Academic Pressure Cannot Explain the Mental Illness Epidemic

It’s not the homework. It’s the phones.

Today we have our first guest post on the After Babel substack from my research partner Jean Twenge. Jean was among the very first to sound the alarm about the mental illness epidemic that began around 2012. Her 2017 Atlantic article was given this title by the editors: HAVE SMARTPHONES DESTROYED A GENERATION? Other psychologists criticized her for fomenting a moral panic on what looked like 2 or 3 years of data showing a trend on some but not all mental health variables. But now we can see that she was absolutely right. That article was drawn from her book iGen, which stands to this day as the definitive account of what is now called Gen Z.

When Greg Lukianoff and I published our own book on Gen Z, The Coddling of the American Mind, we drew heavily on Jean’s work. After our book came out, I asked Jean to join me on the Collaborative Review docs that are the empirical foundations of the After Babel Substack.

Jean has a book coming out on April 25: Generations: The Real Differences Between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents―and What They Mean for America's Future. If you like what you read here, please pre-order it.

— Jon Haidt

When I first started to see the uptick in teen depression in the large survey datasets I work with, I had no idea what might have caused it. The uptick began around 2012 or 2013 and didn’t align with economic trends.1 It was difficult to think of an event that occurred in the early 2010s and would cause depression to keep rising year after year. The rise in teen depression was – to me and everyone else – a mystery.

But as I considered what else was changing around that time, it started to make sense: 2012 was the first year the majority of Americans owned a smartphone. It was also when daily social media use among teens moved from ~50% — thus, fairly optional —to ~75%, where if you didn’t use it, you were left out. And given the mounting empirical evidence (which Jon documented in a previous post) showing links between social media and depression (as well as the decline in in-person social gatherings among teens), the rise of these technologies is the most likely cause of the increase in teen depression. The impact of technological change on teen depression was the central thesis of the core chapters of my 2017 book, iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy – and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood. My upcoming book, Generations, updates the evidence in the Gen Z chapter.

One of the primary criticisms of the smartphone/social media hypothesis has always been this: How do you know something else didn’t cause the increase in teen depression?

After the CDC’s recent report showing shocking increases in mental health issues among adolescents, especially girls, there has been renewed attention to why teen depression has increased so much since 2012. Although much of this discussion has focused on social media, another explanation has recently become more widely touted: Increasing academic pressure.

In The Atlantic, Derek Thompson argued, “A culture of obsessive student achievement and long schoolwork hours can make kids depressed.” He quotes psychologist Laurence Steinberg of Temple University, who says, “I have for years thought that one of the main causes of the increase in adolescent depression was an increase in school pressure.” Thompson also cites research suggesting that “rich teens in high-achieving schools” are the most depressed. Delilah Brumer, a high school senior, talked to her peers for a piece published on Yahoo! News. Many mentioned feeling stress around grades, a point she backs up with a Pew Center poll finding that 61% of 13- to 17-year-olds say they feel a lot of pressure to get good grades. She argues that the college admissions process has become increasingly stressful. Taylor Lorenz of the Washington Post made a similar argument on Twitter: “I really disagree this is all smartphones and social media. For instance, kids now have more homework than ever.”

The good thing about an argument like this is we can test it. Three questions come to mind based on these recent pieces and observations:

Do Gen Z teens spend more time on homework than previous generations at the same age? Did homework time increase concurrently with teen depression?

Do Gen Z teens report feeling more academic pressure than previous generations at the same age? Did feelings of academic pressure increase concurrently with teen depression?

Are higher-achieving teens — those fighting for good grades and aiming for college — more likely to be depressed than lower-achieving teens? And has depression increased more sharply among high-achieving teens compared to less academically oriented teens?

The Monitoring the Future study of U.S. teens collects a nationally representative sample in schools every year and has data that can answer all three of those questions. The answers don’t look good for the academic pressure hypothesis.

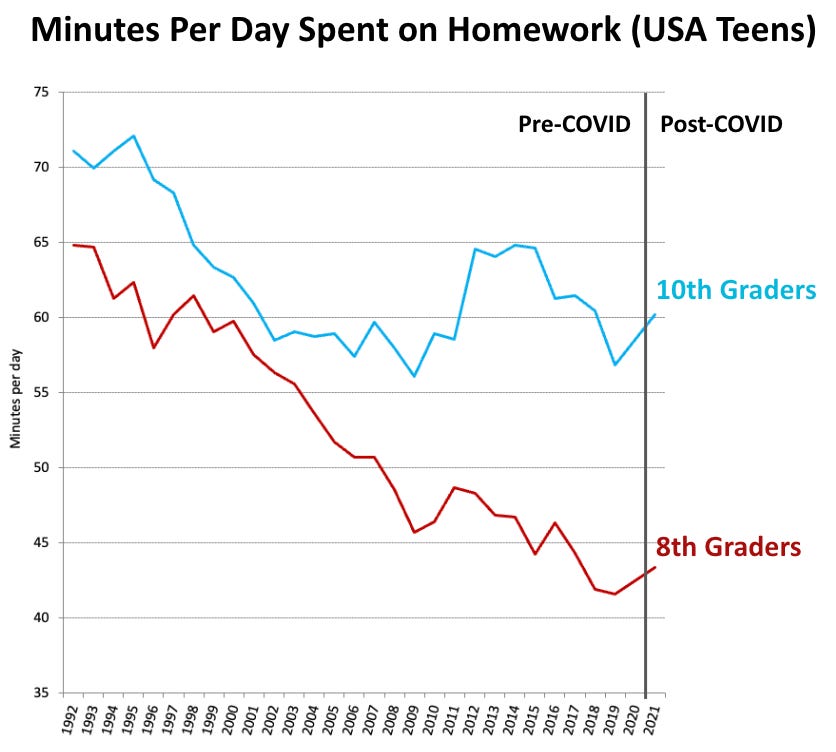

Question 1: Is Homework Time Increasing?

Monitoring the Future asks teens how many hours they spend on their homework in an average week. Below are the average responses, converted to minutes per day, for 8th and 10th graders from 1991 to 2021:

Figure 1. Minutes per day spent on homework, Monitoring the Future Survey.2 The 2020 data were collected in early 2020, just before COVID-19 shut schools down.

For 8th graders, the trendline is consistently down — Gen Z 8th graders spend less time doing homework than Gen X and Millennial teens did, though the difference is small (about 10 minutes less a day). Notably, 8th graders are 13 and 14 years old, and 12- to 14-year-olds are the group with the largest increases in depression, self-harm, and suicide (larger than the increases among 17- and 18-year-olds, percentage-wise, which in itself is an argument against the “it’s the college applications” idea). Gen Z 10th graders — in a crucial year for the college-application GPA — also spend about 10 minutes a day less on homework than Gen X 10th graders did in the early 1990s. However, the decline is less consistent: homework time rose in the early 2010s but fell again after 2015.

So, teens do not have “more homework than ever.” In fact, they have less.

It's also worth noting that, on average, teens spend only about an hour a day on homework. For context, the 2021 Common Sense Media report found that teens spent an average of 9 hours a day on entertainment media.

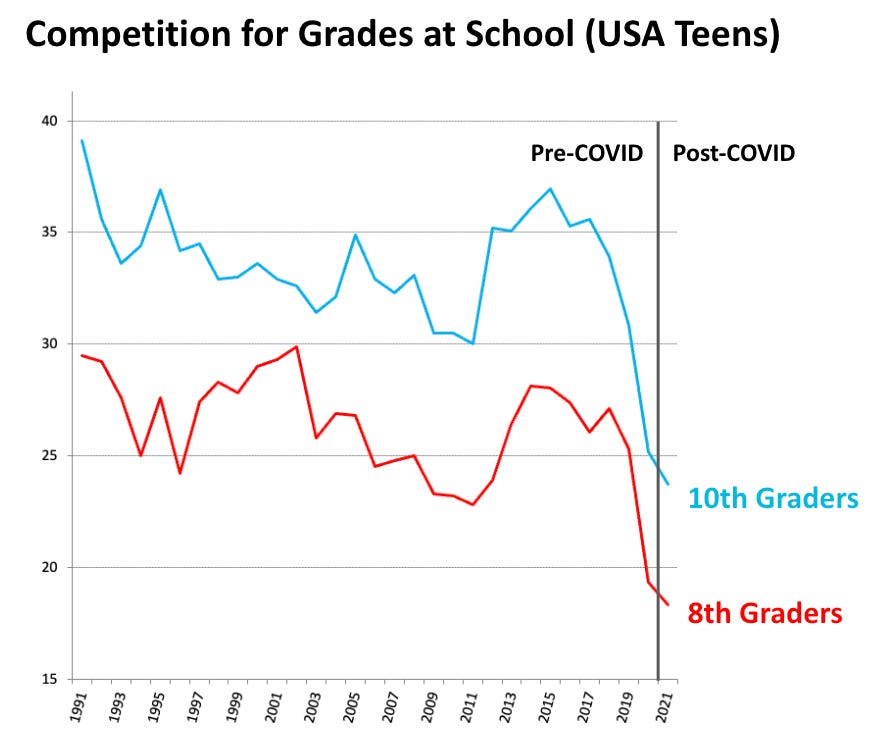

Question 2: Is Perceived Academic Pressure Increasing?

Of course, academic pressure isn’t just about homework time. The overall atmosphere of a school around grades is also important – a pressure-cooker environment is often stressful. Fortunately, the Monitoring the Future survey asked teens a question that is a decent measure of this type of academic pressure: “How much competition for grades is there among students at your school?”

The graph below shows the percentage of teens who say there is “quite a bit” or “a great deal” of competition for grades.

Figure 2. Percent reporting “quite a lot” or “a great deal” of competition for grades at their school, Monitoring the Future Survey. Although the overall trend is down, there was an uptick around 2012 for all grades, but then the numbers fell again a few years later. The 2020 data were collected in early 2020, just before COVID-19 shut schools down. The recent sharp downturn in agreement began before COVID-19.

Similar to the pattern for homework time, Gen Z teens report less competition for grades at their schools than Gen X and Millennial teens did. In fact, in recent years – the same years with all-time high levels of depression – teens reported all-time low levels of academic pressure at their schools. The 2019 Pew poll showing teens felt a lot of pressure around grades might be true, but that pressure may have been the same or worse in previous generations. If there has been a steady increase in academic pressure, it’s not showing up when teens are asked about it directly.

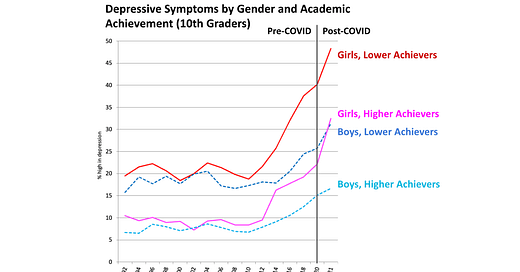

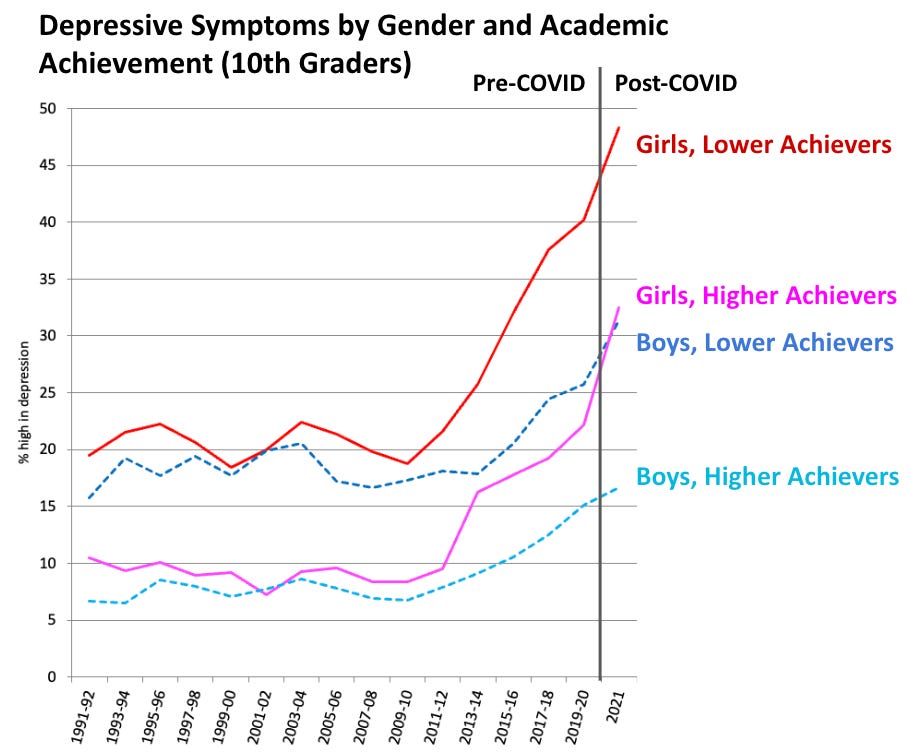

Question 3: Did depression rise more among higher achievers than lower achievers

A common theme in the recent observations about academic pressure is the stress around college admissions: college is harder to get into, teens spend countless hours fighting for As, writing essays, and polishing their applications, and the stress leads to depression. Is this true?

First, it’s important to remember that most teens do not apply to selective colleges. Only about half of high school seniors (in Monitoring the Future) plan to attend a four-year college, and most will go to colleges that admit the majority of students who apply. A very small percentage of teens engage in the “rat race” for Ivy League and Ivy-adjacent schools, not nearly enough to significantly impact the national depression numbers.

Still, it’s worth examining these questions: Who is more depressed, teens who plan to go to college and so must fight for good grades or teens with lower ambitions and less stellar records? And has depression risen the most among high achievers, as one would expect if academic pressure were the cause of the rise?

About 1 out of 4 10th graders is what we might describe as a high achiever: They have an A or A- grade point average and plan to attend a four-year college. So, by the academic pressure theory, this is the group we should be worried about – they are the ones who should be the most stressed out about grades and college.

Again, we can use Monitoring the Future data to test this hypothesis. As it turns out, the high achievers are actually less likely to be depressed than the lower achievers (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Percent of 10th graders high in depressive symptoms, by gender and achievement level (grades and college plans), Monitoring the Future Survey.3 The 2020 data was collected in early 2020, just before COVID-19 shut schools down.

In addition, depressive symptoms increase among higher- AND lower-achieving teens, not just higher-achieving teens. The relative increase is a little larger among higher-achievers (depression rates triple from 2010 to 2021 among higher-achieving girls and double among lower-achieving girls), but that’s because the starting point in 2010 is so much lower among high-achieving girls. But in terms of the numbers of people, the largest increase is among lower-achieving girls. By 2021, a shocking 47% of lower-achieving 10th-grade girls had high rates of depressive symptoms. If we had to choose a group to worry about the most from this graph, it would be lower-achieving girls. Perhaps not coincidentally, lower-achieving girls also spend the most time on social media: 42% report spending 5 or more hours a day on social media, compared to 27% of higher-achieving girls in 10th grade.

Conclusions

Overall, this data from nationally representative samples of U.S. teens over three decades provides direct evidence against the academic pressure hypothesis. Teens are not spending more time on homework, they are not reporting more competition for grades, and depression rates are increasing among both lower and higher-achieving teens, with lower-achieving girls showing the highest depression rates.

There are some other datasets that show some evidence of increased academic pressure or links between mental distress and school. The Health Behaviors of School-Aged Children study, which mostly surveys teens in Europe, shows increases in schoolwork pressure since 2010. Suicides in teens tend to peak during the school year and go down during the summer (though this pattern could be due to bullying, lack of sleep from early school start times, and other factors unconnected to academic pressure). Some have argued that the lower life satisfaction of teens in higher-income countries is due to higher “learning intensity.” Still, the onus is on the proponents of the academic pressure hypothesis to prove their case that there was a sharp increase in academic pressure around 2012, especially with U.S. data.

Of course, many factors can cause depression, and academic pressure may certainly be the cause of some cases. But we’re not trying to explain all cases of depression; we’re trying to explain why teen depression increased so much after 2012. Given that homework time has declined (and was never high to begin with compared to screen media time), given that teen-reported academic pressure has primarily declined over this time, and that teens under more academic pressure are actually less likely to be depressed, the evidence I’m able to find in the Monitoring the Future study contradicts the academic pressure hypothesis.

That leaves us back where we started: The main suspect in the teen mental illness epidemic is still smartphones and social media. Unlike homework time and academic pressure, time spent online and on social media increased enormously while teen depression (and loneliness) was rising, and experimental evidence points to a causal role for social media use on teen depression, as Jon showed in a previous post. Averaging across 2018-2021 in Monitoring the Future, 22% of 10th-grade girls said they spent seven or more hours a day using social media. How can that not have a significant impact?

Derek Thompson’s story in the Atlantic ends with a quote from psychologist Laurence Steinberg: “Sometimes I just think, my God,” he says about the academic pressure teens face today, “Like, shouldn’t we care about giving kids a good experience of being a kid?”

Yes, we should – and that means making sure kids aren’t getting sucked into an addictive activity, giving their lives away to social media companies and becoming depressed because of it. Kids should be out socializing a lot more. Social media is one of the main reasons they are doing less of that than ever.

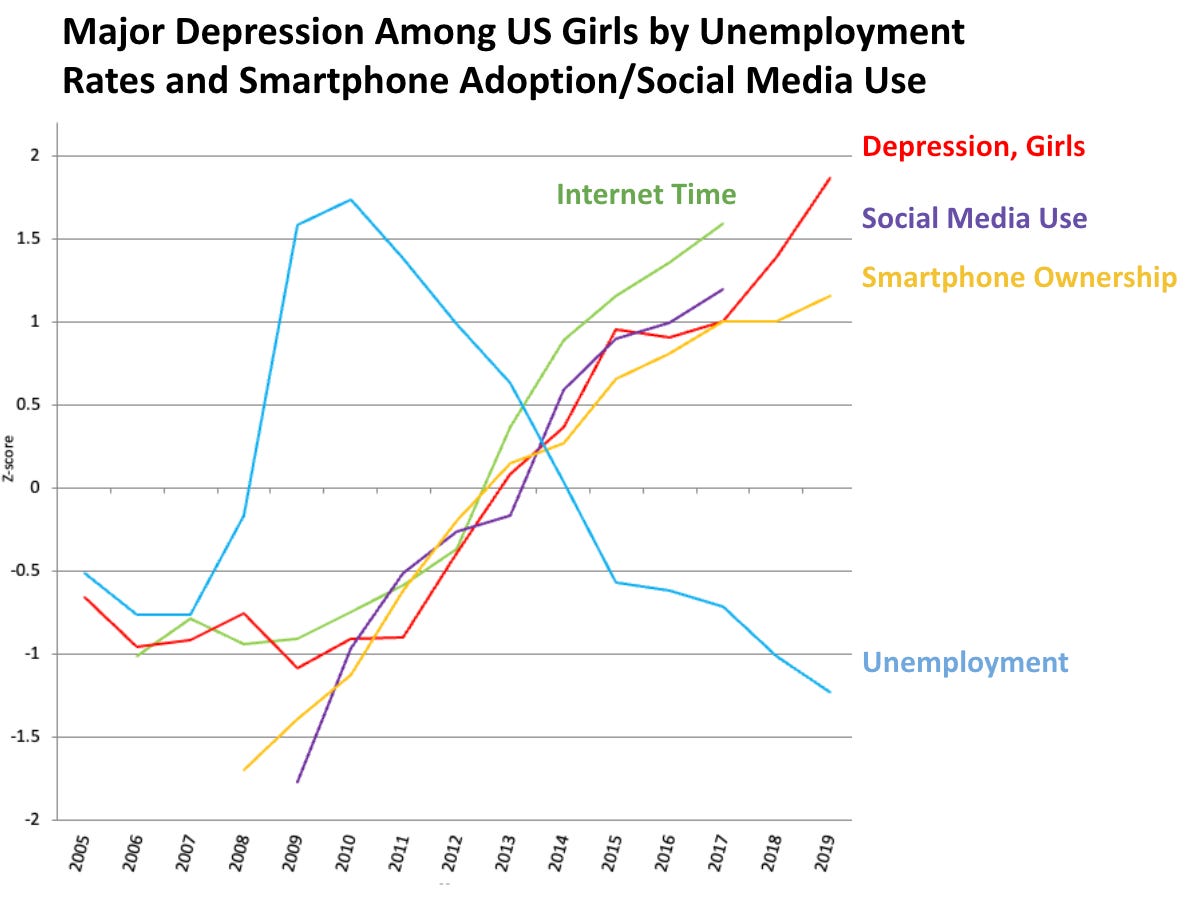

Teen depression rose after 2012 when the U.S. economy was finally improving after the Great Recession – precisely the opposite of what you’d expect if depression was due to poor economic times. For example, here’s unemployment vs. teen girls’ depression from Generations also showing internet time and smartphone adoption lining up with depression:

Figure. Major depression among US teen girls correlates with technology use, not with the unemployment rate, 2005-2019

NOTES: Standardized to Z-scores to be shown on the same graph. Internet use among 8th and 10th graders, major depressive episode in the last year among 12- to 17-year-old girls, social media use among 8th and 10th graders, smartphone ownership among adults, and the U.S. national unemployment rate. From Chapter 6, Generations.

The declines in homework time since 2012 are larger among White and higher socioeconomic status (SES) teens than among Black and Hispanic and lower socioeconomic status teens. For example, time spent doing homework declined by 9 minutes a day from 2012 to 2021 among higher SES 8th graders but by only 2 minutes among lower SES 8th graders. Homework time declined by 8 minutes among White 8th graders but by 3 minutes among Black and Hispanic 8th graders. Both of these trends could be interpreted as counterpoints to the idea that privileged teens are grappling with increasing academic pressure.

Depressive symptoms are measured by a 6-question scale. The 6 questions are: “Life often seems meaningless,” “I enjoy life as much as anyone” (reverse scored), “The future often seems hopeless,” “I feel that I can’t do anything right,” “I feel that my life is not very useful,” and “It feels good to be alive” (reverse scored). Response choices ranged from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). An average item score (all 6 responses averaged) of 3 or more is considered high. Sample sizes were smaller in 2020 because data collection was interrupted by Covid. On this graph, years are merged into pairs to keep sample sizes high at each point on the graph. Data for boys and girls are shown separately, given that the mental health trends are often more pronounced for girls and because there are more girls than boys in the high-achiever group.

https://jimgeschke.substack.com/p/we-need-a-12-step-program-for-cellphone

I'm a retired teacher (ret. Dec. 2018). I saw the same trend in my final years of teaching. I was competing for their most precious classroom asset -- their attention.

My competition? The high IQ's and salaries of brilliant app developers in Silicon Valley and elsewhere. And I was losing. Badly. I wrote about it in one of my first pieces on Substack about 18 months ago (see link above). I concluded we need a 12-Step program for phone addiction. The first people who should do the 12-Step ... the parents.

First, the academic pressure assertion is more dangerous thinking that contributes to unpreparedness for adulthood. What an insidiously infantilizing assertion! Of course being overwhelmed and overworked can make one depressed, but there’s a goal in this case, and pressure can be very useful towards getting there. Making too much of pressure is only going to discourage teens from rising to the occasion.

This insidious line of thought correlates to what on social media is destroying young minds. Catastrophic ideation. All men are rapists. White people are evil oppressors. The planet is dying. Being female is a lifetime of trauma. If grabbed by a guy you should be traumatized for life....on and on and on. These ideas are CRUEL and peddled by useful idiot teachers....not just social media, often feminist unmarried childless teachers ironically living their best life while destroying the minds of our youth.