A Flawed Absolution for Smartphones

No, the Life in Media survey did not really show that 8-year-olds benefit from owning smartphones

Foreword from Jon Haidt and Zach Rausch:

Over the past two weeks, we've received more than a dozen emails from parents puzzled by a recent Tampa Bay Times op-ed titled, “Kids having smartphones is likely fine and may even be beneficial.” The piece draws on findings from the new Life in Media survey, which surveyed 1,510 Florida tweens between the ages of 11 and 13. Two of the survey’s seven authors wrote the op-ed, which ends with this bold conclusion:

There’s nothing wrong with limiting smartphone use among kids … But don’t be made to feel guilty because you got a child as young as 8- or 9-years-old a smartphone. It’s likely fine, perhaps even beneficial. And we would need much more data to suggest otherwise.

This is an extraordinary claim—and one that runs counter to our recommendations that parents should delay smartphones until age 14, and social media until 16. So we took a closer look. We asked David Stein, author of The Shores of Academia and collaborator with our Tech and Society Lab, to help us analyze the op-ed and the Life in Media survey.

As you'll see, the claims in the opinion piece are repeatedly undermined by findings in the survey report. In fact, as Stein shows, using their own results actually strengthens the case for delaying smartphone access.

– Jon and Zach

A Flawed Absolution for Smartphones

Introduction

Recently, an opinion piece titled Kids having smartphones is likely fine and may even be beneficial endorsed the idea of parents giving smartphones to children as young as 8 years old.

The authors, a professor along with a graduate student from the USF Department of Journalism and Digital Communication, also specifically criticized the views of Jonathan Haidt, as indicated by the subtitle of their essay: The findings from USF researchers challenge some previous work, including parts of Jonathan Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation.”

The opinion piece is part of a string of public statements by professor Justin D. Martin in which he absolves smartphones of any role in the deterioration of adolescent mental health that began in the early 2010s (when teens got smartphones) and instead encourages parents to give young children a smartphone of their own.

The opinion piece provides an opportunity to examine Martin’s arguments as he and his colleague Logan Rance attempt to justify their dismissal of concerns about smartphone impacts on the wellbeing of kids.

Martin & Rance base their essay on a survey they conducted (with other researchers) among Florida kids aged 11 to 13. They compared measures of wellbeing among the 78% of kids who own a smartphone with those of the 22% who do not own a smartphone. They found similar or slightly better wellbeing, in most measures, among the kids who do own a smartphone.

They conclude, on this basis, that smartphone use and ownership by young kids is likely harmless.1

In this critique, we will describe three fundamental flaws in their methodology:

Their argument ignores the actual usage of smartphones and similar devices, especially tablets.

Their argument ignores the substantial influence of demographics such as parental income and education.

Their argument ignores reverse causation as a partial explanation of the results.

In fact, if properly analyzed, the wellbeing results in the survey may be consistent with smartphones being harmful because the small 22% ‘non-owners’ group appears to be largely made up of kids who:

Use smartphones frequently anyway

Own or use tablets that facilitate harm in similar manner to smartphones

Are disproportionately from demographic groups that have poor wellbeing

Do not own a smartphone precisely because their wellbeing is already poor

Once these factors are properly taken into account, smartphone use may be associated with lower well-being than would be expected if smartphones are harmless – thus flipping the relationship between smartphones and wellbeing that forms the basis of the absolution from Martin & Rance.

Life in Media Survey

Martin leads a USF project called Life in Media that conducted the survey in question. He is also the lead author of the survey report, titled The Life in Media Survey: A baseline study of digital media use and well-being among 11- to 13-year-olds.

The Life in Media Survey report did not release all the results from the survey – instead, the authors revealed only a subset of the results. A lot of important information, such as how smartphone ownership differs between girls and boys, has been omitted from the report.

Most importantly, the Life in Media Survey report includes no indication that any of the outcome comparisons were adjusted for demographic factors – apparently not even for gender and age. Such adjustments are prerequisite to any sensible discussion of potential causal links. The conclusions of Martin & Rance about smartphone use by kids will remain speculation impossible to evaluate until the Life in Media Survey data is released to allow proper statistical analysis.2

Three Presumptions

Martin & Rance base their conclusions about smartphones primarily on the following assertion about the Life in Media survey:

On almost every health and wellness measure we fielded, children who have their own smartphones fared significantly better, or at least no worse, than kids who don’t have their own smartphones.

The survey results have not been released in full, but we will accept this statement as accurate for the purpose of this critique. Martin & Rance then take it for granted, without offering any further analysis, that this finding means that smartphone use by young kids is most likely harmless.

There are, however, at least three major presumptions required for such reasoning:

The two groups do differ substantially in the harmful use of smartphones and similar devices.

The two groups do not differ substantially in wellbeing for reasons other than the use of smartphones.

Smartphone ownership is not substantially influenced by the wellbeing of the kids.

The first assumption is necessary if smartphone ownership is to be a sensible criterion for the evaluation of smartphone usage harms. The second assumption is necessary in order to rule out the influence of factors unrelated to smartphone use. The third assumption is necessary in order to rule out ‘reverse causation’ as partial explanation of the results.

Do these requirements hold?

Three Fundamental Flaws

None of the three presumptions seems plausible in view of the evidence.

In Florida, the survey results revealed that the use of smartphones by kids aged 11 to 13 is nearly universal (over 90%) and that a majority owns a tablet and a vast majority use a tablet. The consideration of tablets is important because these devices are similar to smartphones in the ways they facilitate harm.

This means that Martin & Rance may be comparing kids who own a smartphone with those that don’t own one but either own a tablet or else frequently use a smartphone or tablet that belongs to someone else (such as their parents).

As we will see, what the kids reported about how technology impairs their lives shows that there appear to be no substantial differences between the two groups in the degree to which smartphones and tablets are used in harmful manner.

The survey results therefore undermine the credibility of the first requirement, namely that the two groups must differ substantially in the harmful use of smartphones and similar devices.

The second requirement – that the two groups must not differ substantially in wellbeing for reasons other than the use of smartphones – is violated because, in the survey, kids with higher-income and better-educated parents seem to have by far the worst wellbeing outcomes and, at the same time, the lowest rates of smartphone ownership.

Once these and other demographic factors (like gender and age) are properly taken into account, it may easily turn out that smartphone owners have worse wellbeing outcomes than would be expected in view of their demographic characteristics and circumstances.

Finally, Martin & Rance never explain, in the opinion essay, why kids who do not own a smartphone are much more likely to be cyberbullied. The most plausible explanation – expressed by the authors of the Life in Media report – is that parents of victimized and troubled kids are trying to protect them by delaying the time when they get their own smartphone. That is a ‘reverse causation’ violating our third requirement.

Since the three requirements do not hold, then neither does the reasoning of Martin & Rance.

Evidence

Let us now look closely at some of the released Life in Media Survey results that are particularly relevant to the arguments by Martin & Rance about smartphone impacts on the wellbeing of kids.

Smartphone Use

Psychologists are mostly concerned about the usage of smartphones by kids, and this does not require ownership. This is especially true of young adolescents, who need not ‘own’ a smartphone to use one frequently.

The results of the Florida survey of kids aged 11 to 13 illustrate why this is a valid issue: although 22% of kids did not own a smartphone, only 8% did not use a smartphone.

We can see the details in Figure 1.2 of the report:

So the majority of ‘non-owners’ among kids – nearly two thirds of them in fact – actually do use a smartphone.

Comparing kids who own a smartphone with those who don’t own one but use one anyway is not a reliable method to evaluate the harms of smartphone use.

It makes especially little sense when used to dismiss Haidt’s concerns, as Martin & Rance do, since Haidt is primarily concerned about the usage of smartphones by kids, not its mere ownership. Haidt does not say it’s OK for kids to frequently use a smartphone as long as they do not actually own the phone.

Furthemore, the survey collected estimates by kids of the time they spend daily using a smartphone. The Life in Media report, however, does not provide any information of the relationship between smartphone time and wellbeing outcomes.

Tablet Use

It is also important to consider the use of similar devices – especially tablets, which, like smartphones, are mobile digital touchscreens.

The use of similar devices can be seen in Figure 1.9 of the report:

Even laptops and computers can facilitate plenty of access to social media, which is likely one of the main pathways to harm on smartphones.

Tablets in particular, given that they are small enough to be carried out of the house or used in bed, can facilitate harm in very similar ways to those on smartphones.

Haidt is equally concerned about tablets as he is about smartphones, as can be seen in the following quote from an interview with Ezra Klein:

So in the book I say there are four norms [so we can] roll back the phone-based child. The first is no smartphone before high school. Do not give your kid a touch screen. This includes an iPad. Don’t give them their own touchscreen before high school or age 14.

That Haidt is equally concerned about tablets is plain to see also in his book The Anxious Generation; consider, for example, the start of Chapter 6:

Alexis Spence was born on Long Island, New York, in 2002. She got her first iPad for Christmas in 2012, when she was 10.

What follows is a harrowing description of a mental tailspin facilitated by her use of Instagram on her tablet, ending with a hospitalization for anorexia and depression. No smartphone is mentioned at all.

And yet Martin & Rance rely on kids like Alexis – those who own a tablet rather than a smartphone – to argue that Haidt’s concerns about smartphones are misplaced.

What portion of the smartphone ‘non-owners’ either own or use a tablet is not revealed by Martin & Rance or by the report they helped write, but it is likely considerable given that 85% of kids in the survey reported using a tablet.

Note that the survey report reveals that children who own a tablet were more likely to report feeling depressed compared to those without a tablet (26% vs. 19%). Martin & Rance do not mention this in their opinion piece, even though 56% of the kids reported owning a tablet. Are they willing to conclude that tablet ownership is harmful, using the same logic they used for smartphones?

Demographic Differences

The report reveals that smartphone ownership is considerably less common among kids from higher-income families:

These results show that only about 16% of lower-income kids do not own a phone compared to 30% of kids from higher-income families. The ‘non-owners’ group is therefore disproportionately from higher income families.

At the same time, the report reveals that kids from higher-income families – as well as kids with more educated parents – are far more likely to agree that life feels meaningless: 31% in households making $150,000 or more vs. 10% in households making less than $50,000 and 29% among children of a college graduate vs. 5% among children whose parent has a high school degree or less.

These are vast disparities in this outcome variable.

Now if the group of kids without their own smartphone is dominated by children from higher income and well-educated families, and the children from such families have the worst wellbeing outcomes, then parental income and education levels could easily explain why kids without their own smartphone also have poorer wellbeing outcomes.

Note that, after announcing that kids without their own smartphone have mostly poorer or equal wellbeing outcomes to those owning a smartphone, Martin & Rance declare:

Money isn’t the reason for these findings; kids in low-income homes were significantly more likely to have their own smartphone than children from wealthy households.

This statement makes no sense if kids from wealthy households have by far the worst wellbeing outcomes.

There are additional demographics that may also play a role in the wellbeing comparisons relied upon by Martin & Rance.

For example, the survey report states that kids without their own smartphones were more likely to agree that life feels meaningless and that this is also true of boys when compared to girls. Now what if smartphone ownership is more prevalent among girls? The group without smartphones would then be dominated by boys, and since boys are more likely to agree that life feels meaningless, that too could explain the higher likelihood of this within the ‘non-owners’ group. The survey report unfortunately does not reveal the prevalence of smartphone ownership among boys versus girls.

Until the Life in Media data is released to allow proper statistical adjustments, we will not know to what degree demographics such as age, gender, or SES influence the comparisons that form the basis of the argumentation by Martin & Rance.

Problematic Tech Use

Does it matter if the vast majority of smartphone ‘non-owners’ among the surveyed kids actually uses a smartphone or tablet on a daily basis? It certainly does when Martin & Rance rely on this group in order to portray smartphones as harmless.

We only need to look at Figure 4.3 in the survey report to understand why this issue is important:

The kids who do not own a smartphone are just as likely as the kids who do to say:

I find it difficult to stop using technology, such as the internet or my phone, once I start

I don’t get enough sleep because I am on my phone or the internet late at night

I don’t do things I’m supposed to because I am using technology

I feel restless, frustrated, or irritated when I cannot access the internet or check my phone

There appear to be no differences between the two groups in how these digital devices dominate their lives.

Isn’t it therefore likely that most of these kids use smartphones or tablets as much as the kids who outright own a smartphone?

The authors of the Life in Media report address the results in Figure 4.3 as follows:

This pattern was almost consistent regardless of whether they own a smartphone. This parity may exist because it takes less than having a smartphone to experience the negative influence of media technologies. Among the kids who did not have their own smartphones, many of them reported that they share a phone with someone or regularly use someone else’s phone. Many kids without a smartphone also own, borrow, or share other digital devices— tablets, for example—years before they own a smartphone.

Precisely!

The Harmless Harms of Smartphones Mystery

The authors of the Life in Media report admit that the above figure (4.3) is troubling:

Overall, an alarming number of kids reported adverse effects of technology in their daily lives.

If digital technology impairs the lives of these young kids so frequently that the very report that Martin & Rance helped write calls this “alarming” – and since this applies to the 78% of kids owning a smartphone, then how can Martin & Rance conclude that smartphones are harmless?

That is a mystery.

Note that Martin & Rance did not have to explain this conundrum because they do not mention Figure 4.3 results in their opinion piece.

Martin & Rance could perhaps argue that these smartphones are safe because their harms are lesser than those awaiting kids who do not use smartphones. That reasoning, however, is contradicted by the parity of technological harms in Figure 4.3 between owners and non-owners. That means that smartphone harms are being evaluated by comparing one mix of technological devices with a slightly different mix of technological devices. That is not a valid methodology to decide if a product is safe – at best it might tell us that one mix of technologies is a bit less harmful than another mix.

Imagine a land where boxing is so popular that 90% of boys box and the rest kickbox. If you compare the risk of sports injuries between boys who box and boys who do not box, you are comparing boxing with kickboxing – not a sound method to decide if boxing is safe.

The Bullying Paradox

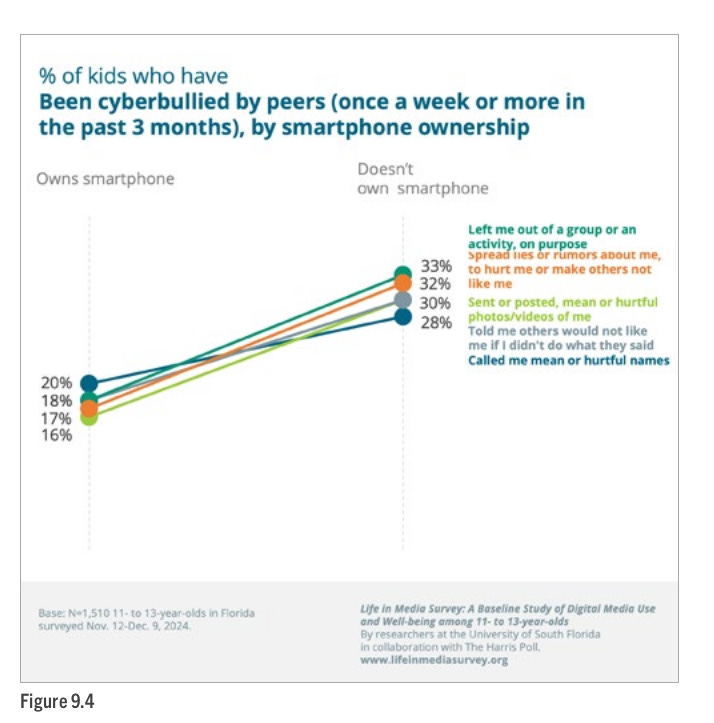

Perhaps the most unexpected result of the Life in Media survey is that kids without a smartphone of their own report considerably higher rates of being cyberbullied: “Kids without smartphones were much more likely—on some measures nearly 50% more likely—to report being cyberbullied than kids who own smartphones.”

Figure 9.4 shows this for various kinds of online bullying:

It is puzzling that Martin & Rance’s defense of smartphones relies in part on this result.

Martin & Rance mention being cyberbullied as a wellbeing outcome that they include in their argument that smartphones are safe. It seems Martin & Rance believe owning a smartphone somehow protects kids from being bullied.

Is that plausible? It is not.

First of all, most of the kids who do not own a smartphone either do have frequent access to a smartphone or own a tablet instead (often more expensive than a smartphone).

Second, a more plausible explanation is that parents of kids who have been bullied (online or off) delay giving their kids a smartphone of their own out of fear that this would make the bullying even worse. In other words, these parents may be trying to protect their kids precisely because they were already victimized, online or off.

It is more plausible that being bullied leads to delayed smartphone ownership than it is that smartphone ownership protects kids from being bullied.

The authors of the Life in Media report agree. In their commentary on the bullying paradox of Figure 9.4, they do not endorse the dubious possibility that smartphone ownership somehow prevents kids from being bullied. Instead, they argue that “parents of children who have experienced cyberbullying, or are most vulnerable to bullying, hesitate to give them a smartphone for fear of exposure to further cyberbullying.”

Precisely!

Reverse Causation

Since Martin & Rance count being cyberbullied as a wellbeing outcome, that means that the explanation of the cyberbullying paradox by the authors of the report is likely an example of reverse causation explaining one of the wellbeing outcomes.

Indeed the authors use the term “reverse causation” to label their theory. That means the Life in Media report directly contradicts one of the justifications given by Martin & Rance in their opinion piece.

Furthermore, the Life in Media report confirms that being cyberbullied is associated with other types of poor wellbeing: “cyberbullied children were much more likely than un-bullied kids to say they’ve felt depressed most days in the prior year, to say they often get angry and lose their temper, to say they find it hard to stop using technology once they’ve started, and to say that social media causes more harm than good.”

That means that the reverse causation explanation may explain many other wellbeing outcomes that Martin & Rance misinterpret as evidence that smartphones are safe––and even beneficial––for children.

Indeed the reverse causation is likely to occur generally whenever there is a problematic use of digital technologies by young kids – which in turn lowers the happiness of these kids – and so parents postpone smartphone ownership until the kids are more mature.

Smartphones Good, Social Media Bad?

After declaring smartphones to be harmless, Martin & Rance raise the following question:

So, if having a smartphone doesn’t contribute to ill-being among 11- to 13-year-olds, what does?

Their answer to this question is that the great culprit is public posting on social media!

Martin & Rance give no hint in their article of the fact that Jonathan Haidt has been one of the most prominent voices (along with Jean Twenge) warning against public posting on social media by adolescents, nor of the fact that this is one of the key themes of his book The Anxious Generation.

Furthermore, one of the four recommendations in the survey report that Martin & Rance helped write states the following:

This could have easily been written by Haidt. The risks listed above are indeed among the key reasons why Haidt warns against children obtaining social media accounts before the age of 16.

Conclusion

There are fundamental flaws in the argumentation by Martin & Rance that smartphones do not play a detrimental role in the decline of adolescent wellbeing and that it is safe to give kids as young as 8 a smartphone of their own. Similarly, there are serious flaws in their dismissal of Haidt’s concerns about smartphones. At the same time, the Life in Media survey results confirm earlier findings that social media use – especially posting – is associated with profound risks; however, appropriate statistical analysis is required to evaluate the data before we are able to undertake any further discussions of causality.

Martin & Rance also state: “We asked kids how old they were when they got their first smartphone, and we found no correlation between the number of years children have had a smartphone and anxiety and depression.” This argument is also subject to the flaws listed in this critique. Furthermore, the Life in Media report contains no specifics on how the correlation was calculated and why that one particular correlation suffices to evaluate the relationship between age of smartphone ownership and wellbeing.

I asked Martin if there truly were no controls at all applied to the wellbeing outcomes shared in the survey report, but my April 2 email inquiry remains unanswered.

Another flaw that we should focus on, is our overreliance on scientific data to lead our life decisions. We should not only rely on statistics to confirm that smartphones remove children from real life living, playing, and interacting, that they need to grow and thrive.

Did the authors disclose any potential conflicts of interest? Seems like a "study" that the tech companies would like to fund.