Applying The Bradford Hill Criteria To Social Media Use and Adolescent Mental Health

Anna Lembke discusses how the nine criteria used to demonstrate causality in the Surgeon General's 1964 advisory on smoking can improve our thinking about the effects of social media

Introduction from Jon Haidt and Zach Rausch:

Anna Lembke’s book Dopamine Nation is the book to read to understand how and why digital activities can become addictive. Lembke is a psychiatrist and professor at the Stanford University School of Medicine, where she is the chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic. We drew on Dopamine Nation in writing the behavioral addiction section of chapter 5 of The Anxious Generation, where we quoted her memorable line: “The smartphone is the modern-day hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation.”

So when Jon saw her name listed as a guest on Peter Attia’s excellent podcast, he tuned in and learned a lot. They discuss the nature of addiction, the role of dopamine, and behavioral addictions such as gambling. At 1:08 in the podcast, they discuss sexual addictions and the effects of pornography on a boy's developing brain. Then, at 1:43, they turn to social media.

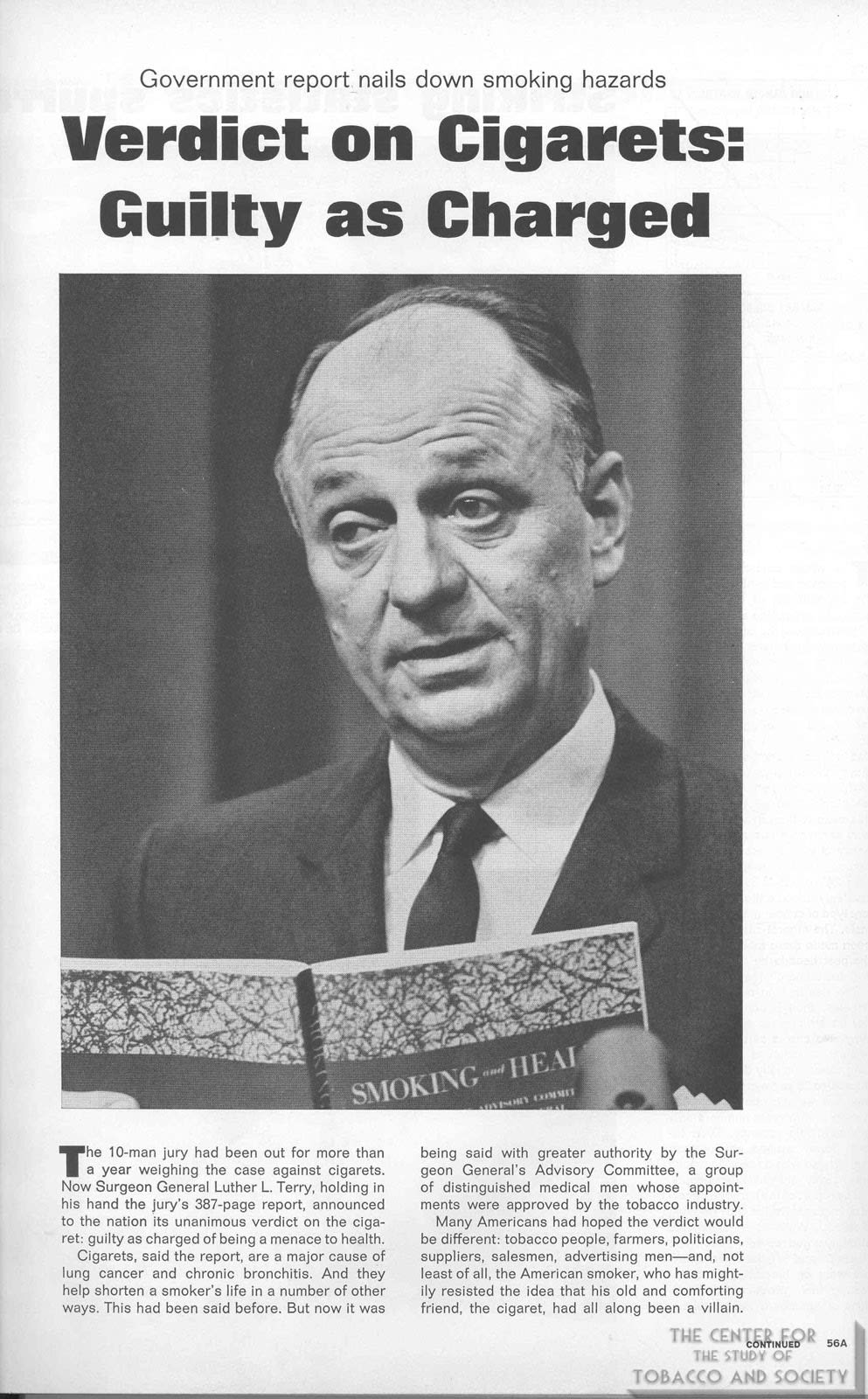

Attia brings up The Anxious Generation and notes that there is extensive debate over whether (and to what extent) heavy social media use is merely correlated with anxiety and depression, or whether there is evidence that social media use causes these bad mental health outcomes. He notes that there was a similar debate about tobacco in the 1950s and 1960s, a debate that was not resolved by experiments with control groups (since it would be unethical to randomly assign one group of subjects to smoke for a few decades while a control group went without cigarettes). Rather, Attia mentions the “Bradford Hill criteria” that were used within the scientific community to address when one factor (such as cigarette smoking) can be said to have caused a health outcome (such as lung cancer), and he asks Lembke to give her thoughts.

When Jon heard Lembke working through these criteria in regard to social media, he immediately thought that this would be of interest to readers at After Babel. We invited Lembke to turn that section of the podcast into a post, and we are grateful to her for putting in the time to do so. In the post below, Lembke will detail each of the nine factors of the Bradford Hill criteria, illustrating how this framework can be applied to questions about the effects of social media on adolescent mental health. Throughout the post, examples from Zach will help clarify how this method can guide us toward answers to key questions about causality in regard to social media.

To be clear, we are not using this post to claim that a causal relationship has been definitively established. This would involve a lot more work, since, for example, all relevant studies and available data need to be considered to properly evaluate the Bradford Hill criteria. Rather, we aim to introduce a powerful method that researchers can use to approach questions of causality more systematically. One of the central issues in current debates is that there is no consensus on which criteria must be met to conclude that a causal effect exists. We hope this discussion will move us closer to common ground.

Finally, it’s important to recognize that establishing causality does not require every individual to be affected in the same way. The vast majority (close to 90%) of lifelong smokers never develop lung cancer, and not all adolescents who use social media heavily will experience harm, not to mention develop clinical depression. Individual differences matter, and some groups are more vulnerable than others. Certain behaviors can also offer benefits even if they come with significant risks. The bottom line is that it is often hard to establish causality, but we can look back to previous public health challenges to help us think more clearly about this one.

– Jon and Zach

Applying The Bradford Hill Criteria To Social Media Use and Adolescent Mental Health

By Anna Lembke

Multiple large databases have shown a correlation between social media use and poor mental health outcomes in teens. Namely, teens who are heavy users of social media are more likely to suffer from depression, eating disorders, body dysmorphia, and other mental health harms. The link is often larger for girls.

The core question is whether (and to what extent does) A) heavy social media use causes poor mental health in teens, B) poor mental health causes teens to use more social media, C) some combination thereof, or D) some third variable (such as, say, parental neglect) causes students both to use social media more and to have worse mental health, creating what appears to be a correlation but yet would not mean that social media caused mental health problems. In this essay, I show how the Bradford Hill Criteria can be used to answer these questions. The criteria provide a useful paradigm for examining the question of causality, especially in instances when there is a delay between exposure to a risk factor and occurrence of a disease, and when other causal factors might play a role. The classic example is smoking cigarettes (risk factor) and much later on, developing lung cancer (disease).

For much of the 20th century, the scientific literature reported an “association” (correlation) between exposure to cigarettes and the occurrence of lung cancer, that is, lung cancer was found to have occurred more frequently among smokers. However, cigarette manufacturers denied their products “caused” the increased number of lung cancer cases and attributed the association instead to other factors––third variables like innate propensity for cancer and exposure to other environmental toxins, such as asbestos and air pollution.

In 1956, the noted British epidemiologists Sir Austin Bradford Hill and Sir Richard Doll published an influential study of smoking and lung cancer among physicians in Britain. This article rejected alternative explanations for the increase in lung cancer, e.g., the claim “that smoking does not produce cancer in a person in whom cancer would not otherwise have occurred at all, but merely determines the primary site of a growth that is destined to appear in some part of the body,” and that “atmospheric pollution” might explain the increased risk.Hill and Doll observed a higher mortality rate in smokers than in non-smokers, a higher mortality rate in heavy smokers than in light smokers, and a higher mortality rate in those who continued to smoke than in those who gave it up. In 1964, their study became part of the data set that resulted in the 1964 Report of the United States Surgeon General that “cigarette smoking is causally related to lung cancer in men; the magnitude of the effect of cigarette smoking far outweighs other factors. The data for women, though less extensive, point in the same direction.”

In 1965, one of the authors of that landmark smoking study, Sir Austin Bradford Hill, published an essay that has become the framework for answering the question of when a statistical finding of association meets threshold criteria for causation: “What aspects of that association should we especially consider before deciding that the most likely interpretation of it is causation?”

The “Bradford Hill factors,” as they have become known, are generally accepted in the scientific literature as a leading methodology to determine whether there is a causal relationship between exposure to a risk factor and the occurrence of a disease, particularly when working with empirical data and when randomized controlled trials are difficult if not impossible to conduct.

The nine factors cited by Bradford Hill to determine whether an association is causal are as follows: (1) Strength of the association, (2) Consistency, (3) Specificity (4) Temporality, (5) Dose-response relationship, sometimes called “biological gradient,” (6) Plausibility, (7) Coherence, (8) Experiment, and (9) Analogy.

These factors are a guide, not a checklist. As a reference manual on scientific inference explains:

There is no formula or algorithm that can be used to assess whether a causal inference is appropriate based on these guidelines. One or more factors may be absent even when a true causal relationship exists. Similarly, the existence of some factors does not ensure that a causal relationship exists. Drawing causal inferences after finding an association and considering these factors requires judgment and searching analysis, based on biology, of why a factor or factors may be absent despite a causal relationship, and vice versa. Although the drawing of causal inferences is informed by scientific expertise, it is not a determination that is made by using an objective or algorithmic methodology. These guidelines reflect criteria proposed by the U.S. Surgeon General in 1964 in assessing the relationship between smoking and lung cancer and expanded upon by Sir Austin Bradford Hill in 1965 and are often referred to as the Hill criteria or Hill factors. (Italics added for emphasis.)

I provide here a brief primer on how the Hill criteria might be applied to social media exposure and mental health disorders in teens. This is neither an exhaustive review of the criteria nor a complete analysis of any one criterion.

Important to this analysis is study stratification based on the amount of social media being used in a given study population. Unlike cigarettes, in which no amount of tobacco consumption is healthy, a small amount of social media consumption may be neutral or even beneficial, whereas excessive use is likely to be harmful, analogous to the application of the Hill criteria to alcohol and sugar beverage consumption. It has also been applied to gambling.

For example, alcohol research has shown that the healthiest people drink no more than one to two standard drinks a day, and above that amount, all-cause morbidity and mortality increases. People in this category are also healthier than non-drinkers, not because drinking has any specific salutary effects, but rather because non-drinkers include the sub-group of ‘sick-quitters’ – people who had to stop drinking due to severe illness, often alcohol related. A secondary modifying factor is that people who drink in moderation also do other things in moderation, like eating and exercise. More recent data shows that no amount of alcohol consumption is healthy in young people.

Criteria 1. Strength of the Association

In epidemiology, the strength of association between exposure and harm is typically measured as relative risk (RR), such as the finding that smokers have a roughly 70% higher annual mortality compared to non-smokers. There are various ways to measure exposure and harm (such as annual versus lifetime), but as long as there is a reliable and relevant RR result, it may be considered for the Bradford Hill 'Strength of Association' criteria.

For cigarette smoking, for example, the risk of lung cancer in smokers is approximately 10 times the risk in nonsmokers. For heavy drinkers (> 7 drinks/week for women and > 14 drinks/week for men), the risk of death from all causes is 1.15 times the risk in non-drinkers, showing an increased relative risk, but not of the same strength as smoking and lung cancer. A smaller strength of association does not mean there is no effect, but in general, a larger association can be evidence that it is more plausible that a causal relationship exists..

In the case of social media, the relative risk of mental health harms will be impacted by other factors such as pre-existing psychiatric conditions, adverse social determinants of health (poverty, trauma, discrimination, etc), and gender. Hence, application of the Bradford Hill criterion needs to account for subpopulations of teens who may be more vulnerable. The strength of association between social media exposure and mental health harms may be weak for the general population but stronger in vulnerable groups. In my clinical experience, teens with co-occurring psychiatric disorders are more likely to get addicted to and be harmed by social media than teens without, and girls are more vulnerable than boys.

Illustrative Example from Zach:

Using the UK Millennium Cohort of 10,904 UK 14-year-olds, Kelly and colleagues (2018) found that the risk of depression in girls who are heavy social media users (spend > 5 hours a day) is 3 times higher than in girls who do not use social media at all. For males, the risk of depression is 2 times larger for heavy users compared to non-users.

Criteria 2: Consistency

Consistency refers to whether similar findings have been “repeatedly observed by different persons, in different places, circumstances and times.”

In the case of alcohol, much of the discourse in the early 20th century was about the beneficial health effects of alcohol. But with more research over the intervening decades, the literature now indisputably shows “the harmful effects of alcohol on different body systems.”

The scientific literature on the mental health impact of social media is still in its infancy, but as more studies emerge, I suspect that, as with alcohol, there will be mounting evidence that heavy social media consumption, especially by vulnerable populations, contributes to mental health harms.

Illustrative Example from Zach:

In Amy Orben’s 2020 narrative review of reviews and key studies, she finds that the associations between social media use and depression range between .10 to .15 across a variety of meta-analyses. One of those meta-analyses, Hancock and colleagues (2022), examining 226 studies from 2006 through 2018, found a significant relationship between social media use and anxiety (r = .13, p < .01, 95% CI [.04, .22]) and depression (r = .12, p < .01, 95% CI [.07, .17]) and that “relationships between social media and all forms of psychological distress were not different between participant regions.” (Regions included North America, Asia, Middle East, Australasia, Europe, and others).

[Note that both Orben 2020 and Hancock 2022 do not split results by sex, blending together boys and girls. The associations with depression are generally larger for girls]

Criteria 3: Specificity

Specificity has to do with the absence of any other likely explanation for the rise in disease incidence. Indeed a common defense of environmental toxins by their commercial manufacturers is ‘other aspects of modern life.’ The tobacco industry defended cigarettes in part with “... statistics purporting to link cigarette smoking with the disease could apply with equal force to any one of many other aspects of modern life.”

Naysayers of social media harms have often pointed to other aspects of ‘modern life’ that can contribute to our youth mental health crisis, such as social dislocation, trauma, discrimination, and so on. But just because other factors play a role, that doesn’t detract from the impact of heavy social media use on poor mental health.

Given the complex etiology of mental illness, specificity may not be fully achievable for this analysis; but keep in mind that “One or more factors may be absent even when a true causal relationship exists.”

Illustrative Example from Zach:

In one After Babel post, Psychologist Jean Twenge walks through thirteen alternative explanations for why teen mental health has worsened over the last decade and shows why these explanations are not sufficient to explain the vast majority of the rise.

Criteria 4: Temporality

According to Bradford Hill, “A temporal, or chronological, relationship must exist for causation to exist. If an exposure causes disease, the exposure must occur before the disease develops. If the exposure occurs after the disease develops, it cannot have caused the disease.”

Proving a temporal relationship for mental illness can be difficult because mental illness tends to have a slow onset and a relapsing and remitting course, making it difficult to identify a specific time point when the mental illness began. Further, mental illness may be a risk factor for exposure to the environmental toxin, as well as being caused by the environmental toxin, in a feed-forward cycle that is causally true in both directions. For example, people struggling with psychiatric disorders are more likely to use drugs and alcohol, and drugs and alcohol can cause or exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. Early onset cannabis use has been correlated with later development of psychosis and worsened schizophrenic symptoms in patients followed over decades.

Therefore, naturalistic studies which examine rates of disease in large populations before and after exposure to a toxin, and cohort studies which follow a population over long periods of time, are powerful tools for examining temporality in the setting of mental health harms.

Illustrative Example from Zach:

Looking at 990 non-depressed young adults (ages 18-30), Primack and colleagues (2021) followed these young adults for six months and found that their “baseline social media use was strongly and independently associated with the development of depression during the subsequent 6 months.” They also add that there was no association between the presence of depression at baseline and an increase in social media use over the course of the study. Similarly, a new 2024 meta-analysis by Ahmed et al. (2024) found that “Baseline SMU was associated with later depression, but not vice versa.”

Criteria 5: Dose-response relationship, sometimes called “biological gradient”

Of the dose-response relationship, the Bradford Hill paper states:

[I]f the association is one which can reveal a biological gradient, or dose-response curve, then we should look most carefully for such evidence. For instance, the fact that the death rate from cancer of the lung rises linearly with the number of cigarettes smoked daily, adds a very great deal to the simpler evidence that cigarette smokers have a higher death rate than non-smokers.

The literature for cigarettes, alcohol, and sugar all show a compelling biological gradient: The more of the substance ingested, the greater the harms. For social media, evidence for a biological gradient is robust. The more time teens spend using social media, the more likely they are to suffer adverse mental health consequences.

Illustrative Example(s) from Zach:

A meta-analysis by Liu and colleagues (2022) of 27 studies of a total of 55,340 adolescents found a 13% increased risk of depression for every one hour increase of use of social media.

Example figure of the dose-response effect from Kelly et al. (2018):

Percent of UK Teens Depressed as a Function of Hours per Weekday on Social Media

Figure 1. Heavy users of social media are more depressed than light users, in a “dose-response” fashion. (Source: Millennium Cohort Study, analyzed by Zinawala, Kelly et al. 2018 (study mentioned in criteria 1). [Zach’s spreadsheet]

Criteria 6: Plausibility

According to Bradford Hill, “Biological plausibility … depends upon existing knowledge about the mechanisms by which the disease develops. When biological plausibility exists, it lends credence to an inference of causality.”

The organ we’re using when we’re consuming social media is our brains. The organ that is affected in any psychiatric condition is the brain. At its most basic level, it is biologically plausible that heavy use of social media, which provides hours each day of an unusual kind of stimulation, can harm our brains, just as it is biologically plausible that inhaling cigarettes harms our lungs.

One of the mechanisms by which social media might cause mental health harms is through its addictive design features – notifications, algorithms, infinite scroll, and so on – leading us to consume social media beyond what is healthful or even pleasurable. If indeed the harms of social media are mediated in part by compulsive overuse, i.e. addictive use, then it would be important to show that social media acts on the brain’s reward pathway, the part of the brain that is affected by the disease of addiction. Indeed there is such evidence.

The brain’s reward pathway is activated by oxytocin, our love hormone, which binds to dopamine-releasing neurons in the brain’s reward pathway, dopamine being our brain’s reward neurotransmitter, which explains why falling in love feels so good. Beyond this single study, a rich literature in neuroscience supports the finding that making human connections—a definitional feature of social media—is rewarding for the human brain.

Human brain imaging studies demonstrate that tasks that involve “acquiring a good reputation” robustly activate reward-related brain areas and overlap with the areas activated by monetary rewards. The authors conclude, “Our findings support the idea of a ‘common neural currency’ for rewards and represent an important first step toward a neural explanation for complex human social behaviors.”

Meshi and colleagues have shown that reward-related activity in the left nucleus accumbens, a core nucleus of the brain’s reward pathway, predicts Facebook use, strengthening the biological plausibility that Facebook and drugs of reward activate the same reward pathways in the human brain.

To be sure, more studies of social media’s specific impacts on the human brain are needed, but I believe there is sufficient evidence to date to infer that it is biologically plausible that social media use can cause mental health harms.

Illustrative Example from Zach:

Maza and colleagues (2023) followed the social media habits of 169 sixth- and seventh-graders for three years, along with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of their brains. They found that “participants who engaged in habitual checking behaviors showed a distinct neurodevelopmental trajectory within regions of the brain comprising the affective salience, motivational, and cognitive control networks in response to anticipating social rewards and punishments compared with those who engaged in nonhabitual checking behaviors”.

The authors concluded that “habitual checking of social media in early adolescence may be longitudinally associated with changes in neural sensitivity to anticipation of social rewards and punishments, which could have implications for psychological adjustment.”

Criteria 7: Coherence

Bradford Hill’s coherence criterion is one of unification, an attempt to ensure that the various data points supporting causality do not conflict.

The examples Hill gave for coherence included the microscopic effects of smoking on lung cells and the difference in lung cancer incidence by sex. These examples could fit under biological plausibility as well as coherence. The point is that coherent information supports causality and conflicting information is evidence against causality.

For social media, an example of coherence is the idea that addiction to social media is a mechanism of brain harm, and that social media harm occurs in a dose dependent fashion (biological gradient): The more social media consumed, the worse the mental health outcomes.

Illustrative Example from Zach:

Hill used the “association with cigarette smoking coherent with the temporal rise that has taken place in the two variables over the last generation and with the sex difference in mortality” as evidence of coherence. We can point to similar coherence with social media. See Rausch and Haidt (2023) and Haidt (2024) where Jon and I demonstrate the corresponding rise of smartphones with social media platforms (especially Instagram) with the rise of internalizing disorders among adolescents (especially girls) in the early 2010s.

Criteria 8: Experiment

Bradford Hill explains, “Occasionally it is possible to appeal to experimental, or semi-experimental, evidence. For example, because of an observed association some preventive action is taken. Does it in fact prevent? The dust in the workshop is reduced, lubricating oils are changed, persons stop smoking cigarettes. Is the frequency of the associated events affected? Here the strongest support for the causation hypothesis may be revealed.” Hill AB, The Environment and Disease, fn. 105, above, at 298-299 (emphasis added).

In clinical care, we frequently observe significant improvement in mental health outcomes when patients abstain from digital media, including social media, for a period of time. We always warn patients that they will likely feel worse before they feel better, as immediate cessation is often accompanied by withdrawal. The universal symptoms of withdrawal from any addictive substance or behavior are anxiety, irritability, insomnia, dysphoria, and craving. The first 10-14 days are the worst, and thereafter patients start to feel better. If they can maintain abstinence for at least four weeks, they often feel better than they have in a very long time, without receiving any other treatment. This observation perhaps more than anything else has convinced me that heavy/addictive social media use can cause mental health harms, and likewise cessation or reduction of social media use can improve mental well-being.

Any scientific study looking at outcomes of mental health indicators after stopping social media should take into account the period of withdrawal which will initially make psychiatric symptoms worse. Also, although reduction of use may be beneficial, for more severe psychiatric problems, complete cessation of use for a period of time may be necessary, at least based on my clinical experience.

Illustrative Example from Zach:

Davis and colleagues (2024) randomly assigned 220 students with high emotional distress to lower their social media usage to 60 minutes per day or else to make no changes to their social media use (control group), for three weeks. They found that students who were asked to reduce social media use showed significant decreases in depression, anxiety, and FoMO (fear of missing out), and increases in sleep.

Criteria 9. Analogy

Hill's description of analogy involves contrasting two bodies of evidence, one from an established causal relationship, to infer a causal relationship in the experimental condition.

There is remarkable phenotypic similarity between social media addiction and drug and alcohol addiction, suggesting they are the same disease process.

In the case of drug and alcohol addiction, or even addiction to behaviors like gambling or food, an individual who finds a given drug reinforcing is likely to continue to use that drug repeatedly, especially if it is readily available at low or no cost. The more they use, the more their brain adapts to the rewarding effects of the drug, and the more they need to get the same effect, called tolerance. Eventually they may progress to the point where they’re experiencing the 4 C’s of addiction: 1) Out of control use, 2) compulsive use, 3) cravings, and 4) consequences, especially continued use despite consequences [DSM-5]. They can experience acute withdrawal when they cut back or stop, a predictable physiological reaction that lasts on average 10 to 14 days. At this point, the brain mistakes the drug as necessary for survival and the individual has lost some degree of personal agency, such that they cannot stop using even if they want to.

In clinical care, we see patients who consume social media to the point of not being able to control their use, compulsively using even when they don’t plan to or want to, craving social media when they’re not using, and experiencing significant mental health consequences as a result of overuse. They can experience tolerance, like needing to get more ‘likes’, maintain a certain ranking or social standing on the platform, and/or needing more extreme content to get the same effect. We also observe some patients experiencing physical and mental withdrawal when they try to stop social media. In children, withdrawal from social media often manifests as extreme rage, anxiety, dysphoria, and insomnia, which typically resolves within 10 to 14 days of abstinence.

Illustrative Example from Zach:

Zhao and colleagues (2022) used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, which included structural MRI scans from 10,691 adolescents. They found a pattern of structural features that was associated with heavy “Screen media activity (SMA)”. The authors report that:

“This covariation pattern highly resembled one previously linked to alcohol use initiation prior to adulthood and was consistent in girls and boys. Subsequent regression analyses showed that this co-variation pattern associated with SMA (β = 0.107, P = 0.002) and externalizing psychopathology (β = 0.117, P = 0.002), respectively.”

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Bradford Hill criteria provide a roadmap for exploring causality between heavy social media use and mental health harms, analogous to addictive use of drugs, alcohol, and sugar. As with any new environmental toxin, sentinel case reports and clinical observation will always precede clinical studies. Indeed it is just these early reports and observations that inform the need for causal analyses to follow. As with any addiction, some groups will be more vulnerable than others. In this case we can expect that adolescents, those with co-occurring mental illness, and those facing adverse social determinants of health such as poverty and trauma will be more vulnerable to harm from social media. These vulnerable subpopulations should be considered separate and apart from the general population. The complexity of mental illness means that for any given person, there will likely be multiple causative agents, but the presence of multiple risk factors does not block us from pointing to a probable causal contribution of social media to poor teen mental health.

Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy has issued an advisory report on the harms of social media in children and has recommended in an Op-Ed essay in the New York Times that social media carry a warning label, cautioning consumers about the dangers of social media. I agree.

Brilliant article, and yet here we are again using scientific criteria to establish a link between social media use and mental health, all while simple observation and common sense tell us without any doubt that kids with smart phones are much more likely to be detached from their families, isolated, and prone to depression and other mental health disorders. If we continue this level of insistence on proving the obvious, perhaps we need a study to establish whether infants are more or less healthy when they are fed grass clippings instead of formula.

Before the existence of smartphones and social media, is there any doubt whatever that the single factor most important in establishing the mental health and “success” of children was the physical, emotional, and moral environment created by parents? No, and yet now, since the introduction of phones, we have somehow dismissed this central role of parents?

The simple truth is that minor children living at home—who depend on the care of their parents—do not need phones at all. They’ve lived without them for thousands of years, and the past dozen years have not proven that the net value of phones is positive. Sure, children do sometimes need internet connection—notably for school assignments—but they can do that from a home computer or school computer, where their screens can be seen at all times and their internet history examined. And parents must stop their silly attempts to manage phone use and social media—which kids quickly learn to bypass—and go straight for removing smartphones entirely. Millions of children with sensible parents have proven that the policy of no phones actually works, while all the corporate and parental controls in the world are but feeble obstacles for children to dodge.

But simple phone removal is not enough, just as drug treatment centers have proven that withdrawal without support is useless. We can’t just take away the superficial and harmful connection of phones and social media. Children still yearn for the fulfillment of genuine connection, and the obvious and primary answer for that need is parents. And right there is both the real problem and the solution: most parents don’t know how to unconditionally love their children, the kind of love that provides the ultimate connection children need.

The emphasis is on unconditional love, the kind of love without the destructive effects of disappointment, guilt, obligation, and anger. Parents need to learn how to unconditionally love their children. And the course material has already been created and tested for thirty years. Visit the free websites RealLoveParents.com and RealLove.com and learn how to find unconditional love and share it with your children.

Beautiful breakdown. Thank you for banging this drum so clearly.

We all recognize that children are just first right? That adults suffer in these ways too?