a hunch, I went into Roxy’s room and found her leaning precariously out of the window. Her empty bedroom was “too crowded,” she told me, before I managed to coax her back in. We lived with those sinister, name-calling, persuasive “people” for a long time.

It took a psychiatrist to point out the obvious: her inner critic was mimicking and amplifying the name-calling and slut-shaming she’d endured at school.

Roxy

There was a kind older girl at school who had been through a very tough time herself. She gave me a journal and told me that writing things out had helped her. I am thankful to her, because while what I wrote is impossibly hard to read, without those words on the page I would barely remember the months when I was ill. Perhaps that’s the point.

The psychosis protected me from the bleakness of my reality, but my family remembers it all. At one point I regressed to my much younger self and spoke in a childlike voice. The psychiatrist was pleased — it was a sign my brain had taken me to a safer place where I could recover. My sisters suddenly had a new “younger sister” in the house.

For me, coming out of psychosis many months later was almost worse, because my life was in pieces. No, it was worse than that, my sisters were busy at school, always singing or swimming or hanging out with friends. I felt I had no life, and no hope of ever having one. Just me, my mum, and our dog — day in, day out — shuffling like a geriatric through my teens. Sometimes it felt easier to think, “If I could just go to sleep. Eternal sleep.”

Gay

Roxy was finally placed on one-to-one care in a psychiatric unit, and then on suicide watch at home with me, 24/7, until the right antipsychotic medication was prescribed and finally took effect.

Even then the situation was precarious, because when Roxy was no longer psychotic, she could see with the full horror of clear thinking the desolation of her life. Real recovery meant not just staying alive, but being able to live a meaningful, happy life while holding those ruined years with compassion for all that was lost.

That is very hard. It took a long time. I know we both still have moments of total desolation and utter rage, but we plough on — because we also know we have a great deal to be grateful for. One another, for a start.

Roxy

During the Covid-19 lockdown, my mom and I were effectively back one-to-one, still unable to speak about what had happened. I spent the years from 15 to 18 living in a self-imposed miserable, lonely bubble. I moved to another school but avoided speaking to anyone because I was afraid of their questions. I lived in terror of those photos following me, so I put my head down and worked obsessively. I was unable to look at myself in the mirror because I was so disgusted by the person who looked back.

My mum and I grew further apart because of the complete lack of understanding about what the other had experienced. We couldn’t have the conversation we desperately needed to have, so we wrote to each other instead.

Those letters became the interwoven dual narrative in our book, When You Lose It. We wanted to help other people. But honestly, by finally having that “difficult conversation” through letters and the book, we healed our very broken relationship.

Gay

According to a recent article by the BBC, sextortion — sexual extortion — is one of the fastest-growing online crimes. Teenagers are scammed into sending intimate photos or videos to criminals pretending to be young girls or boys interested in them. When the threat of exposure is used to blackmail them into doing whatever the blackmailer wants (most commonly sending money), the children, fearing the photos will be shared with their contacts, in the worst cases, take their own lives.

The National Crime Agency receives over a hundred reports of this nature a month and no doubt, there are hundreds more that go unreported. In fact, internal emails from within Snapchat revealed that they receive 10,000 reports of sextortion every single month. I don’t think it is unreasonable to ask the tech companies to do more to protect children from this ever growing crime.

Roxy

The part that I struggle the most to think about is actually the years after. I spent the rest of my teenage years isolated and ashamed of “what I had done.” I avoided meeting anyone new because I was so scared of being asked questions about the past. I was so disgusted with myself that I wore overly baggy clothes and couldn’t look in the mirror.

I felt like the only person in the world “stupid” enough to ruin her life this way. But when our book came out, I received hundreds of messages from people who had seen or experienced things online that left them feeling ashamed and alone. It made me so sad to realise there were kids sitting in their rooms feeling the same isolation I had felt.

I started Behind Our Screens because I know what it feels like to suffer in silence, weighed down by shame. Too many young people are still carrying that alone. This campaign is about showing young people that they can talk openly about what they are experiencing and how it makes them feel. We are turning those hidden experiences into action.

By amplifying youth voices, we are sparking honest conversations and pushing for change in education, policy, and tech — so the internet becomes safer, kinder, and more human for the next generation.

I feel really lucky that I made it through, and I’m proud of how Behind Our Screens is helping others. There are still moments that are cripplingly sad. I wish that none of this had ever happened. The shame sits heavily in my chest, and it is easy to slip back into that place of self-loathing. I have to remind myself constantly that it was not my fault. The thought that other young people are suffering this very same crime daily is devastating to me.

It’s something we all need to put an end to.

So, did anyone take legal action against those young men monsters?

I despair that in the 21st century a 13-year-old girl still takes the rap for the sexual bullying and manipulation of much older boys (almost men). When will we ever leave the Dark Ages?