Does Social Media Use at One Time Predict Teen Depression at a Later Time?

Reviewing longitudinal evidence

Many studies have found a correlation between heavy social media use and higher levels of internalizing disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression) in adolescents, especially in girls. However, most of these studies are cross-sectional: they measure social media use and depression symptoms at the same point in time. Whether the association observed in cross-sectional studies extends to longitudinal studies — which follow the same participants over months or years and measure both social media use and mental health — is a critical question. Luckily, more and more data is available from such longitudinal studies, and researchers are leveraging these datasets to estimate whether earlier levels of one variable predict later changes in the other.

In this post, we provide a review of six relevant longitudinal studies through the lens of two contrasting hypotheses from researchers: social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, author of The Anxious Generation, and developmental psychologist Candice Odgers. Our jumping off point is the 2024 debate between Haidt and Odgers.

The first hypothesis, put forth by Haidt in “The Anxious Generation” (“TAG”) and his subsequent work, we’ll call forward predictability: earlier social media use predicts subsequent poor mental health. Haidt proposes that the social pressures and addictive design of social media pulls some teens (especially girls) to heavy use, which puts them at higher risk for depression and anxiety by multiple pathways, including social comparison, perfectionism, and emotional contagion. Haidt, Zach Rausch, and Jean Twenge compiled empirical evidence regarding this claim in a collaborative review document, starting in 2019.

The second hypothesis, forwarded by Odgers, we will refer to as reverse predictability: earlier poor mental health predicts subsequent social media use, but not the other way around. Odgers made this case in a high profile critique of “The Anxious Generation” in Nature:

When associations over time are found, they suggest not that social-media use predicts or causes depression, but that young people who already have mental-health problems use such platforms more often or in different ways from their healthy peers. [Emphasis added]

This argument, which directly challenges Haidt’s argument that heavy social media use predicts future mental health problems, has since been echoed by several researchers and writers.

Below we review the evidence Odgers puts forth in favor of the Reverse viewpoint, and we introduce three high-quality studies that provide evidence for the Forward hypothesis. Then we discuss the limitations of current longitudinal research and what these limitations mean for policymakers.

Some Background Before We Begin

Before we get to the studies themselves, it’s important to understand the basics of a longitudinal study and the scope of our analysis. We recommend all readers start with the first two subsections below: “Longitudinal Studies: The Basics” and “Our Focus: Social Media Use, Internalizing Disorders, and Adolescents”. After that, readers interested in more technical details can continue with the remaining subsections on quantifying predictability and the distinction between prediction and causation — but those are optional and may be skipped.

Longitudinal Studies: The Basics

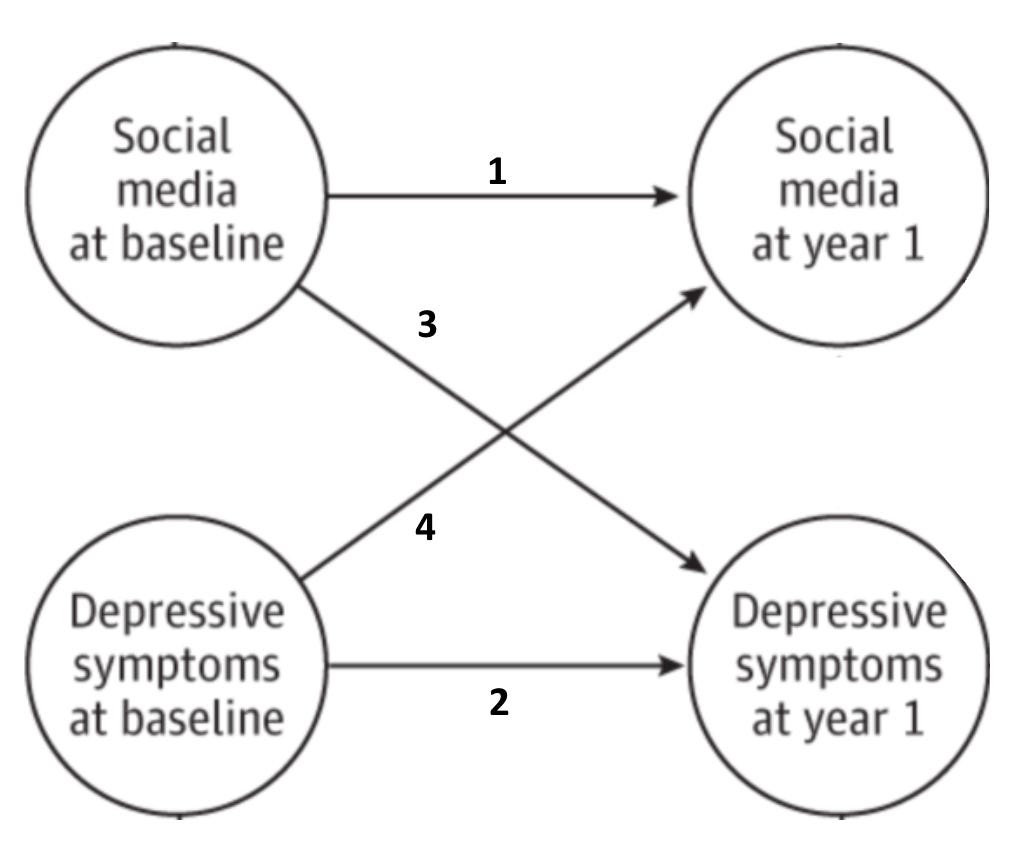

Longitudinal studies follow the same participants over time, measuring social media use (SMU) and depression (or other mental health variables) at multiple “waves,” often spaced months or a year apart. Researchers try to leverage this design to estimate whether earlier levels (or changes) of one variable predict later levels (or changes) in the other. In most studies there are four possible pathways of interest:

The association of past social media use (SMU) with future SMU

The association of past depression with future depression

The association of past SMU with future depression

The association of past depression with future SMU

The picture below is a simple illustration of these pathways, adapted from Figure 1 in Nagata et al. 2025. This post focuses on pathway 3 (forward) and pathway 4 (reverse) pathways.

Our Focus: Social Media Use, Internalizing Disorders, and Adolescents

Because Odgers directly challenges the core arguments of The Anxious Generation (TAG), we focus here on evaluating her claims about reverse predictability in that context. In TAG, Haidt claims that heavy social media use causes increases of internalizing disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression, self-harm) among adolescents. He further argues that this causal relationship helps explain the relatively sudden population-wide increase in internalizing disorders that began in multiple Western nations in the early 2010s.

We therefore evaluate studies by how well they test these claims: Does the study provide evidence that social media use is linked to internalizing disorders among adolescents? Studies that include adults, or that look at other outcomes such as life satisfaction, are less useful.1

Figure 1. Between 2010 and 2019, internalizing disorders such as anxiety, depression, and anorexia became more prevalent compared to other mental illnesses.

We Focus on Forward vs. Reverse Predictability, but There are Two Other Options

As well as arguing for reverse predictability, Odgers and others sometimes argue that there’s no relationship between social media and depressive symptoms. In other words, they sometimes argue that there’s no relationship along pathways 3 and 4 in the diagram above.

A final possibility is that there are associations in both directions; we will refer to this as reciprocal predictability, or reciprocity. A possible explanation for reciprocity could be the following: teens who are prone to depression are more strongly motivated to turn to social media, and that increased time on social media makes them even more depressed. The possibility of reciprocity is worth noting, because a reciprocal relationship would still mean social media use is associated with harm.

For simplicity, this post focuses on forward and reverse predictability.

Quantifying Predictability

There are myriad ways to define and estimate a measure of predictability or association. In these studies, the researchers typically codify the relationship through an estimate from a statistical model. The measure of predictability therefore depends on the statistical model, rather than being defined independently from it.

Rather than dive into the validity of this approach or whether the proposed statistical models are correct, we focus merely on interpreting the results as they are presented in each paper; in essence, we give the researchers the benefit of the doubt that their proposed statistical model is relevant and useful. This may not be the case, but interrogating the models in detail is outside of the scope of this review.

We Focus on “Predictability,” Not Causality

We focus on “predictability” and associations rather than “causality” and causal effects. We follow the conventions in this literature, where researchers typically estimate whether changes in social media use at one time point are associated with, or predict, changes in depression at a later time point, and vice versa. While the underlying debate centers on causal claims (TAG argues that heavy social media use causes depression and anxiety), the longitudinal studies we examine are primarily designed to test predictive relationships over time.

Translating these predictive relationships into causal claims requires strong assumptions. None of the studies we review assess whether these causal assumptions were violated or were satisfied, making it difficult to determine whether their results directly support forward or reverse causality hypotheses. Instead, to simplify our discussion, and because researchers in this area focus primarily on prediction rather than causation, we also focus on predictive associations and do not evaluate the plausibility of assumptions required to make causal inferences from these longitudinal data.

Reverse predictability

In May 2024, Odgers provided a useful summary of her reverse predictability argument in The Atlantic in an essay titled “The Panic Over Smartphones Doesn’t Help Teens”:

When associations are found, things seem to work in the opposite direction from what we’ve been told: Recent research among adolescents—including among young-adolescent girls, along with a large review of 24 studies that followed people over time—suggests that early mental-health symptoms may predict later social-media use, but not the other way around. [Emphasis added]

To support this claim, Odgers points to three studies often cited as evidence for reverse predictability: Puukko et al. (2020), a six-year longitudinal study of adolescents; Heffer et al. (2019), a two-year longitudinal study; and Hancock et al. (2022), a review and meta-analysis of 226 studies, including 24 that were longitudinal. Let’s take a close look at each of these studies to assess what they can — and cannot — tell us about the relationship between adolescent depression and social media use.2

Study 1. Puukko et al. 2020

Puukko and colleagues (2020) conducted a six-year longitudinal study of 2,891 Finnish adolescents, tracking “active social media use” and depressive symptoms. They concluded that “depressive symptoms predicted small increases in active social media use during both early and late adolescence, whereas no evidence of the reverse relationship was found.” On the surface, this supports the reverse predictability hypothesis.

However, crucially, this study did not measure the participants’ time spent on social media. Instead, they focused on the amount of “active social media use,” which they define as “socially-oriented...use, such as sending messages, sharing updates, and liking other people’s doings….” Here are the items they used, which were answered on seven-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (“never”) to 7 (“all the time”):

“I follow my friends’ profiles, pictures, and updates,”

“I update my status and share content with others,”

“I chat (e.g., Whatsapp, Facebook, email),”

“I share pictures and picture updates of my doings taken with my phone (e.g., Instagram).”

This changes the implications of the research’s findings. The study can give us interesting insight into the interaction between depression and a specific type of “socio-digital participation” over time, but it cannot tell us whether or not social media use generally predicts depression.

To illustrate how the particular measure used in the study could lead to an erroneous conclusion about social media, consider the following analogy. Imagine we are investigating whether heavy sugar consumption is unhealthy. Now suppose that one study asked people only about their fruit consumption. Fruit is indeed high in sugar, but consuming whole fruits (which include fiber and many micronutrients) is among the healthiest ways to consume sugar. Furthermore, merely eating a lot of fruit will not necessarily make a person a heavy consumer of sugar overall. If it turned out that people who eat a lot of fruit are just as healthy as those who eat little, this would not disconfirm the hypothesis that high sugar intake is unhealthy. We’d want to find studies that included all sugar intake, including those forms that are expected to be less healthy, such as in candy, soda, and ultra-processed desserts.

Study 2. Hancock et al. 2022

Hancock and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of studies linking social media use with six forms of well-being: eudaimonic well-being, hedonic well-being3, social well-being, depression, anxiety, and loneliness. The headline was that overall, social media use showed little association with these outcomes. Yet the study did find significant correlations with anxiety (r = .13) and depression (r = .12).

Hancock et al. also provide an analysis restricted to longitudinal studies, which is ostensibly why Odgers cited the study. But here, complications surface.

For these longitudinal studies, Hancock did not report results for depression specifically. Instead, the authors combined outcomes into two broad categories: “psychological well-being” (eudaimonic, hedonic, social) and “psychological distress” (depression, anxiety, loneliness). Between these two, “psychological distress” is more relevant to our hypotheses. When they analyzed the psychological distress category, they found no evidence of an effect in either direction. They wrote:

“For psychological distress, neither the effect size of Use → Well-being (r = -.04, 95% CI = [-.14, .05], p = .28) nor the effect size of Well-being → Use was significantly different from zero (r = .00, 95% CI = [-.10, .11], p = .99).”

In other words, the social media use → psychological distress estimate was -0.04 (CI: [-0.14, 0.05]), while the psychological distress → social media use estimate was 0.00 (CI: [-0.10, 0.11]). Therefore, taken at face value, this study cannot be used as evidence for either forward or reverse predictability, and instead corresponds to evidence of no relationship between social media use and mental health.

Additionally, undermining the study’s relevance to the question of social media’s effect on depression in adolescents, these studies did not focus solely on our population of interest — adolescents. It’s worth noting, however, that in their analysis of the larger set of cross-sectional studies, they report that correlations were larger for the minority of studies that examined adolescents, compared to young adults.

Taken together, these two aspects make it clear that these results are not relevant to the specific hypotheses about the effect of social media use on internalizing disorders in adolescents.

Study 3. Heffer et al. 2019

Of the three papers we’ve covered here, Heffer et al. 2019 is the only one that seems to provide reasonable support for the reverse predictability hypothesis put forth by Odgers. Heffer and colleagues studied 597 Canadian elementary school students at two points in time, one year apart. They measured time spent on social media and depressive symptoms, then applied an autoregressive cross-lagged path model to test whether one predicted the other. For girls, they reported that depression predicted later social media use, while social media did not predict later depression. For boys, neither pathway reached significance (though the social media → depression pathway came very close). However, there are two important caveats to note.

First, while the paper reports no significant social media → depression effect for boys, that is only because the confidence interval for the relevant estimate exactly includes 0.00. Moreover, the magnitude of the point estimate for social media → depression for boys (0.145, 95% CI [0.000, 0.288]) was larger than that for depression → social media for girls (0.131, 95% CI [0.026, 0.236]). Given these observations, it seems unreasonable to conclude, based on the cutoff point of p < 0.05, that this result provides no evidence for forward predictability. The result would have been statistically significant for any slightly higher p-value threshold, and the magnitude of the estimate for forward predictability for boys was larger than that for reverse predictability for girls.

Second, when considering an alternative and simpler measure of predictability, social media use at T1 did predict future depression for both boys and girls. Table S.1, from the appendix, shows the correlations between social media at T1 and depression at T2; they are 0.251 for girls and 0.264 for boys, and they are each statistically significant at the 0.001 level. Furthermore, the correlations did not decline over time — they were as strong as the contemporaneous correlations between social media use and depression at T1. For boys, the correlation actually increased: from 0.178 between social media use at T1 and depression at T1 to 0.264 between social media use at T1 and depression at T2 (one year later). In other words, social media use among boys at T1 had higher correlation with depression at T2 one year later than with contemporaneous depression at T1.

Of these three studies, this is the best evidence for the reverse predictability hypothesis. At the same time, the findings also lend some support to the forward predictability hypothesis. The results may actually point toward a bidirectional relationship between social media use and depression, which would still suggest that social media poses risks to adolescent mental health.

To summarize our analysis in this section:

We conclude that these three studies do not provide evidence for Odgers’ “reverse predictability” hypothesis, and that they should not be cited as evidence against the forward predictability hypothesis put forth in TAG. In summary:

Puukko et al. (2020): Did not measure time spent on social media, focusing instead on the healthier forms of digital media communication.

Hancock et al. (2022): Blended together social media use measures, outcomes and age groups, and found no evidence for reverse predictability. The psychological distress → social media estimate was zero.

Heffer et al. (2019): Of these three studies, this is the best evidence for the reverse predictability hypothesis, though only for girls. Interestingly, it also provides some evidence for the forward predictability hypothesis. Indeed, it may support a reciprocal relationship, which would still imply that social media use is a source of harm to adolescents.

Overall, these studies do not support the conclusion that the relationship between social media and mental health runs primarily in the reverse direction.

Forward Predictability

In this section, we present three studies that directly addressed our central question and illustrate forward predictability, showing that more time on social media predicts higher levels of depression or internalizing symptoms later. These studies were not cited by Odgers, but provide relevant evidence for evaluating forward and reverse predictability. The first (Riehm et al., 2019) is a widely-recognized study in this area, while the latter two are recent papers (both 2025) using newer data and methods.

Study 1. Riehm et al. (2019)

Riehm and colleagues conducted a cohort study of 6,595 U.S. adolescents, measuring time spent on social media and later internalizing problems. The study was cited by the former U.S. Surgeon General in his 2023 advisory on social media and youth mental health:

“A longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adolescents aged 12–15 (n=6,595) that adjusted for baseline mental health status found that adolescents who spent more than 3 hours per day on social media faced double the risk of experiencing poor mental health outcomes including symptoms of depression and anxiety.” [Emphasis added]

This study, published in 2019, is a well known, high-quality counterexample to assertions that longitudinal studies only show evidence in support of reverse predictability. With respect to internalizing disorders, they found that use of social media for more than three hours per day, compared with no use, was significantly associated with internalizing problems alone. They estimated a risk ratio of 1.60 (95% CI, [1.11, 2.31]). Put differently, heavy social media use at one time was significantly associated with a 60% increase in internalizing disorders at a later time.

This study is particularly valuable because the authors used a different design from the other studies we consider. Rather than try to simultaneously estimate the effect of social media use at T1 on mental health at T2 and vice versa, they consider a staggered design and estimate the effect of social media use at T2 on mental health at T3, while controlling for mental health at T1. Their approach “mitigates the possibility that reverse causality explains these findings,” in the words of the authors. While this approach does not account for possible confounding of mental health at T24, it is a very helpful complementary approach to the other designs and statistical models considered in the other studies we’ve reviewed.

Study 2. Nagata et al. 2025

The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study is a long-term U.S. cohort study tracking more than 10,000 children beginning in 2015–16, when participants were ages 9–10. This high-quality dataset is particularly valuable because it measures both time spent on social media and depression symptoms, though (for now) it focuses primarily on late childhood and early adolescence (ages 9-13). Importantly, the two studies we review here used random-intercept cross-lagged panel models, an improved version of the cross-lagged models used in studies typically cited as evidence of reverse predictability, such as Heffer et al. 2019. Hence, these two studies can give perhaps the best apples-to-apples evidence, compared to the Heffer et al. study we reviewed above.

With the ABCD dataset, Nagata et al. 2025 examined the relationship between social media use and depression. They report:

“within-person increases in social media use above the person-level mean were associated with elevated depressive symptoms from year 1 to year 2 (β, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.01-0.12; P = .01) and from year 2 to year 3 (β, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.04-0.14; P < .001), whereas depressive symptoms were not associated with subsequent social media use at any interval.” [Emphasis added]5

In other words, more social media use predicted later depression, but depression did not predict later social media use. According to an effect size guideline designed for these types of measures (Orth et al. 2024), this is a “medium-sized” effect size.

Study 3. Grund & Luciana 2025

Using the same ABCD dataset, Grund & Luciana examined whether earlier psychological characteristics (impulsivity, motivation, psychopathology, and cognitive ability) at age 8-11 (mean: 9.5, SD: 0.5) predicted future screen time, including social media use, at ages 11-17 (mean: 13.6, SD: 0.7). Most relevant to this review, they estimated a relationship between internalizing psychopathology → social media use, where internalizing psychopathology is a composite score of depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints subscores.

Crucially, they found that internalizing psychopathology was not associated with later social media use (β, 0.01; 95% CI, -0.01-0.03; p < 0.387). This is evidence against the reverse predictability hypothesis.

By contrast, they found that urgency, reward sensitivity, and externalizing symptoms were associated with more future time on social media, while general cognitive ability and learning/memory were associated with less future time.

Conclusion

Based on the six studies we’ve reviewed in this post, we draw two conclusions:

Three studies commonly cited as evidence of reverse predictability (Puukko et al. 2020, Heffer et al. 2019, and Hancock et al. 2022) do not provide strong evidence that depression is associated with increased subsequent social media use, nor do they provide much evidence against the claim that social media use predicts subsequent poor mental health.

Three other high-quality studies (Riehm et al. 2019, Nagata et al. 2025, and Grund & Luciana 2025), using two different datasets and designs, found that earlier social media use predicted subsequent depression and internalizing disorders. Moreover, they failed to find evidence of the reverse relationship: that poor mental health predicted subsequent social media use.

The public debate that initially inspired this post centered on whether longitudinal evidence supported forward or reverse predictability. Our review suggests that the three studies commonly cited as evidence for reverse predictability have significant limitations and do not strongly support that hypothesis. Meanwhile, multiple high-quality studies using different datasets and methods provide evidence for forward predictability. The longitudinal evidence reviewed here does not support the conclusion that the relationship runs primarily in the reverse direction.

Nonetheless, continued research into the relationship between social media use and internalizing disorders in adolescents is needed. While this post discusses only six related studies, many more exist and we plan to collate a better and more formal review of the full literature.

Some of the most robust cross-sectional evidence on this question concerns depression, so our analysis in this essay will focus on that outcome. We note that in her Nature review, Odgers seems to use “depression” and “mental health problems” interchangeably. We recognize that there are many different aspects of mental health and well-being, including internalizing symptoms, stress, life satisfaction, and subjective mood. It is important to study each of these (and their relationship with technology) separately.

Another important point: There are many ways researchers measure “social media use” in practice — time spent per day; frequency (how often) measures; active and passive use; whether someone is a daily user; intensity of use, and dependency. Each of these measures may be useful for investigating different questions about the nature of social media use. However, the claim made in The Anxious Generation was primarily about the dangers of heavy use (many hours a day, which now characterizes mostadolescents).

In the Nature review, Odgers only cites Heffer et al. 2019.

According to the authors: “Eudaimonic well-being involves cognitive evaluations of one’s life… Eudaimonic wellbeing constructs include life satisfaction and self-esteem,” and “Hedonic well-being focuses on the presence of positive and the absence of negative emotionality… Whether or not someone is feeling overall pleasure or displeasure would be categorized as hedonic well-being.”

See Kreski and Keyes (2020) for further details.

The age groups referenced above are ages 10-11 (year 1), 11-12 (year 2), and 12-13 (year 3), so this study is focused on late childhood and early adolescence.

I'm very encouraged by your work. At the same time, this topic reminds me of debates in the nutrition world about the correct definition of ultraprocessed foods. Let the scientists work it out, but in the meantime, the rest of us can use our common sense to limit our exposure to these modern hazards (UPF's and invasive tech), replacing them with real food, in person human connection, etc, etc. 🙏

We all appreciate the technical deep dive and links to actual studies; as lay people, it is often difficult to support these arguments with people who aren't engaged with children regularly. There is no question in my mind that harm is being visited on children via many different avenues, and social media is only part of it. The real culprit behind all this is advertising, which has always been a subset of the greed of the 20th-21st century, a subset of the petrodollar and its usurious nature.