Intro from Jon Haidt and Zach Rausch:

In The Anxious Generation, we argued that smartphones and social media are significant contributors to the multi-national youth mental health crisis that began in the early 2010s. In Chapter 11, we showed that the harms of the “phone-based childhood” go far beyond mental health, and impact student learning and education outcomes, which have also been declining since the early 2010s in countries around the world. The rapid adoption of smartphones and their acceptance in schools has fueled distraction, cyberbullying, and conflict among students. Educators are dropping out in frustration, and a majority of them believe that phones in schools are impeding student learning and mental health — and they want stringent enforcement from school leaders. We’ve written extensively on this—most notably in The Atlantic—where Jon called for bell-to-bell phone-free school policies. Since the release of the book, we have seen extraordinary success, with states like Virginia developing a comprehensive bell-to-bell policy for every K-12 school in their state. If you are looking to implement (or want to get your kids’ school to implement) phone-free policies, our team has just released an easily accessible and comprehensive phone-free school toolkit exactly for this purpose.

Although we are thrilled by the progress that has been made, we have heard from teachers across the country that the phones are just the first step. They are also extremely concerned about the other kinds of technology that began to saturate the school day at the same time: 1-to-1 iPads, Chromebooks, and other forms of educational technology (EdTech).

When we wrote The Anxious Generation, we weren't entirely sure what the impact of EdTech is on student outcomes. Some of it seems useful, such as supplementing a class lesson with a Khan Academy lesson after school, for high school students. Other uses seem less clear, such as replacing a middle-school class orientation with QR code scans and videos.

So, what should the role of iPads, Chromebooks, or mobile education gaming be in the classroom? In an era when test scores are declining, how much have these technologies really contributed to student learning? Have the distraction effects of these devices overwhelmed the educational benefits? And at what age should these devices and programs be introduced?

To find answers to these questions, we invited Amy Tyson to write for us. Amy is a co-founder of Everyschool, an organization dedicated to making schools smarter, happier, and healthier through digital wellness. Amy offers a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape of screens in schools, addressing five major myths that fuel some of the device misuse and overuse in classrooms today. She also provides a clear, actionable roadmap for schools to adopt smarter, more effective technology practices that empower students to thrive in the 21st century.

— Jon and Zach

(P.S., We plan to present a variety of perspectives on this topic—let us know what you think about the role of EdTech in the comments, especially if you have evidence of its benefits.)

I founded Everyschool in 2019 with the mission to make schools smarter, happier, and healthier through digital wellness. At the time, the concept of "digital wellness" was still somewhat novel. We define it as an intentional state of engagement with the digital world that does not interfere with—but instead supports—mental, physical, and social health. I started Everyschool because I have come to believe that educational technology is not the panacea we’ve been told it is, and while some technology is transformative for some students, screens in schools have become yet another source of technology oversaturation in our children’s lives, often resulting in students being less smart, less happy, and less healthy.

I am a former child and adolescent therapist. My partner in Everyschool, Blythe Winslow, was a college professor and is a self-taught “techie.” Together, we’ve spent six years studying screens in schools, which includes the use of educational technology (or EdTech) and the use of recreational devices in schools (mainly cell phones by students). We’ve examined where research in education, child development, and mental health converge to understand how we can expose students to beneficial technology while protecting them from its harmful effects. We’ve spoken with educators, school boards, and hundreds of parents nationwide, all struggling with the same concerns. What we’ve learned has led us to conclude that many schools have not incorporated a research-based approach to implementing technology in education, nor do they acknowledge the potential costs of displacing traditional methods in favor of screens in schools.

On a personal level, I am a mother of four children who built a home across the street from a top-rated elementary school in a top-rated public school district—a school my own children do not attend after I got a close look at how technology is implemented there. When my oldest was entering Kindergarten, I began to hear rumblings in the neighborhood about the way technology was being utilized in the District. Parent concerns were varied, but a few issues surfaced repeatedly: the amount of time spent on digital games, the large amount of curriculum time spent on devices, students using iPads during downtime and indoor recess, and inappropriate content accessed on school-issued devices. From my years of experience as a therapist and my education in child development, what I was hearing didn’t align with what we know is best for developing minds and bodies. I started investigating, along with a team of neighbors, to find out what was truly happening.

As parents, we know surprisingly little about what happens during a school day. We have to trust the school district’s transparency, which was lacking in mine—and many others. Concerned parents asked our District many questions, but we couldn’t get clear answers on anything: how apps were evaluated, how much screen time students were getting, or whether there were documented benefits to this surge in device use. There was no transparency, and no method to ensure that the tidal wave of devices and screen time were actually producing positive outcomes. Nor was there any desire to pause or wait for more data, despite the potential costs to our children. As one school board member put it, “Your children are the guinea pigs.”

The fundamental problem with the implementation of screens in schools today is that it’s been adopted wholesale, haphazardly, and without the consideration of sound research. Schools tout having tablets as “innovative,” regardless of how they’re actually used. Devices that often require little skill to operate can be tremendously distracting, yet their presence is often sold as progress.

The reality is that we need to strike a balance. We should invest in technology that provides students with unique, high-level skills, while limiting tech that produces questionable outcomes, impairs human connection, and exposes students to unnecessary screen time. At Everyschool, we focus on identifying and eliminating problematic EdTech, but we also support incorporating transformative technology when developmentally appropriate into education.

Jon Haidt speaks of the “great rewiring of childhood” that took place from 2010 to 2015. A lot of that re-wiring happened in the classroom. For those who don’t have school-aged children, it can be difficult to grasp how fast this transformation has occurred. The problem is so pervasive and multifaceted that it feels less like a specific issue to address and more like a kind of toxic air we all breathe—parents, students, and educators alike.

What are “Screens in Schools?”

"Screens in schools" refers to all device-based usage in educational settings, whether for learning or recreation. This includes two distinct yet often overlapping areas: Educational Technology (EdTech) and recreational screen time.

EdTech encompasses interactive devices, software, or hardware intended to support student learning. Examples include points-based learning games, YouTube videos, Google Classroom, E-Readers, web browsers, and digital worksheets. Generally, when people talk about EdTech, they focus on technology used directly by students, not administrative tools like filters, surveillance software, or digital grade books.

The other area of concern is the surprising amount of recreational screen time allowed in schools on both school-issued devices and personal cell phones. This includes device use between classes, during lunch or recess, as a reward, after completing work, or whenever there’s unstructured time during the day. It also includes student cell phone use during class, which is usually not allowed but is distressingly common.

While these two categories—EdTech and recreational technology—may seem mutually exclusive, they often overlap. For instance, students may use educational apps during downtime, access recreational YouTube videos on school networks, or bypass parental controls on personal devices by using school-issued devices.

Technology has always been a part of education (a pencil is technology) and computer-based learning has been around for decades (think Math Blaster or Oregon Trail). But since the early 21st century, and especially by the 2010s, the rapid adoption of digital devices has fundamentally changed education. Today, digital devices are integrated into nearly every aspect of school life.

The Anatomy of the Problem

Technology will continue to be a part of everyday life years from now, and our students need to be comfortable and skilled with its use. Failing to teach our students the transformative aspects of modern digital technology would be negligent. The real question isn’t whether screens belong in schools—it’s about how to incorporate them in ways that teach unique skills or elevate learning while protecting students from negative outcomes. That’s where we’ve gone profoundly off track.

Many school districts have adopted devices without a clear plan. One teacher shared that when her district introduced iPads, the only instruction she received was, “Use the device as much as possible.” That’s not the message teachers receive when they get a new set of math manipulatives, paints, or graphing paper. The directive should be to use technology only when it enhances a lesson in ways traditional methods cannot. How much sense would it make if teachers were told to use paint in every single lesson? Sometimes, maybe even most times, paint is simply not required.

This lack of a driving philosophy results in specious practices. Teachers are pressured to use devices and apps because districts have invested millions in technology. Without a sound philosophy and clear guidance, we see problematic EdTech use. For example, students using reading apps like Epic! can swipe through entire books in seconds to earn digital rewards, without actually reading. One parent told me her second grader “read” 40 books during 30 minutes of silent reading. The teacher’s goal was to use the iPad and practice reading. The child’s goal was to collect badges and unlock a new avatar in the app. What we ended up with is a child who had 30 minutes of pointless screen time and no reading practice.

The problem is that screens have saturated every corner of education, often without any clear limits. Why not use a math app? Why not also use the reading app? No reason to stop kids from reaching for their iPad during downtime. A YouTube video can teach third graders Spanish vocabulary, so why not use that? And why fight teens scrolling TikTok during lunch and in between classes? The device is there, but the plan for its use is not—and the magnetic pull of technology is constant. This leads to students spending much of their school day, and even more time outside of school, on devices.

Even if, someday, EdTech could surpass traditional teaching methods (and we’re not there yet), is this screen oversaturation what we want for our children?

Screens in schools haven’t proven to be more effective than traditional methods. Instead, they may be contributing to academic and social-emotional challenges, while displacing the human connection students need most. The topic of screens and schools is complex and nuanced, so we have to look at each layer of the problem to gain insight into best practices. To begin to understand the potential costs of screens in schools, we must acknowledge five big myths that have led us to the misguided place we are today. The simplest place to start is the first layer of the problem: effectiveness.

Myth #1: EdTech Is, On Average, Making Kids Smarter

Many educators have been led to believe that personalized learning apps, algorithms, and educational games yield better outcomes than traditional teaching methods. It’s easy to assume that technology, with its sophistication and innovation, would naturally enhance education.

However, there’s a notable lack of independent, non-industry-funded data showing that EdTech is more effective than traditional methods. While this doesn’t mean EdTech is never or could never be effective, the potential costs—both financial and to children’s well-being—should make us proceed with caution. In fact, there is ample data to suggest that we should pause and reconsider current EdTech practices.

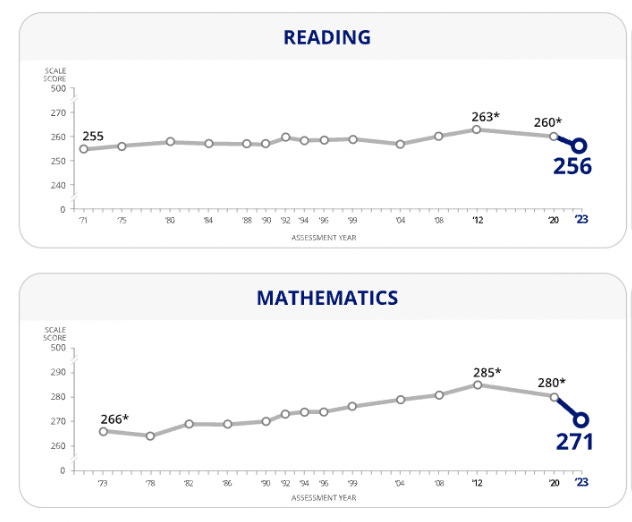

Academic outcomes, from standardized tests to IQ scores, show that students aren’t getting smarter. How much technology has to do with these declines is still debated, but it is certainly a part of the picture. Shortly after the wide-spread adoption of school-issued devices, we began to see an alarming downturn in academic outcomes on the Nation’s Report Card beginning in 2012 that has only continued to worsen. While the pandemic is often blamed for the most recent declines, PISA data indicates “performance was already deteriorating before the pandemic” suggesting “other structural reasons for the decline.”

Global PISA Test Scores in Decline

Figure 1. Declines in math, reading, and science scores averaged across the 38 OECD countries. Image source: The Atlantic, from the OECD.

Declines in Math and Reading Since 2012

Figure 2. Declines in math and reading among American 13-year-olds. Note that the decline did not begin with COVID; it began after 2012. Source: Nations Report Card.

International data shows that countries with more digital technology use in classrooms tend to perform worse on PISA, when controlling for GDP per capita and past test scores. In fact, the OECD found that incorporating technology into the classroom has not shown any appreciable improvements in reading, math, or science outcomes. PISA data essentially echoes the OECD, except for finding some benefits in math outcomes when utilizing technology in moderation. Interestingly, after controlling for socio-economics, the benefit we see from utilizing technology to support math outcomes (14-point gain) is almost equal to the decrease in test scores found when students are distracted by their devices (15-point loss). They note that distraction can come from merely having a device open to take notes. Even when there are potential gains from screens in schools, there is often a loss that comes hand-in-hand.

Despite EdTech companies’ promises, the effectiveness of their products is questionable. Most of the research backing these products is industry-funded with inflated data, and when compared to independent studies, industry data shows inflated gains—up to 70% higher. After independent studies found Pearson products to have no impact, they began funding their own studies—a perfect example of the inordinate influence tech companies have in education. Moreover, when EdTech products are changing, on average, every 36 months, few products remain relevant long enough for us to properly evaluate their effectiveness. Meanwhile, institutions like the American Academy of Pediatrics and the National PTA, which offer guidance on best practices, receive funding from tech companies, raising concerns about bias.

There is enough evidence to make us question the effectiveness of screens in schools, and conversely, there is also convincing data in favor of traditional methods- specifically print reading and handwritten notes. As e-readers replace print, the number of children reading for fun has plummeted, likely because students are three times less likely to enjoy reading if they only read on-screen. Reading in print has the unique benefits of improved comprehension, recall, long-term memory, attention, working memory, and a deeper knowledge of the material. Likewise, handwriting notes improves memory, recall, and conceptual understanding of complicated material, while supporting brain development in young learners. Neglecting handwriting can hinder fine motor skills and areas of the brain used for reading.

Though we can’t definitively say that screens in schools are the sole cause of academic problems, it appears that the rise of EdTech has not led to better overall outcomes. In fact, during the same period, academic performance has worsened. While correlation isn’t causation, it’s hard to argue that the current implementation of EdTech is making kids smarter.

Myth #2: The Delivery Method Doesn’t Matter

The rapid adoption of digital technology in schools sends the message that using screens for educational purposes is harmless. It suggests that EdTech is “neutral,” with no more risk than traditional tools like pencils or paper. However, even if screen-based education was as effective as traditional methods academically, there are still significant losses in using screens as the primary delivery method.

One common form of EdTech is educational gaming, which may seem like a fun way to teach repetitive skills, such as math. But these games are often designed by for-profit companies whose primary goal is to maximize revenue through ad sales and upselling, not learning. Take Prodigy, a popular math game: it takes a staggering 888 questions for a student to show a 1-point improvement on a standardized test. Meanwhile, students are inundated with ads for paid upgrades, creating inequity between students whose parents can afford premium memberships and those who cannot. Imagine a classroom teacher assigning 888 math problems while handing out the best prizes only to students with paid memberships—it’s problematic, to say the least.

Beyond academic effectiveness, educational games trigger dopamine responses, making it harder for students to focus on less stimulating activities later on. This compulsion loop pulls students toward screens for entertainment rather than engaging in more developmentally appropriate activities, such as playing with friends, reading a book, or practicing creativity. We often focus on whether an educational game “works” academically, but we ignore the compounding negative effect it may have on student focus and well-being.

Here are examples from real students that illustrate how the delivery method matters, and why devices aren’t neutral in the classroom:

A fourth grader using E-Readers for all assigned reading retains less information and performs worse on tests than previous classes who read print books.

A fifth grader with a substitute teacher spends music class watching Fortnite shorts on YouTube instead of engaging in healthier activities like reading or playing a board game.

A third grader is exposed to pornography when a classmate sends inappropriate photos on a school-issued tablet while on a WiFi-enabled school bus.

A kindergarten teacher reviews class Facebook page "likes" on a smartboard, teaching students that external validation is more important than the intrinsic rewards of learning.

A student who learned her letters finger-writing on an iPad struggles with handwriting, reducing her conceptual understanding and test performance because she relies on typing.

Students opening YouTube accounts with school-issued email addresses, without parental consent, gaining access to inappropriate content.

A seventh grader completes orientation through QR code scans and videos, missing opportunities to connect with peers during a crucial social time.

A tenth grader struggles with focus due to constant distractions on her laptop and phone, leaving her sleep-deprived, irritable, and underperforming academically.

The 41% of teens who access pornography during the school day, nearly half of which do so using school-issued devices. No amount of diligence by school staff or internet filters can 100% prevent children from seeing inappropriate content, disinformation, and developmentally inappropriate material.

The delivery method does matter. Simply using a device in an educational setting doesn’t negate its downsides. Devices bring with them a host of distractions, developmental concerns, and social-emotional issues that can’t be ignored, even in the context of learning.

Myth #3: EdTech is Necessary to Teach 21st Century Skills

Tech companies often push the idea that students need tech skills to succeed in the 21st century. Technology is fast-paced, exciting, and can, at times, require complex skills to navigate. We fear our children will be left behind if they are not on devices from a young age and preparing for jobs of the future.

The reality is, the skills students are more likely to miss are soft skills—critical thinking, collaboration, communication, problem-solving, interpersonal skills, creativity, and even simple eye-contact. These are the skills they’ll need to navigate the ever-changing landscape of technology and future workplaces.

Let’s look at three crucial 21st-century soft skills that screens in schools may actually be undermining: attention, self-control, and creativity.

Attention: Current classroom practices with devices often teach distraction more than focus. Students might play overstimulating educational games, rush through assignments to get to recreational screen time, or read online articles instead of reading full-length books. Many EdTech platforms constantly compete for students’ attention, making deep, sustained focus harder to achieve.

Childhood and adolescence are not just irrelevant towns we pass through on the way to adulthood; they are profoundly critical stages for brain development. When students are frequently encouraged to fill downtime with screen use, their brains form automatic habits around device use, making it harder for them to focus on more demanding tasks, or on almost anything in the real world, because the real world is rarely as stimulating as a screen. Adolescents, whose prefrontal cortex (responsible for judgment and impulse control) is still developing, are particularly vulnerable to distractions. Instead of learning to focus, they’re developing the habit of escaping from difficult tasks in favor of mindless digital activities.

Self-control: Self-control is linked to success in life, but it’s not something adolescents can develop on their own. Their executive functioning is still maturing, so adults need to help them build self-control and self-regulation skills.

The saturation of devices in school is hindering the development of self-control and setting many students up for failure. PISA 2022 data shows that a quarter of students reported feeling distracted by the devices that other students were using in most or every class, and indicated that devices negatively affected the flow of class. Even back in 2013, one study found that students couldn’t make it 6 minutes before getting distracted by the many enticements their laptop has to offer. Imagine how much harder that is in 2024. If limits on laptops are trending at Harvard, perhaps we need to consider this for our K-12 learners as well.

Creativity: While technology can enhance creativity, it can also limit it. Creativity—defined as the “production of something original and useful”—requires “divergent thinking (generating many unique ideas) and then convergent thinking (combining those ideas into the best result).” Creativity scores were rising for decades but began to decline in the 1990s, coinciding with the rise of technology replacing free play. The decline has been most pronounced in younger students.

Fostering creativity requires openness to unconventional answers and a willingness to follow curiosity—things that pre-programmed educational tech often stifles. When technology sets the parameters, students may lose the ability to think outside the box or take intellectual risks. Creativity researcher Dr. Kyung Hee Kim advises that creativity is nurtured by promoting play, encouraging open-ended assignments, and fostering intrinsic motivation—factors that are often displaced by the nature of EdTech.

A child starting school this year will retire around 2084. With the rate at which technology is evolving, how on earth can we know what digital tools students will be using during their careers? We can’t. But we do know if they are strong in their soft skills, they will pivot, be creative, problem-solve, and figure it out.

Myth #4: Kids (These Days) Need Fun and Engaging Devices To Learn

There’s no doubt that kids are drawn to screens like a moth to a flame. The lure is even stronger when it’s a personal device that they control. Many teachers, with their earnest desire to create joyful, engaging classrooms, may see devices as tools to keep students interested. But there’s a critical difference between genuine engagement in learning and attention hijacking. Students may appear focused on their screens, but often, it's merely the device (not the material) that has captured their attention.

Waldorf education drives this point home beautifully. Waldorf schools, which avoid all screens until at least the seventh grade and emphasize real-world skills, show classrooms full of engaged, happy students. These students spend time in nature, working with their hands, and interacting with peers—without screens and devices. While this approach may not be for every family, it starkly contrasts with many traditional schools, where students are rewarded with digital prizes and teachers feel pressured to incorporate devices into lessons to maintain engagement. Waldorf schools are heavily used in Silicon Valley by the parents who work in the tech industry, yet actively limit technology in their own children’s education.

The constant presence of overstimulating devices and tools creates a never-ending competition to find something even more exciting to grab students’ attention. But for kids today, devices are hardly novel—the average teenager spends nearly nine hours a day on recreational screen time alone. With the best of intentions, we try to grab student attention through exciting means, but this sets the bar of entertainment in education at a place that is unsustainable when learning gets hard and requires self-governed focus and attention.

Myth #5: Technology is Connecting

In a world where everyone is just a text, Snap, or call away, it seems like human connection should be richer than ever. We can tweet at authors, share our work online, and hear from experts on YouTube. But does this digital interaction really make us feel more connected?

The reality is that technology is an impoverished substitute for in-person relationships. Despite endless ways to communicate digitally, our students are lonelier and more depressed than ever—nearly 3 in 5 teen girls report persistent sadness, and loneliness has doubled in the past decade. Loneliness matters: having a best friend at school is the best predictor of engagement. What combats loneliness? Human presence, eye contact, and feeling heard. Yet, in today’s schools, students are glued to devices in class and on their phones during downtime, leaving little room for genuine connection.

This disconnecting effect of technology is illustrated in a finding from Jean Twenge, Jon Haidt, and their colleagues. They found that in the PISA dataset, there were 6 questions on loneliness at school. As you can see in the figure below, loneliness self-reports were stable until the 2012 data collection. But over the next few years, when iPads and Chromebooks began pouring into classrooms around the world, loneliness increased, around the world.

Rising School Alienation Since 2012

Figure 3. Changes in school alienation, 2000-2018 (teens ages 15-16), n = 1,049,784. Source: Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), 2002-2018. No data 2006 and 2009.1

Human connection has a foundational significance in a teaching relationship. The “best” teachers aren’t great because of their tech tools; they’re great because students feel they care. That bond doesn’t exist with a computer-based learning program. UNESCO notes that more than 25 million students have used a particular AI learning and assessment system, despite research showing it is not more effective than traditional methods. Digital programs lacking data-backed benefits merely swap face-to-face time with screen time, and jeopardize human connection.

In The Anxious Generation, Jon Haidt refers to “experience blockers” and this concept applies to screens in schools as well. When devices dominate education, they displace essential activities that foster social-emotional growth. Instead of collaborating face-to-face, students often work silently and separately on their own devices. Instead of lively lunchtime conversations, they stare at screens. These moments of interaction are critical for learning life’s important lessons. As devices take over, we lose these little moments, eroding school culture and, more importantly, the connections that make us healthy and happy.

What Schools Can Do

Our schools need to adopt a purposeful, intentional, research-based approach to technology. Instead of trying to make screens the solution to our educational problems, we must evaluate tech use with a critical, unbiased lens while considering academic outcomes, mental health, and digital wellness.

To help guide schools, Blythe and I developed EdTech’s 10 Best Practices and The EdTech Triangle, which simplify research from education, child development, and mental health. The EdTech Triangle helps schools prioritize technology that is transformative or supportive in the educational environment, while reducing or eliminating tech that restricts learning or breeds habitual use.

Additionally, we created the R.E.A.C.H. model to guide schools toward digital wellness. Here’s how it works:

R: Remove Weak Tech – Limit or eliminate tech that disrupts learning or restricts outcomes. For younger learners, prioritize play, movement, and hands-on learning over screens. Avoid using tech as a "brain break" or reward, as screens overstimulate rather than refresh. Encourage print materials for reading and note-taking, and reduce digital homework to minimize distractions and improve sleep. Eliminate the use of social media as a communication tool between the school and students, including school-sponsored athletic teams and other afterschool activities.

There are no research-based reasons an educator should feel compelled to use devices, but there are many potential harms, especially for our youngest learners (K-5th). Until a body of clear non-industry-sponsored research studies say otherwise, eliminating personal school-issued devices completely in elementary school would be ideal. Instead, a computer lab or computer cart would be an effective way to introduce foundational tech skills (i.e.: typing) as students near middle school, without giving them a device that fosters distraction and inattention.

E: Embrace Powerful Tech – Use tech that supports learning in unique ways and teaches high-level skills. Examples of this include robotics, website design, digital marketing, or music editing. Implement multi-year digital citizenship courses and a comprehensive typing curriculum. When students are developmentally ready, incorporating certain skills such as spreadsheet creation, locating online resources, data privacy, online etiquette, citing sources, and design software are tools almost all graduates would benefit from understanding, no matter their career goals. Focus on integrating tech only where it adds value, not where traditional methods work just as well or better.

A: Accept the Digital Dilemma – Acknowledge that excessive tech use is linked to negative outcomes like poor focus, sleep problems, and anxiety. We have to actively teach students how to minimize the pull of devices and help them develop focus by limiting distractions.

Educators are revered as the experts on children, giving schools the unique power to alter the norm by sharing research and data with parents, providing speakers to the school community, and setting the tone for healthy tech use in schools. Providing the space and encouraging parents to come together to build community and support each other in home-based screen time struggles both strengthens parents and helps shift the culture. Everyschool offers a free curriculum to do so on our website.

C: Create a Tech Plan – Schools should have a clear, written technology plan outlining their philosophy and policies on tech use, including cell phones. The EdTech Triangle offers a simple framework for communicating tech priorities to staff and parents. Thoughtfully evaluate apps, licenses, software, and devices currently in use and determine which ones align with healthy tech use and are actually being utilized by staff and students. Schools should also ensure accountability and update their tech plan as new data becomes available.

Have a balanced teacher education plan. Know that if a representative of a for-profit tech company is providing education to your teachers, it is unlikely they will be presenting their product, or its effectiveness, with an unbiased lens. As important as it is for teachers to stay abreast of trends in technology, it’s equally important to balance teacher professional development with experts in child development, mental health, and non-tech methods of teaching.

H: Honor Human Connection – Human relationships are key to academic success, engagement, and well-being. If technology displaces face-to-face interaction, it’s doing more harm than good. While the device itself can be problematic, what’s even more concerning is all the opportunities lost to develop deep bonds with others, giving and receiving empathy, and developing a sense of belonging to a community that surpasses self-interest.

The most effective place to start to improve academic outcomes, reduce educational inequalities, and improve well-being is to deal with recreational tech use first by making your school a Phone-Free School. This can improve social-emotional well-being and help students develop deeper bonds with peers and teachers. If you would like to encourage your own district to go phone-free, visit www.phonefreeschools.org, a campaign powered by Everyschool.

It may feel like the genie is out of the bottle, and now we need to live with the disappointing results of a tech-heavy education. However, with intentional steps and purposeful changes, schools can move toward a digitally-well environment that supports the developmental stages of their students, their emotional health, and bolsters academic outcomes. Our students have been guinea pigs long enough, and we have enough data to show us there is a better way. It is time to bring digital wellness to every school for every student.

Items include: “I feel like an outsider (or left out of things) at school,” “I make friends easily at school” (reverse-scored), “I feel like I belong at school” (reverse-scored), “I feel awkward and out of place in my school,” “Other students seem to like me” (reverse-scored), and “I feel lonely at school.” Response choices range from strongly disagree to strongly agree (1-4).

We have falsely equated tech in schools with progress. Yet it is the children who are able to dive into books for an extended period of time, put pen to paper to capture their thoughts, and keep eye contact while conversing with others that will be the ones who set themselves apart from a distracted generation.

Excellent summary of why we need to dispell the myth of "tech equals progress" and change course in our educational system. Thanks for your work!

Thank you for addressing this. In my opinion there is no need for any personal screen access for K-3 (at least). My daughter is in first grade and this year her teacher has them reading on iPads. I have yet to see one actual book come home. This is unacceptable!

I’m an older millennial who didn’t have any computer skills until college and guess what, I know how to work apps. Especially since the best apps are designed to be intuitive. Why are kids reading on iPads. Infuriating