Suicide Rates Are up for Gen Z Across the Anglosphere, Especially for Girls

It’s not just anxiety, depression, and self-harm. (Part 3 of Youth Mental Health Crisis is International)

This is Zach Rausch’s third post on international mental health trends. As with his previous two posts, Zach has drawn from a large number of studies, developed clear graphing methods, and told a compelling story about what changed, and where, since the early 2010s. As with his previous posts, I believe Zach has made some real discoveries here. He demonstrates a pattern in girls’ suicide rates that has not been noticed or much discussed, as far as we can tell.

—Jon Haidt

In early 2021, Jon told me that we needed to figure out “just how international” the youth mental health crisis is. After examining data from the Anglosphere (U.S., UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) and Nordic nations (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland), I’ve found that one trend stands out above all others: the spike in anxiety, depression, and self-harm among adolescent girls that began in the early 2010s.

Figure 1 shows the surge in self-harm rates in the five Anglosphere nations:

Adolescent Self-harm Episodes in Five Anglo Nations

Figure 1. Since 2010, rates of self-harm episodes have increased for adolescents in the Anglosphere countries, especially for girls. For data on all sources, and larger versions of the graphs, see Rausch and Haidt (2023). Before 2010, there was not much happening. By 2015, self-harm episodes were at record-high levels in all five countries. (Data for Canada is limited to Ontario province, which contains nearly 40% of the population of Canada.)

I have added a shaded area on all graphs from 2010 to 2015, which is the period that Jon calls “The Great Rewiring of Childhood” in his forthcoming book, The Anxious Generation. It’s the five-year period when adolescence changed to a phone-based form; adolescents went from nearly all owning flip phones (or other basic phones) to nearly all owning smartphones with high-speed data plans and continuous (and nearly unlimited) access to the internet and social media. This is the five-year period in which adolescent mental health began to deteriorate around the Western world.

But not all researchers are convinced that the mental health crisis is so dire, or even that it is real. Some skeptics have raised a number of concerns, particularly about suicide rates—a topic that we have not said much about on this Substack because we have been trying to figure it out for ourselves.

Suicide is a “hard metric”—it is a number carefully counted (not estimated) by national governments. Anxiety and depression are more difficult to measure accurately. And so, if youth suicide rates were unchanged or even declining since 2010 it would significantly complicate our story that the transition from play-based childhood to phone-based childhood is a major cause of the international decline in adolescent mental health.

In fact, some do point to data showing that rates of suicide among young people have been steady or declining since the 2000s. See, for example, the WHO Mortality Database which provides suicide rate data for 15-19 year-olds from many nations around the world (Figure from Our World in Data):

[Note: Figure 1 above was added on April 20th, 2024. Zach replaced the old figure because the original showed trends from a different database: the WHO GHE. The WHO GHE has been underestimating known suicide rates since the early 2010s across many nations with high quality death registration data. The WHO Mortality Database appears to be more accurate. Read more about the WHO GHE here.]

As can be seen in Figure 1, it is true that overall suicide rates are not increasing across all nations.1 But it would be a mistake to conclude that the United States is unique, or that there is not a worrying international trend in youth suicide rates. Here are four reasons why:

Those graphs fail to break results down by sex. The mental health crisis is gendered, with girls showing the most substantial and rapid changes in mental illness since the early 2010s.

They fail to consider how young people are doing relative to older people in each country. Anxiety rates are surging among youth, while only slightly increasing for U.S. adults. Perhaps suicide rates overall are dropping, but not for young people, or not as fast for young people. If so, we’d still want to know: why are young people not sharing in the decline in suicide?

They don’t break out data for 10-14-year-olds, where there are the largest relative increases since 2010 in poor mental health. (These effects are harder to see on graphs that also show older age groups because of the low base rates for 10-14-year-olds).

They fail to consider cultural variation. While there has been a global decline in suicide rates over the past century, particularly among older adults in non-western nations, my previous posts have found significant regional and cultural effects on mental health outcomes. Thus, some cultural variation should be expected, rather than immediately seen as counter-evidence.2

Thus, we need to look more closely at the suicide data because many of the analyses being done are conducted in ways that might obscure real changes, particularly for girls and young women.

So let’s increase the resolution and see if a trend emerges. In this post, I examine suicide rates among Gen Z in the five Anglosphere countries, comparing rates between sexes, between age groups, and with earlier generations when they were in their youth. It turns out that in each of the five Anglosphere nations, suicide rates among adolescent girls (ages 10-19) are at all-time highs (since modern records have been kept). Suicide rates for Gen Z girls now surpass those seen during the adolescent and young adult years of Millennials (born 1981-1995), Gen X (born 1965-1980), and Boomers (born 1945-1964).

For adolescent boys, I’ll show that the changes are more varied across nations and that only some nations are reaching historical peaks. I was surprised to discover that it was the Gen X boys who showed the most consistent peaks in suicide rates (back in the 1980s and early 1990s) across the five Anglosphere nations.

In short, the suicide data among Gen Z girls is consistent with the story we have told on this Substack about rising anxiety, depression, and self-harm. The adolescent mental health crisis is real, international, and gendered. And if that is true, then the many theories put forth to explain the mental health crisis in the U.S. may have only limited explanatory power. We must also look for something that changed in the lives of adolescents, and especially adolescent girls, in many countries simultaneously, in the years around 2010.

Suicide Rates in the United States

The Centers for Disease Control’s Fatal Injury Report reveals a troubling trend: While suicide rates for both sexes had been declining since the 1980s, they began rising in the early 2000s for older adults and then for adolescents from 2008 onwards. Among the most notable recent trends is that the rates for girls aged 10-24 rose by approximately 77% between 2007-2009 and 2017-2019 (Note: To determine the relative change in suicide rates throughout this post, I average the suicide rate for the three years before the Great Rewiring, 2007-2009, and I compare it to the three years before the COVID pandemic began in 2020––in this case, 2017-2019. This gives us a stable and consistent measure across nations that is not contaminated by the effects of the pandemic and its associated restrictions, which varied in severity across nations.)

U.S. Suicide Rates (Ages 10-64)

Figure 2. U.S. Adolescent and Adult Suicide Rates (Ages 10-59), 1981-2021. (Source: CDC WISQARS Fatal Injury Report, and data from 1981-2000). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points).

But because the baseline rates are much lower for young people (especially younger adolescents) than adults, it is difficult to see these rapidly changing rates. The trends become clearer when we zoom in and just plot the rates for adolescents:

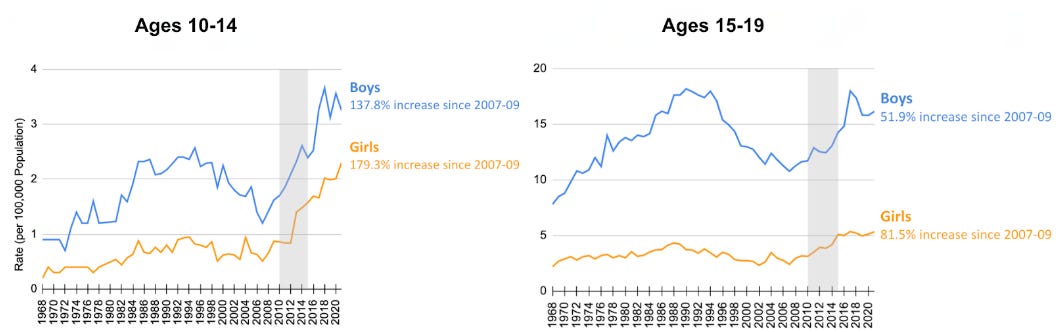

U.S. Adolescent Suicide Rates (Ages 10-19)

Figure 3. U.S. Adolescent Suicide Rates (Ages 10-14 and 15-19), 1968-2021. (Source: CDC WISQARS Fatal Injury Report, and CDC WONDER). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points). I included the data points from 1968-80 to see even longer historical trends.

Figure 3 shows four facts that are important for understanding adolescent suicide: (1) Boys have higher rates of suicide than girls, (2) since 2010, boys have had greater absolute increases in suicide (the total number of additional suicides per year), while girls have had higher relative increases (the percentage increase over time), (3) girls have now reached higher suicide rates than any period previously recorded, and (4) boys have followed a “roller-coaster” pattern of suicide with a rise beginning in the 60s, a fall beginning in 90s, and a rise in the late 2000s and 2010s. (Fact #4 will be the focus of a future post on this Substack.)3

Regarding the first fact, the ratio of suicides among teenage boys to teenage girls stands at a staggering 3:1. Understanding this significant disparity is crucial for any discussion about suicide. Suicidologists have found that this gender gap in suicide is partly due to the fact that boys tend to use more lethal means than girls, and have higher suicidal intent. Regarding methods, boys tend to use guns or asphyxiation, while girls are more likely to use more reversible methods, such as overdosing on pills (Note that rates of asphyxiation among girls have been rising in recent years).4

In fact, the differences in these methods (and intent) lead to what is called the gender paradox in suicide: although girls’ rates of suicide are much lower than boys’, girls report higher rates of suicidal ideation (SI) and make more suicide attempts (SA) than boys.5

The third fact visible in Figure 3—that adolescent girls in the 2010s are outpacing the suicide rates of all previous decades before them—guides us to look closer at the factors influencing gender-specific suicide patterns, as well as any unique generational effect in the data.

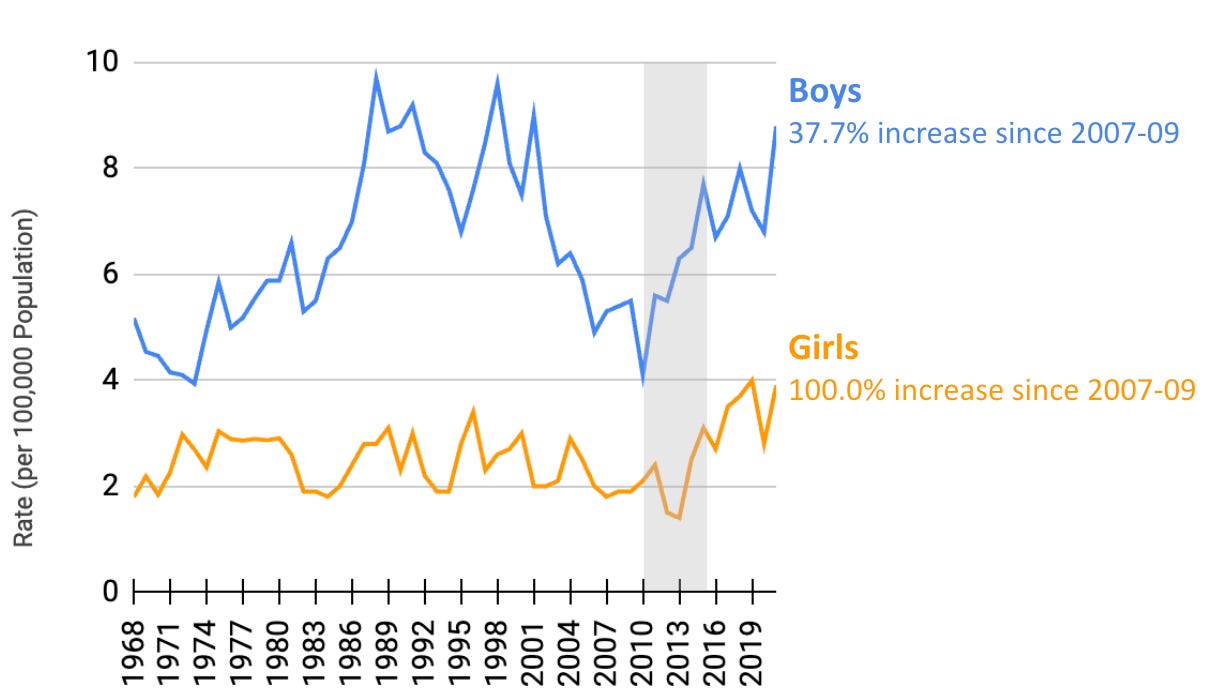

So let us compare the suicide rates of Gen Z boys and girls (those born after 1995) to earlier generations when they were at that same age. Figure 4 plots the average rate of suicide for three age groups of young people (10-14, 15-19, 20-24).6 As you can see, the lines slope upwards because rates increase from early adolescence through the early 20s. You can also see that the lines for Gen Z (in blue) are higher than for previous generations, for both sexes but especially for girls. Gen Z girls and young women in all three age groups have died by suicide at much higher rates than any previous generation. Gen Z boys, in contrast, have died by suicide at rates that were only a little higher than those of previous generations.

Suicide Rates by Age Groups and Generations (U.S.)

Figure 4. U.S. suicide rates across the lifespan by generation. Gen Z females have higher rates than all other generations at the same age. Gen Z males have higher rates than Boomers and Millennials but look similar to Gen X until their early 20s. Note that Gen Z data for those ages 20-24 only include 2020 and 2021, the COVID years (this is true for all nations) (Source: CDC WISQARS Fatal Injury Report, and CDC WONDER). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points).

In sum, suicide rates began rising in the late 2000s, with an acceleration in the early 2010s, for both sexes. Since the late 2000s, both boys and girls also had higher relative increases in suicide than young adults and middle-aged adults. Boys and young men today are back at the peak rates of suicide last seen in the late 1980s, while girls and young women are venturing into previously uncharted territory.

Based upon these U.S. results, we can identify a pattern with 8 elements, which I’ll use to compare across the other Anglosphere nations.

For girls:

Suicide rates began to rise in the late 2000s or early 2010s.

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for girls and young women (10-24) than for adult women (25+).

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for adolescent girls than for boys.

Gen Z girls’ suicide rates were and are higher than all previous generations at the same age.

For boys:

Suicide rates rose from the 1960s through the 1980s and fell in the 1990s.

Suicide rates increased again in the 2010s.

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09). was higher for boys and young men (10-24) than for adult men (25+).

Gen Z boys’ suicide rates were and are high compared to Millennials and Boomers, although they are not far from those of Gen X.

The United Kingdom

To examine suicide trends in the UK, I used the comprehensive data from the UK Office of National Statistics which provides rates segmented by age and sex. Note that the data I have pertains specifically to England and Wales, which contain about 89% of the population of the UK.

Like the United States, England and Wales saw a decline in suicide through the 1980s, especially among middle-aged women. From 1981 to 1994, the rates for adult women aged 45-64 in England and Wales fell dramatically—by 83% (rates for adult men also fell). However, during the same period, rates began rising for young males and females (though, young females did not rise nearly as much as the young males). The 80s and 90s reflect an important fact about suicide trends: changes among adults do not mean there will be equivalent changes among young people.

The mid-1990s marked a plateau in suicide rates until the 2010s when they began to rise again. Just like in the U.S., it was the younger girls (10-24) who had the sharpest rise.

England and Wales Suicide Rates (Ages 15-59)

Figure 5. England and Wales suicide rates (Ages 15-64), 1981-2021. (Source: Nasir, John, & Mais, 2022, UK Office of National Statistics). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points). Note that there were changes to suicide accounting in 2018.7 Note also that the rates are extremely low for the youngest group, the 10-14-year-olds. The number of such suicides in England and Wales is usually below 10 per year, so I do not include a separate graph for them. Rates for teens are also low relative to the United States).

When we zoom in on the teenage rates (ages 15-19), trends in England and Wales resemble the “roller coaster” pattern in the U.S. for boys: there’s a rise in the 1970s, a surge in the early 80s—with peaks in the late 80s and early 90s—a plummet that begins in the late 90s, followed by a resurgence again in the early 2010s.

England and Wales Suicide Rates (Ages 15-19)

Figure 6. England and Wales teen suicide rates (Ages 15-19), 1968-2021. (Source: Nasir, John, & Mais, 2022, UK Office of National Statistics). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points).

For girls, rates remained generally steady with minor fluctuations since the late 1960s, until a big increase in the 2010s.

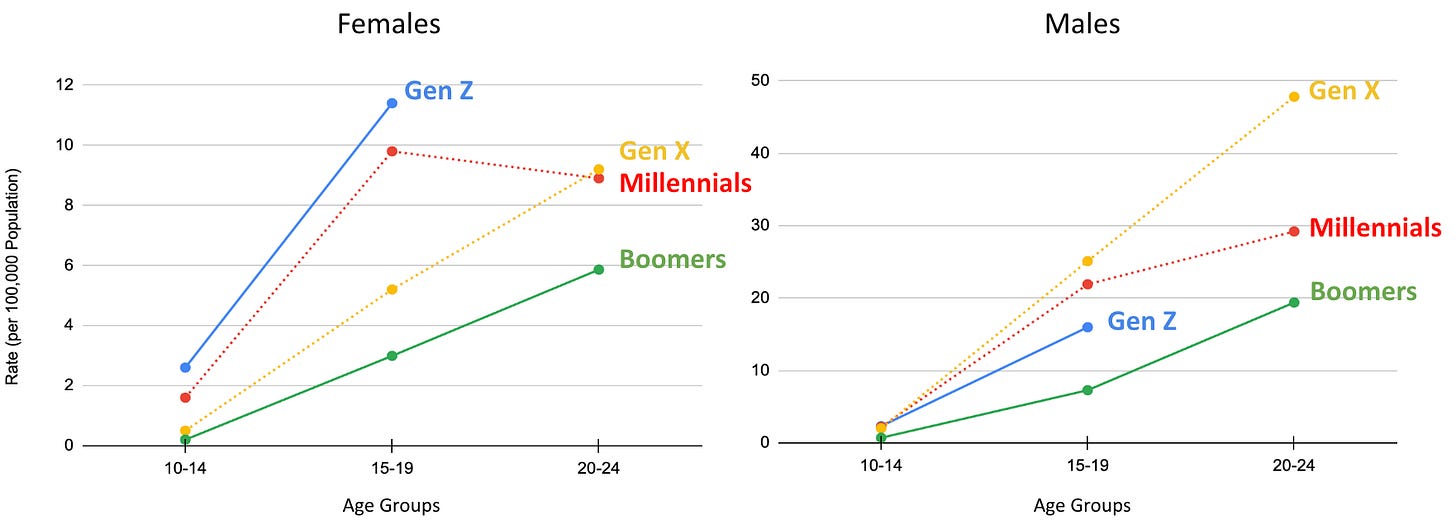

Applying a generational lens, we once again see gendered generational effects. As is the case in the U.S., Gen Z girls in England and Wales are exhibiting higher suicide rates than their predecessors.

Suicide Rates by Age Groups and Generations (England and Wales)

Figure 7. England and Wales suicide rates across the lifespan by generation. (Source: Nasir, John, & Mais, 2022, UK Office of National Statistics). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points).

Male trends are different. Gen Z males aged 15-19 have rates nearly identical to Gen X, but as they age into their early 20s, it is Gen X that increases the most, while Gen Z stays closer to the rates of boomers and millennials.

To sum up: The suicide data for girls in England and Wales closely follows the pattern seen among girls in the U.S., and the pattern for boys is similar among teenagers but differs as they move into their twenties. (Note: I use YES, NO, and MIXED to note when trends match the U.S. pattern.)

For girls:

Suicide rates began to rise in the late 2000s or early 2010s. (YES, although the sustained rise seems be begin slightly later than in the U.S., in 2014)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for girls and young women than for adult women. (YES)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for adolescent girls than for boys. (YES)

Gen Z girls’ suicide rates were and are higher than all previous generations at the same age. (YES)

For boys:

Suicide rates rose from the 1960s through the 1980s and fell in the 1990s. (YES. Although, the major decline began in the early 2000s)

Suicide rates increased in the 2010s. (YES)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for boys and young men than for adult men. (YES)

Gen Z boys rates were and are high compared to Millennials and Boomers, although they are not far from those of Gen X. (MIXED. Unlike the U.S., Gen Z males aged 15-19 have similar rates to Gen X, but they diverge in their 20s when Gen X increased most, while Gen Z stayed closer to the rates of Boomers and Millennials.)

Canada

In 1971, the Canadian government established Statistics Canada, an agency devoted to producing population-based statistics to understand their constituents. Statistics Canada provides the most extensive data on youth suicide in the country, which allows us to look at suicide trends over multiple decades. However, I have only been able to find suicide rate data for Canadian adults from 2000 onwards.

Figure 8 reveals that suicide rates remained relatively steady (with some fluctuations) for all age groups in the early 2000s, with noticeable increases among girls and young women in the 2010s.

Canada Suicide Rates (Ages 10-64)

Figure 8. Canadian suicide rates (Ages 10-64), 2000-2021. (Source: Skinner & McFaull with data from Statistics Canada). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points).

Focusing on adolescent rates, male teen suicide rates peaked in the 1980s and early 90s, paralleling trends in the U.S. and UK. We can also see that the pattern for both 10-14 and 15-19 year-olds since 2010 are similar: trends are fluctuating around a baseline for boys while getting worse for girls. (Note: The total number of suicides per year is very low for Canadian 10-14 year-olds, ranging between 10-30 girls per year and 10-30 boys per year, so the graphs are quite spiky.)

Canada Adolescent Suicide Rates (ages 10-19)

Figure 9. Canadian adolescent suicide rates (Ages 10-19), 1982-2021. (Source: Skinner & McFaull with data from Statistics Canada). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points). Similar to the UK, rates for younger Canadians (ages 10-14) are much lower than those in the United States. However, the rates are higher than in the UK (between .5 and 3 per 100,000). Note that I merged every two years together for the 10-14-year-olds to reduce the spikiness caused by low absolute numbers.

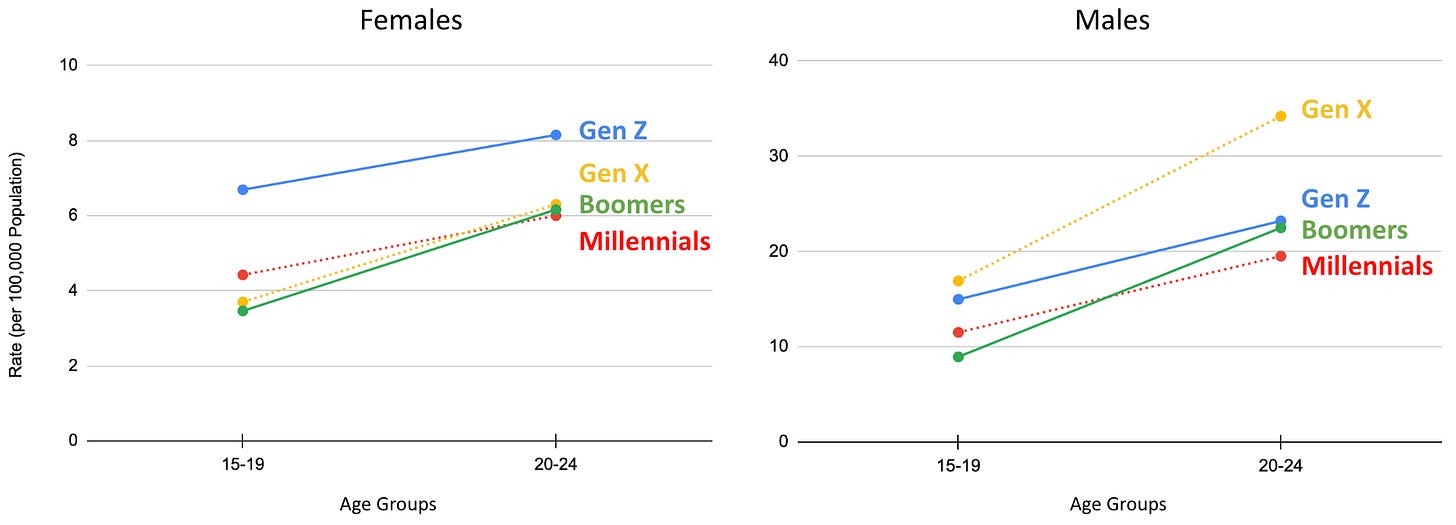

Generationally speaking—as can be seen in Figure 10—Gen Z Canadian girls echo their American peers, with higher rates among Gen Z than any other generation. For boys, the trends are different.

Suicide Rates by Age Groups and Generations (Canada)

Figure 10. Canadian suicide rates across the lifespan by generation. Gen Z females have higher rates than previous generations. Gen Z males have similar rates compared to Millennials. Gen X had significantly higher rates than all generations during their teen years. Note that I only have access to data of 10-19-year-olds since 1982, so I cannot include the Baby Boomer data or Gen X data when they were 20-24. (Source: Skinner & McFaull with data from Statistics Canada). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points).

Overall, Canadian girls' suicide trends closely mirror those in the U.S. and UK, with Gen Z girls having higher rates than all previous generations at the same age. Unlike the U.S. and UK, Gen Z boys look more similar to Millennial boys than Gen X. The largest and most striking finding is that Gen X teen boys had much higher suicide rates than the generation of boys who came after them.

The basic pattern among girls held:

For girls:

Suicide rates began to rise in the late 2000s or early 2010s. (YES)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s was higher for girls and young women than for adult women. (YES)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s was higher for adolescent girls than for boys. (YES)

Gen Z girls’ suicide rates were and are higher than all previous generations at the same age. (YES)

For boys:

Suicide rates rose from the 1960s through the 1980s and fell in the 1990s. (MIXED. I do not have data before the 1980s, so I do not know if rates had been rising previously)

Suicide rates increased in the 2010s. (YES)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s was higher for boys and young men than for adult men. (YES)

Gen Z boys’ rates were and are high compared to Millennials and Boomers, although they are not far from those of Gen X. (NO. Unlike the U.S., Gen Z boys’ rates were more like those of Millennials than Gen X. Gen X rates of suicide were higher than other generations.

4. Australia

To examine suicide trends in Australia, I used data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. For larger age group comparisons, they provide data for 15-24, 25-44, and 25-64 year-olds from 1981 to 2018.

Figure 11 shows that rates of suicide were declining or steady for women and girls in the 1980s and 90s, followed by a rise in the 2010s.

Australia Suicide Rates (Ages 15-64)

Figure 11. Australian suicide rates (Ages 15-64), 1981-2018. (Source: Data tables: 2021 National Mortality Database—Suicide, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points). (Since data collection ended in 2018, the relative comparison was between 2007-09 and 2016-2018).

Males, especially boys and young men, saw a rise in the 80s and 90s, a decrease till the mid-2000s, and then a subsequent increase in the 2010s—this recent surge was more pronounced among the youngest age group (15-24). Older males, aged 45 and above, saw a gradual decline in rates throughout the 80s and 90s, but have experienced a steady climb since the early 2000s.

The Institute of Health and Welfare also provides data for 5-year age groups going back to 1906, offering a unique perspective into long-term trends for adolescents.

Like the other nations reviewed so far, we see the roller coaster pattern for boys: there’s a large rise that begins in the 1960s and peaks in the late 1980s/early 1990s, then falls sharply in the mid-90s. Like the U.S. and UK, those rates began rising again in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

Australia Teen Suicide Rates (Ages 15-19)

Figure 12. Australian teen suicide rates (Ages 15-19), 1907-2021. (Source: Data tables: 2021 National Mortality Database—Suicide, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points). I was unable to find suicide rate data for the 10-14-year-olds.

For girls, rates were generally steady until the 1980s, when suicides began to rise slowly, and then accelerated upwards in the early 2010s (where they continued to fluctuate at those high rates).

The generational analysis makes the Australian trends of rising suicide rates among girls very clear. As you can see in Figure 13, Gen Z Australian girls have the highest rates compared to any preceding generation during their youth. Gen Z boys, on the other hand, mirror the trends of Gen X during their teens but diverge as they transition into their twenties—with Gen X continuing their high rates, while Gen Z looks similar to Boomers and Millennials (just like the trends in England and Wales).

Suicide Rates by Age Groups and Generations (Australia)

Figure 13. Australian suicide rates across the lifespan by generation. Gen Z females have higher rates than all previous generations. Gen Z males have higher rates than Boomers and Millennials and look similar to Gen X in their teens. Gen X jumps higher than all other generations when they are in their early 20s. (Source: Data tables: 2021 National Mortality Database—Suicide, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points). I was unable to find suicide rate data for 10-14 year-olds.

In sum, the U.S. pattern holds for Australian girls, while the story for boys looks more like England and Wales.

For girls:

Suicide rates began to rise in the late 2000s or early 2010s. (YES)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for girls and young women than for adult women. (YES)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for adolescent girls than for boys. (YES)

Gen Z girls’ suicide rates were and are higher than all previous generations at the same age. (YES)

For boys:

Suicide rates rose from the 1960s through the 1980s and fell in the 1990s. (YES)

Suicide rates increased in the 2010s. (YES)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for boys and young men than for adult men. (YES)

Gen Z boys rates were and are high compared to Millennials and Boomers, although they are not far from those of Gen X. (MIXED. Gen Z males aged 15-19 have similar rates to Gen X, but they diverge in their 20s when Gen X increased most, while Gen Z stayed closer to the rates of Boomers and Millennials.)

New Zealand

Using data from The Ministry of Health of New Zealand, I examined suicide trends among three age groups: 15-24, 25-44, and 45-64.

For females, suicide rates declined or were steady through the 1980s. But then, in the 1990s, rates for younger girls (15-24) began to rise and surpassed the rates of all older women. Those high rates stabilized through the 2000s, followed by increases in the 2010s.

For younger males, there was the similar cross-national rise and fall of male suicide in the 1980s and 1990s (rates for older males fell through this period). In the early 2000s, rates increased for older adults and continued to fall for younger males. In 2018, the rates for all male age groups were almost the same.

New Zealand Suicide Rates (Ages 15-64)

Figure 14. New Zealand suicide rates (Ages 15-24), 1981-2018. 2018 is the last year that I have found data for. (Source: New Zealand Ministry of Health, data before 2000 was provided by staff at NZ MIH through email). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points). (Since data collection ended in 2018, the relative comparison was between 2007-09 and 2016-2018).

Zooming in on adolescent data, which goes back to 1946, offers additional context and understanding. Figure 18 shows that there was an initial period of low suicide rates for both teen boys and girls up until the 1980s. (Note: Yearly suicide deaths are below 10 per year for those 10-14. Because of this, I do not include the graph on their suicide rates).

New Zealand Teen Suicide Rates (Ages 15-19)

Figure 15. New Zealand teen suicide rates (Ages 15-19), 1948-2018. 2018 is the last year that I have found data for. (Source: New Zealand Ministry of Health, data before 2000 was provided by staff at NZ MIH through email). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points). (You can see the graph for 10-14-year-olds in section 5.2.1 of our collaborative review doc: Anglo Suicide Rates Since 2010.) Note that I merged every two years together to reduce the spikiness caused by low absolute numbers. (Since data collection ended in 2018, the relative comparison was between 2007-09 and 2016-2018).

For teen boys, rates began to slowly rise in the 60s, grow more rapidly in the 80s, fall in the 90s, and then stabilize at higher rates throughout the 2010s (though with significant spikes and dips at those high levels).

For girls, suicides began rising a bit later, in the early 90s, dipped toward the end of the decade, and then rose again in the mid-2000s, sustaining high rates up to 2018 (the last year for which I could find data).

The generational analysis shows unique trends, with Millennial girls experiencing elevated rates of suicide, along with Gen Z. Nonetheless, Gen Z girls still have higher suicide rates than the generations before them. (Note: because I have data only up through 2018, I do not yet have data on Gen Z in their 20s).

Suicide Rates by Age Groups and Generations (New Zealand)

Figure 16. New Zealand suicide rates across the lifespan by generation. Gen Z females have higher rates than all other generations, though I do not have data to see their rates as 20-24 year-olds. Gen Z males have lower rates than Gen X and millennials did in their teen years. (Source: New Zealand Ministry of Health, data before 2000 was provided by staff at NZ MIH through email). (spreadsheet with graphs and data points).

Interestingly, Gen Z boys in New Zealand have lower rates of suicide than both Gen X and Millennials at that same age. The Gen X male cohort is consistent with the trends of the other Anglo nations, exhibiting elevated rates throughout their teens and into young adulthood.

In sum, New Zealand partially follows the basic pattern observed in the other nations, with a few distinctive features.

For girls:

Suicide rates began to rise in the late 2000s or early 2010s. (MIXED. Interestingly, they do rise for the broader age group of 15-24, but are not rising when only looking at the 15-19 age group.)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for girls and young women than for adult women. (YES)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for adolescent girls than for boys. (MIXED. They are higher for the broader age group of 15-24, but are not when only looking at the 15-19 age group.)

Gen Z girls’ suicide rates were and are higher than all previous generations at the same age. (YES)

For boys:

Suicide rates rose from the 1960s through the 1980s and fell in the 1990s. (YES)

Suicide rates increased in the 2010s. (NO)

The relative rise (the percent change) of suicide since the late 2000s (2007-09) was higher for boys and young men than for adult men. (NO)

Gen Z boys’ rates were and are high compared to Millennials and Boomers, although they are not far from those of Gen X. (NO. Gen Z boys diverge from the cross-national trends, with their suicide rates being lower than both Millennials and Gen X.)

Conclusion

Over the last century, global suicide rates have been in decline, especially among older adults and particularly among those living in non-western nations. But this broad historical trend masks a very different story that emerges when we focus on adolescent girls in many Western nations. In all five Anglosphere nations, Gen Z girls and young women had the highest rates of suicide of any recent generation. The same was not true of Gen Z boys and young men.

Across each of my three posts on this Substack, I have found the same trend repeatedly: the mental health of adolescent girls in nations across the Anglo world became significantly worse in the early 2010s. It wasn’t just large increases in self-reports of anxiety and depression; it was also behaviors, including self-harm, and suicide. Boys have struggled enormously too, but their outcomes have been more varied across nations, and they do not so often show an elbow in the late 2000s or early 2010s.

As we saw in this post, the pattern found for girls in the U.S. was also found in the UK, Canada, and Australia. The pattern was only partially replicated in New Zealand (which has by far the smallest population of the five nations, making trend lines fluctuate more).

The basic pattern for boys was less consistent but revealed an important backstory: across all five nations, suicide rates were at historically high levels in the 1980s. In all five nations, rates began to plummet in the 1990s and early 2000s. And in four of these nations (though Canadian boys did not rise much), rates began rising again in the late 2000s or early 2010s. The story for boys is as much a story about a previous generation, Generation X (born 1965-1980), as it is about Generation Z (born 1996-2012). This “roller coaster” pattern of suicide rates was crystal clear for boys in the U.S., UK, and Australia. (In a future post, I will argue that the unprecedented global emission of lead into the atmosphere from leaded gasoline in the postwar years, followed by its banning in the 1980s, is a plausible explanation of the rapid rise of suicide rates and crime rates among boys beginning in the 1960s and the still-unexplained sudden fall those rates in the 1990s. See here, here, here, here, here, and here for research on the impact of early lead exposure on brain development and its larger effects on boys.)

I want to reiterate that suicide rates among adolescent girls are almost always low relative to older women, boys, and especially to adult men. In fact, in the United States, suicide rates among women are highest in their fifties, while among men rates are highest in their 80s. Efforts to reduce suicide should be made for all impacted populations.

At the same time, the spike in suicides among adolescent girls is so new and so large that it calls for intense efforts to identify the causes, and for efforts to change whatever is causing it. One of the most important facts about adolescent suicidality is that the motives among young people are often different than those among adults. Adolescents are much more likely to commit suicide as a result of interpersonal problems, while adults have more varied motivations—including illnesses and financial setbacks, as well as interpersonal reasons.

There was one seismic shift in how interpersonal relationships work that fits the timing well: the global and simultaneous migration of adolescent social life onto smartphones and social media platforms, which happened roughly between 2010 and 2015. In The Anxious Generation, Jon shows that this evolution fundamentally altered the dynamics of interpersonal relationships, shifting childhood from one that was (generally) in-person, embodied, synchronous, and play-based to one that was (generally) virtual, disembodied, largely asynchronous, and phone-based. Since the early 2010s, stable in-person communities and relationships have rapidly disintegrated, as transient networks of low-investment relationships took their place. Figure 19 shows that American teens and young adults were already socially distanced from each other by 2019, before covid restrictions were imposed on them.

Time Spent With Friends

Figure 19. Total number of minutes spent with friends per day (annual daily average). Kannan & Veazie (2023) analyzing the American Time Use Study. Replotted by Zach.

The sudden switch from play-based childhood to phone-based childhood is—we believe—the leading candidate for being the major cause of the international collapse of adolescent mental health.8 The evidence of causation is particularly strong for girls. In fact, nobody has yet put forth an alternative theory—one that can explain why the same thing happened at the same time in so many countries. Jean Twenge recently considered thirteen such theories that have been proposed to explain trends in the U.S., and she showed that they don’t even work in the U.S., let alone internationally.

If you have an alternative theory, we’d love to hear it. Please put it in the comments. Just make sure your theory applies all over the Anglosphere.

For more: Check out our collaborative review document, Anglo Suicide Rates Since 2010. This houses all of the studies and data I have presented in this essay. Please add studies, comments, and criticisms.

David Stein notes that “OWiD data, at least for the U.S., does not align with CDC data and outright reverses some trends for youth.” See his Tweet noting some of the discrepancy with CDC data. OWiD uses the WHO’s Global Health Estimate data. You can see their estimation-based methodology here. (Check out Stein’s Substack, The Shores of Academia.)

Countries with higher levels of individualism (where young people are less rooted in binding communities) appear to have been more affected compared to less individualistic nations (which is why I began my posts by examining the Anglosphere and Nordic nations)

There are other important facts about adolescent suicide to consider. For example, suicide rates are typically higher among LGBTQ youth compared to heterosexual youth and higher among White youth than Black youth. To see U.S. adolescent suicide trends broken down by race and sexual orientation, see Appendix C and D of the collaborative review doc, Adolescent Mood Disorders Since 2010, create by Jon, Jean Twenge, and me.) Other important demographic factors to consider include variation by social class, conservatism, and religiosity—important topics I plan to discuss in future posts.

Note that adolescent suicide methods change over time. The biggest change in mechanism for girls since the 1980s appears to be in rates of suicide by asphyxiation (See Joseph et al. (2022) for U.S, Skinner & McFaull (2012) for Canada, Stefanac et al. (2019) for Australia, and Beautrais (2000) for New Zealand. However, beside Joseph et al., these studies do not look at mechanisms since 2015 (Thus, they are not helpful in helping discern changes over the past decade).

Data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey highlights this gender paradox. While both sexes have experienced an increase in SI and SA since 2010, girls’ rates are consistently higher, with their spike being especially pronounced in recent years. Other studies analyzing trends between 2008 and 2021 reinforce the gendered trends in SI and SA. One study, looking at SI and SA encounters at 31 children’s hospitals from 2008 through 2015, found a doubling in rates through the study period, with the largest rise amongst adolescent girls. Another trend in these data is that suicide rates fluctuate seasonally, with highest rates in the Fall and Spring, and lowest rates in the summers. Peter Gray writes extensively on this topic, arguing that these trends point to modern schooling as a major cause of adolescent suicide. Importantly, this may be a culture-bound effect primarily occurring in Western nations. See Yang & Feldman (2018) for evidence of non-suicidal self-injury being more common among males in China. Also see Zhao, Peng, and Peng (1994) showing how Chinese women had higher rates of suicide than men. Though, rates among Chinese women have fallen significantly since the 1990s.

To analyze generational trends in suicide rates, I plotted the average suicide rates based on specific age groups (e.g., 10-14, 15-19) for distinct generations. Take the age group 15-19 as an example: from 2000-2010, this age group was entirely composed of Millennials. In 1999, the oldest members of this age group were still Gen Xers, and by 2011, the youngest members had become Gen Zers. So, I calculated the average suicide rate for the 15-19 age bracket between 2000-2010 to represent the Millennial generation's average rate during those ages. I used the same approach for other age brackets and generations, allowing for a clearer picture of generational patterns in suicide beyond just temporal changes.

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health states that “official records of deaths by suicide may underestimate true numbers of deaths where suicidal intent was present, due to the high burden of proof that coroners require to determine official cause of death. However, in 2018, in England and Wales the standard of proof used by coroners to determine whether a death was caused by suicide was lowered to the “civil standard” (i.e “balance of probabilities” where previously it had been “beyond reasonable doubt”), and is likely to affect official records (Scotland and Northern Ireland are not affected).” Thus, the rise of suicide rates since 2018 may be impacted by this change in reporting.

Regarding the suicide trends: While I focus on the impact of the phone-based childhood, it is important to note that suicide is a complex and rare event, and national suicide rates are influenced by many interacting factors, such as the prevalence of guns in homes (and access to other lethal means), the difficulty of getting emergency psychiatric care (and general quality of suicide prevention and support services), drug and alcohol use and addiction, family dysfunction, genetic factors and pre-dispositions to mental illness, and the level of social integration within a community. In this post, my goal was to examine the interpersonal factors which significantly changed across all five nations in the early 2010s and would impact adolescent girls most acutely.

Teach a nation’s white children that they should hate themselves, their parents, their families and their nation and this is the result.

With their culture completely eroded to the point of being seen as a disease among their peers and bingo, you just created an extremely unstable situation. The ones that don’t turn “trans” so they can join the new culture of victimhood kill themselves. Then the ones that do turn trans, kill themselves once they realize they’ve destroyed their future as a human being.

Great job, liberal America, globalists, and other evil fucks across the globe.

What the data seems to show is fairly stable numbers for both genders up until the very early sixties, followed by a breakout and continued upward trend since. Less pronounced in girls but clearly shown, and accelerating for girls. I would argue that the issue isnt a play based vs phone based childhood, but a play/family based vs tech/isolated childhood. The beginning of the 1960's marked the rise of women entering the workforce, 2 income families, latchkey kids phenomenon, and the penetration of televisions into the average household. Its only gotten more isolating since. The smartphone is just another tool to isolate kids further from each other and from their families.