Changes in Parents’ Mental Health Did Not Drive the Adolescent Mental Health Crisis

Jean Twenge rebuts another skeptical argument

Intro from Jon Haidt and Zach Rausch:

We love it when critics of our work propose alternative explanations for the youth mental health crisis. Zach and I keep a whole collaborative review doc full of such theories, which we invite you to view and comment on.

One alternative that some critics have recently proposed is that we shouldn’t be looking to the kids to find the source of the mental health crisis; instead, we should be looking to the parents. These critics argue that because parent-aged adults have higher rates of suicide than teens and those rates have been rising, it might be that parents got more depressed and suicidal in the 2010s, and that has—in turn—influenced their children.

Jean Twenge has been masterful at testing these alternative theories and showing that all of them contradict the timing, the demographics, or the international dimension of the epidemic. (See Jean’s post: Here are 13 Other Explanations for the Adolescent Mental Health Crisis. None of Them Work.) In fact, Jean’s latest post here at After Babel showed that Suicide Rates Are Now Higher Among Young Adults Than the Middle-Aged.

In today’s cross-post from her Substack, Generation Tech, Jean shows that the “parents first” hypothesis is out of sync with the cross-generational data from the 2010s. Jean’s post is important because—as far as we know—she is the first to use data that distinguishes between parents and non-parents. (This is not possible to do with suicide rate data). Her graphs below tell a powerful story: something happened to the teens, not to the parents, in the 2010s. She also shows that if anything happened to the adults, it seems to have mostly happened to the non-parents.

Please, send us more alternative explanations. If you have one, put it in the comments at the end.1

— Jon and Zach

Several critics of the idea that Gen Z is suffering a mental health crisis have argued that attention should instead be focused on the middle-aged, particularly middle-aged parents. This is the group experiencing high levels of mental health issues, they say.

If so, that could be why teen depression has increased – not smartphones and social media, but depressed and distressed parents. Past research has indeed found that when more parents experience mental distress, so do their children.

In an article headlined “The kids are all right, but the adults are struggling,” sociologist Mike Males wrote, “It’s not the youth who are creating the crisis. It’s their parents’ generation.” He then went next-level, declaring that “College counselors likewise invented a ‘student mental health crisis’ (despite the fact that undergraduate violence and suicide rates are unusually low) to win more funding.”

Psychologist Chris Ferguson recently argued that discussion is too centered on “Gen Z (e.g. ‘…a generation in crisis…’), ignoring that mental health issues are much worse among their parents.” Elsewhere, he contended that the rise in youth depression is not due to smartphones and social media but to their parents’ mental health issues: “It’s intergenerational. Kids are in pain because their families are in pain.”

These statements offer up a testable hypothesis: Are mental health issues worse among the middle-aged parents of teens and young adults, or among teens and young adults themselves? And have mental health issues increased among parents? To my knowledge, no one else has examined mental health trends specifically among parents in the large national datasets.

My previous post showed that the suicide rate for U.S. adults in their 20s is now higher than that for middle-aged adults, reversing a long-standing trend. That happened partially because suicide rates have increased so much among young people. So in terms of the suicide rate, a “hard” statistic uninfluenced by self-report bias, the trends for young adults are definitely worse than for the middle-aged.

In suicide data, however, there is no way of separating the data by parents vs. non-parents. But we can examine depression, suicidal thoughts, and mental distress among parents with children 17 or under at home in the nationally representative National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH takes a cross-section of the whole population, not just those who seek help from doctors or therapists; thus, trends cannot be due to over-diagnosis or more willingness to get professional help.

We’ll first consider rates of major depressive episode (clinical-level depression according to the DSM criteria). By that indicator, teens are doing much worse than middle-aged adults with children at home (see Figure 1). In recent years, 1 in 5 teens suffered major depression, compared to 1 in 14 of parents ages 35 to 64. Depression rates among parents have barely budged, while rates for teens have more than doubled. The two groups had fairly similar depression rates in the late 2000s, but that began to change after 2011.

Figure 1. Percent suffering from a major depressive episode in the last 12 months, U.S. adolescents 12-17 and 35-64 year olds with and without minor children at home, 2008-2022. Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Analyzed and graphed by Jean Twenge for the Generation Tech Substack. NOTE: Due to privacy concerns, NS-DUH reports age in groups rather than individual years. 35- to 64-year-olds is the age grouping overlapping the most with those most likely to have adolescent children (roughly 35-59).

Not only that, but middle-aged adults with children at home are actually less likely to experience minor depression than middle-aged adults without children at home. And, in sharp contrast to teens, neither group shows an increase in depression since 2008.

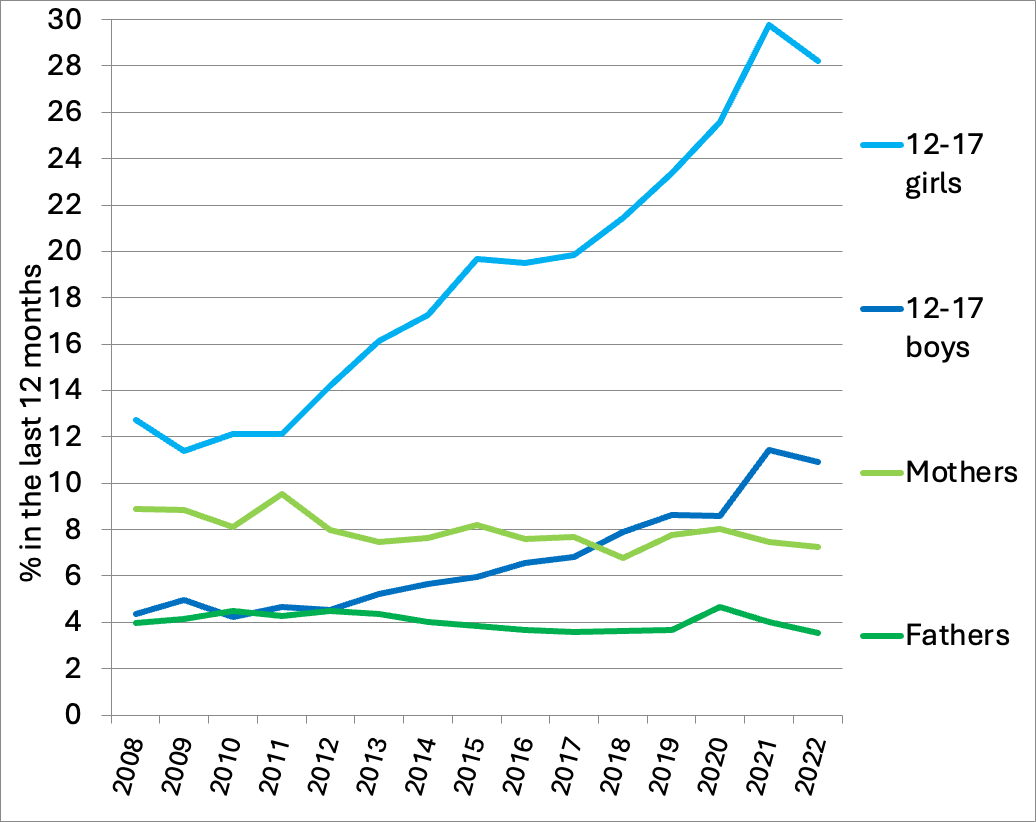

Breaking teens vs. parents down by gender shows an even starker pattern, with an enormous increase in depression among teen girls, a smaller (absolute) rise among teen boys, and little change among mothers or fathers with children still at home (see Figure 2). Major depression among mothers actually declined slightly (from 9.6% to 7.3%) between 2011 and 2022.

Figure 2. Percent suffering from a major depressive episode in the last 12 months, U.S. adolescents 12-17 and parents 35-64, by gender, 2008-2022. Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Analyzed and graphed by Jean Twenge for the Generation Tech Substack. NOTE: Mothers and fathers are those ages 35-64 with children 17 or under living in their household.

Depression rates are now higher among teen boys than among middle-aged mothers, a complete reversal from the usual pattern of females being more likely to suffer from depression than males.

What about even more serious issues, such as thinking about suicide? NSDUH does not ask that question of teens, but it does ask it of young adults. Here, too, rates for parents are much lower than for young adults, and the rates for young adults have more than doubled (see Figure 3). By the 2020s, 1 in 8 young adults had considered taking their own life in the previous year. For parents, it was less than 1 in 30, and lower for those in the same age range without children at home.

Figure 3. Percent having suicidal thoughts in the last 12 months, U.S. young adults 18-25 and 35-64 year olds with and without minor children at home, 2008-2022. Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Analyzed and graphed by Jean Twenge for the Generation Tech Substack.

When broken down by gender, there is very little change among either mothers or fathers, while the number of young adult men and women having suicidal thoughts doubled (see Figure 4). The highest rates of suicidal ideation are among young women, where nearly 1 out of 6 thought about taking their own lives in the last year.

Figure 4. Percent having suicidal thoughts in the last 12 months, U.S. young adults 18-25 and parents 35-64, by gender, 2008-2022. Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Analyzed and graphed by Jean Twenge for the Generation Tech Substack.

Major depression and suicidal thoughts are very serious issues. Perhaps parents are less likely to have these issues because they are parents; for example, they may not think about suicide because they can’t imagine leaving their kids on their own. Thus, it might be good to examine less serious but still troubling symptoms of mental health issues, such as mental distress. NSDUH includes the Kessler-6, a 6-question measure of mental distress including questions about nervousness, hopelessness, and feeling everything is an effort. Even if parents aren’t considering taking their own lives, they may certainly be more susceptible to mental distress like this.

Except they aren’t. Serious mental distress is much higher among young adults, where it has more than doubled since the early 2010s. Mental distress among parents is very low and has ticked up only slightly, from 4% in the early 2010s to about 5% in the 2020s (see Figure 5). Mental distress increased slightly 2019-2022 among middle-aged adults without children at home, but not among those with children.

Figure 5. Percentage with serious mental distress, U.S. young adults (18-25) and 35-64 year olds with and without minor children at home, 2008-2022. Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Analyzed and graphed by Jean Twenge for the Generation Tech Substack. NOTE: Scores on the Kessler-6 range from 0 to 24. A score of 13 or higher is considered serious mental distress.

Similar to the other mental health indicators, serious mental distress is highest among young women and lowest among mothers and fathers (see Figure 6). There are large increases among young adults since 2011 and only slight change among middle-aged parents.

Figure 6. Percentage with serious mental distress, U.S. young adults (18-25) and parents (35-64), by gender, 2008-2022. Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Analyzed and graphed by Jean Twenge for the Generation Tech Substack.

Since NSDUH doesn’t allow precision in examining age groups and doesn’t include a consistent measure of child age, it admittedly may be including some people in the parent group who aren’t parents with adolescents. To do that, we can turn to the BRFSS, administered by the CDC, which has age in more precise groupings and – at least in 2021-22 – an indicator of child age.

Middle-aged people with teen children (the 40-55 age group) have fewer days of poor mental health than those in the same age group without minor children at home (see Figure 7). Those with tween children (the 35-49 age group) also have fewer days of poor mental health than others in the age bracket. But who has the highest number of poor mental health days? The youngest adults, those ages 18 to 22. Other analyses of this dataset show a marked increase in poor mental health days among young adults in the last decade.

Figure 7. Days per month in poor mental health, U.S. adults, by children in household and age, 2021-2022. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Analyzed and graphed by Jean Twenge for the Generation Tech Substack. NOTE: Graph shows parents with children ages 10 to 14 for those ages 35-49 and parents with children 15-17 for those ages 40-55, to capture the most common ages for parents with tween and teen children, respectively, and compare them to those without minor children at home in the same age range.

Thus, across five metrics — suicide, major depression, suicidal thoughts, mental distress, and days in poor mental health — young people are suffering more than the middle-aged, and that suffering has increased considerably since 2011. None of this is consistent with the narrative that parents’ mental health issues or intergenerational family dynamics are the cause of the mental health crisis among Gen Z. Instead, it must be something happening to the generation themselves.

There happens to be something else that shows the pattern of larger change among teens and young adults and less among older people: Face-to-face social interaction, which has decreased by far the most among the young (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Minutes per day socializing with others in person, U.S. teens and adults 15 years of age and older, 2003-2022. Source: American Time Use Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Analyzed and graphed by Jean Twenge for the Generation Tech Substack. (NOTE: 2020 data is excluded.)

And what has replaced face-to-face socializing? More online communication, which is not as good for mental health. It should not considered radical to suggest this enormous shift might have an impact on rates of depression.

It should also not be so easy to declare that we’re focusing on the wrong age group when the data so clearly point toward an overwhelming crisis among teens and young adults, and not among middle-aged parents.

These findings are yet another reason why the rise in teen depression is so remarkable: It happened at a time when violent crime, teen pregnancy, problematic alcohol use, family dysfunction, unemployment, and now parental depression are at historically low or at least stable rates. So much is going right for young people these days, including the mental health of their parents. Yet they are still much more depressed than teens in the 2000s, likely because they spent more time online, less time with friends in person, and less time sleeping. That explanation fits the data much better than declaring an epidemic of depression among parents that, by the best data we have, doesn’t exist.

One additional explanation we are investigating is “abandonment deaths,” an interesting argument made by David Stein. Another is the role of progressive ideologies that swept through the Anglos in the early 2010s—for an overview of our current response to that, read this post.). Zach is also working on a new Google Doc (it is still in preliminary stages) that is looking specifically at what has been happening to adults—more broadly—since the early 2010s.

I think there needs to be more analysis of the *content* of what teens are looking at on social media, how content has changed over time since teens have had widespread social media use, and how the ideas of that content has spread beyond social media and into broader culture so that even kids who are not on social media or are light users of it are affected by these ideas. I feel like Haidt puts too much weight on Instagram causing girls to be insecure about their looks and waiting for likes and comments from their friends (photoshopped magazines, billboards, and celebrity photos were around and blamed for soaring numbers of eating disorders and insecurities long before 2012). They need to look at the ideas that are being constantly repeated in the memes, reels, and TikToks. For example, that everything they feel is a symptom of anxiety or depression which is a central theme even in what is supposed to be funny or irreverent content. Also that everything they do is somehow political or about their identity, that their words, their opinions, even the content they consume or post can have literally life or death effects. I feel like they discuss these issues (like the idea of reverse CBT in The Coddling), but they aren't making the connections with that this is the content the kids are seeing more and more of on social media. For example, if you take two teen girls who spend four hours a day on instagram, that's too much time that will negatively effect both, but if one is spending that four hours watching funny videos about pandas, recipe videos because she has a baking hobby, softball videos because she plays in a weekend rec league, and other various light non-political videos, I predict she has a lot better mental health than another girl who spends that same amount of time watching videos about politics and identity that keep her constantly on edge, looking for threats and focused on problems combined with videos constantly talking about their anxiety and low-key depression.

I very much appreciate Jean Twenge taking up this complex topic that we all should have been on top of 20 years ago, when parent-age suicide and overdose rates started rising/skyrocketing, and Gen Z was in diapers. Now we have multiple, full-blown crises.

First, 20-agers are not the most suicidal. The short-lived 2020-21 spike in younger-age suicides accompanying the COVID pandemic has since abated. Both 2022 and 2023 CDC figures, with very few deaths remaining to be added, show middle-agers have returned to being the most likely to commit suicide. Teens’ and age 20-29’s suicide and overdose rates fell sharply in 2022, while middle-aged rates rose. In 2022 and 2023, age 20-24’s suicide rate ranked below every older age group 25-64, and teens' rates were the lowest of all.

Second, Twenge relies heavily on survey self-reports of mental health (depressive episodes and suicidal thoughts) that are amply contradicted by real-world outcomes. Mental health issues such as depression, suicidal thoughts, and addiction are deeply stigmatized in American society as moral weaknesses. That middle-agers SAY they’re always doing fine is not relevant.

Tragic outcomes are. Even selectively picking the post-2010 time period during which teens had their biggest increases in self-destructive deaths (suicides and overdoses), grownups of age to be their parents were and are doing far worse.

I randomize this comparison by using the ages of the Surgeon General and local substackers (I’m the oldest) to contrast with teens and young adults. Using standardized deaths from self-inflicted suicides and overdoses per 100,000 population from 2010 to 2022, the kids aren’t the problem:

Girl, age 14: up 3.0 annual deaths to 4.7 per 100,000 population in 2022.

Girl age 16: up 3.6 annual deaths to 7.5 in 2022

Boy age 18: up 7.7 annual deaths to 32.2 in 2022

Man, age 46: up 66.1 annual deaths to 101.5 in 2022

Woman, age 52: up 16.1 annual deaths to 42.1 in 2022

Man, age 60: up 49.4 annual deaths to 106.2 in 2022

Man, age 73: up 17.8 annual deaths to 43.8 in 2022

Note that father-age men, 46, suffered an increase in self-inflicted deaths 18.3 times faster to a level 13.5 times higher than did 16-year-old girls, and even worse trends and levels compared to middle-school girls. Overall, from 2010 through 2022, a record 798,000 middle-agers died from self-inflicted suicides and overdoses, equivalent to the entire population of San Francisco gone. As Gen Z grew up, middle-aged suicide/overdose deaths soared from 23,228 (2000) to 40,730 (2010) to 98,470 (2022).

Unlike misleading percent changes applied to wildly differing numbers, this standardized comparison reflects what families actually experience. Teens left behind after the death of a parent, relative, teacher, coach, etc., would find that depressing, but we don’t ask teens what’s making them unhappy.

Twenge's points suggest a fascinating question, though. How is it that teens (especially girls) report more depression and suicidal thoughts than middle-agers, yet teens (especially girls) have such strikingly low rates of suicide and self-destruction in real life?

It isn’t meds. Middle-agers are much more likely to take anti-depressants than teens or young adults (yet, middle-agers claim they’re less depressed?). It isn’t economics; midlifers are America’s wealthiest age, able to afford mental health care. Further, aren’t middle-agers “developed brains” supposed to make more reasoned decisions than supposedly impulsive “teenage brains”?

I argue one reason for teens’ (especially girls’) extraordinarily low rates of manifest self-destruction – not likely to sit well here! – may be teens’ greater use of social media. That argument results from yet another paradox no one mentions.

According to the CDC survey, teen girls who use screens 5+ hours/day are more likely to report frequently poor mental health (47%) than teens who use screens <1 hour/day (30%), as well as sadness (50% vs 34%), and considering suicide (31% vs 23%). I see those comparisons cited a lot.

However, no one mentions that those same frequently-onscreen teen girls on the same survey then turn around and report being LESS likely to actually attempt suicide (15% vs 19%) and to self-harm (3% vs 7%), as well to try hard drugs, be violence victims, etc., compared to rarely on-screen girls. How can screen time be both more depressing and less suicide/harm inducing?

Put another way, what intervenes between depression and actual suicide attempt/completed suicide to strongly protect girls from actual harm? One clue is that girls are much more likely to suffer parental abuses than boys (62% vs 48%); frequently on-screen girls are 88% more likely than rarely on-screen girls to be abused by parents/grownups; and parent-abused girls are 8 times more likely to attempt suicide (32% vs 3%) and 27 times more likely to self-harm (10% vs 0.3%) than non-abused girls (again: this is the population we’re worried about). Do we then conclude that girls being online somehow provokes parents to violent and/or emotional abuses?

Or, do we look at these as reverse correlations: that abused/depressed girls are more likely to log more screen time than their non-abused counterparts to connect with others who reduce their suicide, self-harm, and other risks?

Finally, Twenge raises another good issue elsewhere: economically advantaged teens report nearly as high depression levels as disadvantaged teens, yet suicide/overdose “deaths of destruction” rates and increases are much worse among poorer adults. However, teen deaths show a similar pattern. The highest levels and worst trends in teen suicides/overdoses by far are among rural White teens in conservative (Republican) states compared to White or diverse teens in Democratic cities, with other populations in between. That is, teens in liberal areas may report more depression, but they are much less likely to actually kill themselves compared to teens in conservative areas.

This suggests yet another disconnect between teens’ amorphous attitudes like depression or sadness (whose meaning we can’t interpret) versus overt suicide attempts and self-harm, along with real-life suicides and self-harm cases (all actual behaviors). A teen depressed because of global warming, Gaza, her dog dying, or getting beaten by mom’s boyfriend requires very different approaches than one depressed because of social-media snarks, or chemical imbalance.

We can nitpick flaws in each other’s studies and surveys, but what we really need is large, comprehensive surveys that ask teens more detailed questions about how a variety of parental issues – abusive behaviors, drug/alcohol abuse, suicidality, unemployment, arrest (rates are now higher among 40-agers than high-schoolers!), incarceration, etc. – as well as political issues affect teens’ own mental health and behaviors. The 2021 CDC survey showing parents’ abuses and job losses were much more important drivers of teens’ depression and suicidality than screen time (including TV time) hint at a much larger problem.